|

EXECUTIVE

DEPARTMENT,

Frankfort, Ky., December 28, 1860.

Hon.

S. F. HALE,

Commissioner from the State of Alabama:

Your

communication of the 27th instant, addressed to

me by authority of the State of Alabama, has been attentively

read. I concur with you in the opinion that the grave political

issues yet pending and undetermined between the slave-holding and

non-slave-holding States of the Confederacy are of a character to

render eminently proper and highly important a full and frank

conference on the part of the Southern members, identified, as

they undoubtedly are, by a common interest, bound together by

mutual sympathies, and with the whole social fabric resting on

homogeneous institutions. And coming as you do in a spirit of

fraternity, by virtue of a commission from a sister Southern

State, to confer with the authorities of this State in reference

to the measures necessary to be adopted to protect the interests

and maintain the honor and safety of the States and their

citizens, I extend you a cordial welcome to Kentucky.

You

have not exaggerated the grievous wrongs,

injuries, and indignities to which the slave-holding States and

their citizens have long submitted with a degree of patience and

forbearance justly attributable alone to that elevated patriotism

and devotion to the Union which would lead them to sacrifice

well-nigh all save honor to recover the Government to its

original integrity of administration and perpetuate the Union

upon the basis of equality established by the founders of the

Republic. I may even add that the people of Kentucky, by reason

of their geographical position and nearer proximity to those who

seem so madly bent upon the destruction of our constitutional

guarantees, realize yet more fully than our friends farther south

the intolerable wrongs and menacing dangers you have so

elaborately recounted. Nor are you, in my opinion, more keenly

alive than are the people of this State to the importance of

arresting the insane crusade so long waged against our

institutions and our society by measures which shall be certainly

effective. The rights of African slavery in the United States and

the relations of the Federal Government to it, as an institution

in the States and Territories, most assuredly demand at this time

explicit definition and final recognition by the North. The

slave-holding States are now impelled by the very highest law of

self-preservation to demand that this settlement should be

concluded upon such a basis as shall not only conserve the

institution in localities where it is now recognized, but secure

its expansion, under no other restrictions than those which the

laws of nature may throw around it. That unnecessary conflict

between free labor and slave labor, but recently inaugurated by

the Republican party as an element in our political struggles,

must end, and the influence of soil, of climate, and local

interests left unaided and unrestricted save by constitutional

limitations to control the extension of slavery over the public

domain. The war upon our social institutions and their guaranteed

immunities waged through the Northern press, religious and

secular, and now threatened to be conducted by a dominant

political organization through the agency of State Legislatures

and the Federal Government must be ended. Our safety, our honor,

and our self-preservation alike demand that our interests be

placed beyond the reach of further assault.

The

people of Kentucky may differ variously touching

the nature and theory of our complex system of government, but

when called upon to pass upon these questions at the polls I

think such an expression would develop no material variance of

sentiment touching the wrongs you recite and the necessity of

their prompt adjustment. They fully realize the fatal result of

longer forbearance, and appreciate the peril of submission at

this juncture. Kentucky would leave no effort untried to preserve

the union of the States upon the basis of the Constitution as we

construe it, but Kentucky will never submit to wrong and

dishonor, let resistance cost what it may. Unqualified

acquiescence in the administration of the Government upon the

Chicago platform, in view of the movements already inaugurated at

the South and the avowed purposes of the representative men of

the Republican party, would, I feel assured, receive no favor in

this State. Whether her citizens shall, in the last resort, throw

themselves upon the right of revolution as the inherent right of

a free people never surrendered, or shall assert the doctrine of

secession, can be of little practical import. When the time of

action comes (and it is now fearfully near at hand) our people

will be found rallied as a unit under the flag of resistance to

intolerable wrong, and being thus consolidated in feeling and

action, I may well forego any discussion of the abstract theories

to which one party or another may hold to cover their resistance.

It

is true that as sovereign political communities the

States must determine, each for itself, the grave issues now

presented; and it may be that, when driven to the dire extremity

of severing their relations with the Federal Government, formal,

independent, separate State action will be proper and necessary.

But resting, as do these political communities, upon a common

social organization, constituting the sole object of attack and

invasion, confronted by a common enemy, encompassed by a common

peril--in a word, involved in one common cause, it does seem to

me that the mode and manner of defense and redress should be

determined in a full and free conference of all the Southern

States, and that their mutual safety requires full co-oper-ation

in carrying out the measures there agreed upon. The source whence

oppression is now to be apprehended is an organized power, a

political government in operation, to which resistance, though

ultimately successful (and I do not for a moment question the

issue), might be costly and destructive. We should look these

facts in she face, nor close our eyes to what we may reasonably

expect to encounter. I have therefore thought that a due regard

to the opinions of all the slave-holding States would require

that those measures which concern all alike and must ultimately

involve all should be agreed upon in common convention and

sustained by united action.

I

have before expressed the belief and confidence, and

do not now totally yield the hope, that if such a convention of

delegates from the slave-holding States be assembled, and, after

calm deliberation, present to the political party now holding the

dominance of power in the Northern States and soon to assume the

reins of national power, the firm alternative of ample guarantees

to all our rights and security for future immunity or resistance,

our just demands would be conceded and the Union be perpetuated

stronger than before. Such an issue, so presented to the Congress

of the United States and to the Legislatures and people of the

Northern States (and it is practicable, in abundant time before

the Government has passed into other hands) would come with a

moral force which, if not potent to control the votes of the

representative men, might produce a voice from their constituents

which would influence them. But if it fail, our cause would

emerge, if possible, stronger fortified by the approbation of the

whole conservative sentiment of the country and supported by a

host of Northern friends who would prove, in the ultimate issue,

most valuable allies. After such an effort every man in the

slave-holding States would feel satisfied that all had been done

which could be done to preserve the legacy bequeathed us by the

patriots of '76 and the statesmen of '89, and the South would

stand in solid, unbroken phalanx a unit. In the brief time left

it seems to me impracticable to effect this object through the

agency of commissioners sent to the different States. A

convention of authorized delegates is the true mode of bringing

about co-operation among the Southern States, and to that

movement I would respectfully ask your attention, and through you

solicit the co-operation of Alabama.

There

is yet another subject upon which the very highest

considerations appeal for a united Southern expression. On the

4th of March next the Federal Government, unless contingencies

now unlooked for occur, will pass into the control of the

Republican party. So far as the policy of the incoming

administration is foreshadowed in the antecedents of the

President elect, in the enunciations of its representative men

and the avowals of the press, it will be to ignore the acts of

sovereignty thus proclaimed by Southern States, and of coercing

the continuance of the Union. Its inevitable result will be civil

war of the most fearful and revolting character. Now, however the

people of the South may differ as to the mode and measure of

redress, I take it that the fifteen slave holding States are

united in opposition to such a policy, and would stand in solid

column to resist the application of force by the Federal

authority to coerce the seceding States. But it is of the utmost

importance that before such a policy is attempted to be

inaugurated the voice of the South should be heard in potential,

official, and united protest. Possibly the incoming

Administration would not be so dead to reason as after such an

expression to persist in throwing the country into civil war, and

we may therefore avert the calamity. An attempt "to enforce

the laws" by blockading two or three Southern States would

be regarded as quite a different affair from a declaration of war

against 13,000,000 of freemen; and if Mr. Lincoln and his

advisers be made to realize that such would be the issue of the

"force policy," it will be abandoned. Should we not

realize to our enemies that consequence and avert the disastrous

results? But if our enemies be crazed by victory and power and

madly persist in their purpose, the South will be better prepared

to resist.

You

ask the co-operation of the Southern States in

order to redress our wrongs. So do we. You have no hope of a

redress in the Union. We yet look hopefully to assurances that a

powerful reaction is going on at the North. You seek a remedy in

secession from the Union. We wish the united action of the slave

States, assembled in convention within the Union. You would act

separately; we unitedly. If Alabama and the other slave States

would meet us in convention, say at Nashville or elsewhere, as

early as the 5th day of February, I do not doubt shall we would

agree in forty-eight hours upon such reasonable guarantees, by

way of amendment to the Constitution of the United States, as

would command at least the approbation of our numerous friends in

the free States, and by giving them time to make the question

with the people there, such a reaction in public opinion might

yet take place as to secure us our rights and save the

Government. If the effort failed the South would be united to a

man, the North divided, the horrors of civil war would be averted

(if anything can avert the calamity). And if that be not possible

we would be in a better position to meet the dreadful collision.

By such action, too, if it failed to preserve the Government, the

basis of another confederacy would have been agreed upon, and the

new government would in this mode be launched into operation much

more speedily and easily than by the action you propose.

In

addition to the foregoing, I have the honor to

refer you to my letter of the 16th ultimo to the editor of The

Yeoman and to my letter to the Governors of the slave States,

dated the 9th of December, herewith transmitted to you, which,

together with what I have said in this communication, embodies,

with all due deference to the opinions of others, in my judgment,

the principles, policy, and position which the slave States ought

to maintain. The Legislature of Kentucky will assemble on the

17th of January, when the sentiment of the State will doubtless

find official expression. Meantime, if the action of Alabama

shall be arrested until the conference she has sought can be

concluded by communication with that department of the

government, I shall be pleased to transmit to the Legislature

your views. I regret to have seen in the recent messages of two

or three of our Southern sister States a recommendation of the

passage of laws prohibiting the purchase by the citizens of those

States of the slaves of the border slave-holding States. Such a

course is not only liable to the objection so often urged by us

against the abolitionists of the North of an endeavor to prohibit

the slave-trade between the States, but it is likewise wanting in

that fraternal feeling which should be common to States which are

identified in their institutions and interests. It affords me

pleasure, however, to add, as an act of justice to your State,

that I have seen no indication of such a purpose on the part of

Alabama. It would certainly be considered an act of in justice

for the border slave-holding States to prohibit, by their

legislation, the purchase of the products of the cotton-growing

States, even though it be founded upon the mistaken policy of

protection to their own interests. I cannot close this

correspondence without again expressing to you my gratification

in receiving you as the honored commissioner from your proud and

chivalrous State, and at your courteous, able, dignified, and

manly bearing in discharging the solemn and important duties

which have been assigned to you.

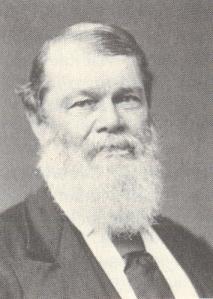

I

have the honor to be, with sentiments of high

consideration, your friend and obedient servant,

B.

MAGOFFIN.

|