|

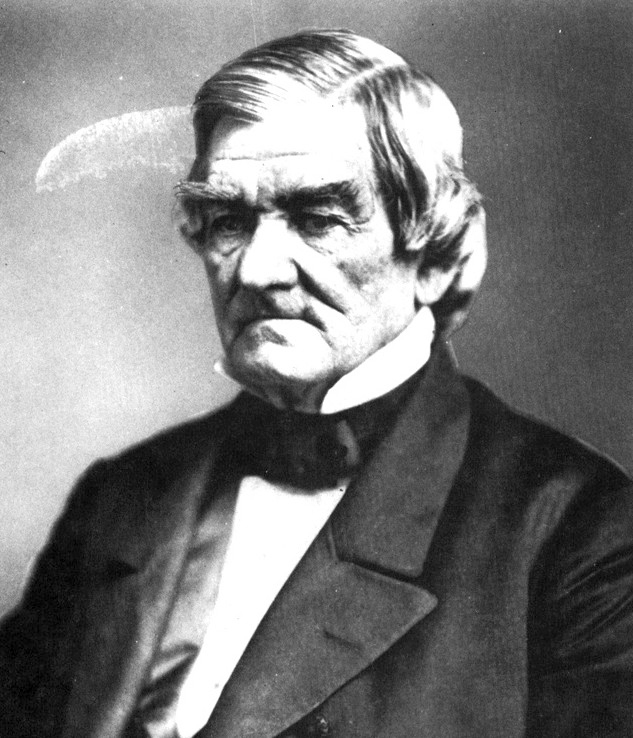

| John Ross, Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation |

Declaration by the People of the Cherokee Nation of the Causes Which

Have Impelled them to Unite Their Fortunes With Those of the

Confederate States of America.

October 28, 1861

| The story of the Indian nations in the Civil War is beyond the scope of this website, and, frankly, the publisher's knowledge. There is reason to believe that Chief Ross sided with the Confederates reluctantly. I would like to learn more about this in order to make this document more comprehensible to the reader. |

|

|

When circumstances beyond their control compel one people to sever the ties which have long existed between them and another state or confederacy, and to contract new alliances and establish new relations for the security of their rights and liberties, it is fit that they should publicly declare the reasons by which their action is justified. The

Cherokee people had

its origin in the South; its institutions are

similar to those of the

Southern States, and their interests identical

with theirs. Long since

it accepted the protection of the United

States of America,

contracted with them treaties of alliance and

friendship, and allowed

themselves to be to a great extent governed by their laws.

In

peace and war, they

have been faithful to their engagements with

the United States. With

much hardship and injustice to complain of,

they resorted to no other

means than solicitation and argument to

obtain redress. Loyal and

obedient to the laws and the stipulations of

the treaties, they served

under the flag of the United States, shared

the common dangers, and

were entitled to a share in the common glory,

to gain which their blood

was freely shed on the battlefield.

When

the dissensions

between the Southern and Northern States

culminated in a

separation of State after State from the Union, they

watched the progress of

events with anxiety and consternation. While

their institutions and

the contiguity of their territory to the states

of Arkansas, Texas and

Missouri made the cause of the seceding States

necessarily their own

cause, their treaties had been made with the

United States, and they

felt the utmost reluctance even in appearance

to violate their

engagements or set at naught the obligations of good

faith.

Conscious that they were a people few in numbers compared with either of the contending parties, and that their country might with no considerable force be easily overrun and devastated and desolation and ruin be the result if they took up arms for either side, their authorities determined that no other course was consistent with the dictates of prudence or could secure the safety of their people and immunity from the horrors of a war waged by an invading enemy than a strict neutrality, and in this decision they were sustained by a majority of the Nation. That

policy was

accordingly adopted and faithfully adhered to. Early

in the month of June of

the present year the authorities of the Nation

declined to enter into

negotiations for an alliance with the

Confederate States, and

protested against the occupation of the

Cherokee country by their

troops, or any other violation of their

neutrality. No act was

allowed that could be construed by the United

States to be a violation

of the faith of treaties.

But

Providence rules the

destinies of nations, and events, by

inexorable necessity,

overrule human resolutions. The number of the

Confederate States

increased to eleven, and their government is firmly

established and

consolidated. Maintaining in the field an army of two

hundred thousand men, the

war became for them but a succession of

victories. Disclaiming

any intention to invade the Northern States,

they sought only to repel

invaders from their own soil and to secure

the right of governing

themselves.

They

claimed only the

privilege asserted by the Declaration of

American Independence,

and on which the right of the Northern States

themselves to

self-government is formed, of altering their form of

government when it became

no longer tolerable and establishing new

forms for the security of

their liberties.

Throughout

the

Confederate States, we saw this great revolution

effected without violence

or suspension of the laws or the closing of

the courts, The military

power was nowhere placed above the civil

authorities. None were

seized and imprisoned at the mandate of

arbitrary power. All

division among the people disappeared, and the

determination became

unanimous that there should never again be any

union with the Northern

States. Almost as one man, all who were able

to bear arms rushed to

the defense of an invaded country, and nowhere

has it been found

necessary to compel men TO SERVE, or to enlist

mercenaries by the offer

of extraordinary bounties.

But,

in the Northern

States, the Cherokee people saw with alarm a

violated constitution,

all civil liberty put in peril, and all rules

of civilized warfare and

the dictates of common humanity and decency

unhesitatingly

disregarded. In states which still adhered to the

Union, a military

despotism had displaced the civil power and the laws

became silent amid arms.

Free speech and almost free thought became a

crime. The right of the

writ of habeas corpus, guaranteed by the

constitution, disappeared

at the nod of a Secretary of State or a

general of the lowest

grade. The mandate of the Chief Justice of the

Supreme Court was at

naught by the military power, and this outrage on

common right, approved by

a President sworn to support the

constitution. War on the

largest scale was waged, and the immense

bodies of troops called

into the field in the absence of any law

warranting it under the

pretense of suppressing unlawful combination

of men.

The

humanities of war,

which even barbarians respect, were no longer

thought worthy to be

observed. Foreign mercenaries and the scum of the

cities and the inmates of

prisons were enlisted and organized into

brigades and sent into

Southern States to aid in subjugating a people

struggling for freedom,

to burn, to plunder, and to commit the basest

of outrages on the women.

While the heels of armed tyranny trod upon

the necks of Maryland and

Missouri, and men of the highest character

and position were

incarcerated upon suspicion and without process of

law, in jails, in forts,

and prison ships, and even women were

imprisoned by the

arbitrary order of a President and Cabinet

Ministers; while the

press ceased to be free, and the publication of

newspapers was suspended

and their issues seized and destroyed. The

officers and men taken

prisoners in the battles were allowed to remain

in captivity by the

refusal of the Government to consent to an

exchange of prisoners; as

they had left their dead on more than one

field of battle that had

witnessed their defeat, to be buried and

their wounded to be cared

for by southern hands.

Whatever

causes the

Cherokee people may have had in the past to

complain of some of the

Southern states, they cannot but feel that

their interests and

destiny are inseparably connected with those of

the south. The war now

waging, is a war of Northern cupidity and

fanaticism against the

institution of African servitude; against the

commercial freedom of the

South, and against the political freedom of

the states, and its

objects are to annihilate the sovereignty of those states and utterly

change

the nature of the general government.

The Cherokee people and their neighbors were warned before the war commenced that the first object of the party which now holds the powers of government of the United States would be to annul the institution of slavery in the whole Indian country and make it what they term free territory and after a time a free state; and they have been also warned by the fate which has befallen those of their race in Kansas, Nebraska and Oregon that at no distant day they too would be compelled to surrender their country at the demand of Northern rapacity, and be content with an extinct nationality, and with reserves of limited extent for individuals, of which their people would soon be despoiled by speculators, if not plundered unscrupulously by the state. Urged by these considerations, the .Cherokees, long divided in opinion. became unanimous, and like their brethren, the Creeks, Seminoles, Choctaws, and Chickasaws, determined, by the undivided voice of a General Convention of all the people, held at Tahlequah on the twenty-first day of August, in the present year, to make common cause with the South and share its fortunes. In now, carrying this resolution into effect and consummating a treaty of alliance and friendship with the Confederate States of America, the Cherokee people declare that they have been faithful and loyal to their engagements with the United States until, by placing their safety and even their national existence in eminent peril, those States have released them from those engagements. Menaced by a great danger, they exercise the inalienable right of self defense, and declare themselves a free people, independent of the Northern States of America, and at war with them by their own act. Obeying the dictates of prudence and providing for the general safety and welfare, confident of the rectitude of their intentions and true to the obligations of duty and honor, they accept the issue thus forced upon them, unite their fortunes now and forever with those of the Confederate States, and take up arms for the common cause, and with entire confidence in the justice of that cause and with a firm reliance upon Divine Providence, will resolutely abide the consequences.

JOSHUA ROSS, Clerk National Committee. THOMAS PEGG, President of National Committee. LACEY MOUSE, Speaker of Council. THOMAS B. WOLF, Clerk of Council. Approved. JOHN ROSS, Principal Chief |

Back to Causes of the Civil War (Main page) Back to State and Local Resolutions and Correspondence Source: Official Records of the War of the Rebellion, xxxxxx, p. 503. Date added to website: June 13, 2023 |