|

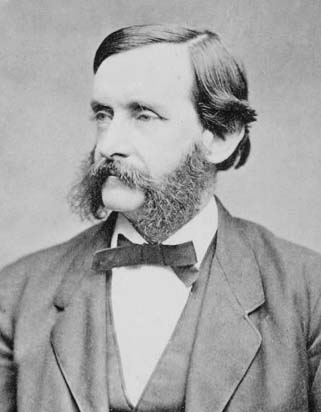

| Thomas

Wentworth Higginson |

MASSACHUSETTS IN

MOURNING.

A

SERMON,

PREACHED

IN WORCESTER, ON

SUNDAY, JUNE 4, 1854.

BY

THOMAS WENTWORTH

HIGGINSON,

Minister of the

Worcester Free Church.

| Thomas

Wentworth Higginson (1823--1911) was a Massachusetts pastor, statesman,

soldier, and writer. He was very active in the anti-slavery

movement, going so far as to serve as an officer in the 1st South

Carolina Volunteers, a regiment formed from freed slaves along the

South Carolina coast. In the antebellum period he was a Unitarian

pastor at the Worcestor Free Church, and actively tried to free Anthony

Burns, an escaped slave who had been captured in Boston and was

eventually returned to slavery in Virginia under the Fugitive Slave

Act. This sermon was delivered on Sunday, June 4, 1854, in

response to the events surrounding the capture and re-enslavement of

Burns. Higginson was also one of the "Secret Six" who supported

John Brown's Harpers Ferry raid in October, 1859. Unlike the

others, he did not flee the country to escape the consequences of his

acts. |

|

|||

|

You

have imagined my subject

beforehand, for there is but one subject on which I could preach, or

you could

listen, today. Yet, how hard it is to

say one word of that. You do not ask, at

a funeral, that the bereaved mourners themselves should speak, but you

call in

one a little farther removed, to utter words of comfort, if comfort

there be. But to-day is, or should be, to

every

congregation in Massachusetts, a day of funeral service—we are all

mourners—and

what is there for me to say? Yet,

even in this gloom, the

faculty of wonder is left; as at funerals, men ask in a low tone,

around the

coffin, what was the disease that smote this fair form, and are we safe

from

the infection? So we now ask, what is

lost, and how have we lost it, and what have we left?

Is it all gone (men say), that old New

England heroism and enthusiasm? Is there

any disinterested love of Freedom left in Massachusetts?

And then they think with joy (as I do), that,

at least, Freedom did not die without a struggle, and that it took

thousands of

armed men to lay her in the grave at last. I

am thankful for all this. Words are

nothing—we have been surfeited with

words for twenty years. I am thankful

that this time there was action also ready for Freedom.

God gave men bodies, to live and work in; the

powers of those bodies are the first things to be consecrated to the

Right. He gave us higher powers, also, for

weapons,

but, in using those, we must not forget to hold the lower ones also

ready; else

we miss our proper manly life on earth, and lay down our means of

usefulness

before we have outgrown them. “Render

unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s and unto God the things which

are

God's.” Our souls and bodies are both God’s, and resistance to tyrants

is

obedience to Him. If

you meet men whose souls are

contaminated, and have time enough to work on them, you can deal with

them by

the weapons of the soul alone; but if men array brute force against

Freedom—pistols,

clubs, drilled soldiers, and stone walls—then the body also has its

part to do

in resistance. You must hold yourself

above men, I own, yet not too far above to reach them.

I

do not like even to think of

taking life, only of giving it; but physical force that is forcible

enough,

acts without bloodshed. They say that

with twenty more men at hand, that Friday night, at the Boston Court

House, the

Slave might have been rescued without even the death of that one man

who was

perhaps killed by his frightened companions, then and there. So you see force may not mean bloodshed; and

calm, irresistible force, in a good cause, becomes sublime. The strokes on the door of that Court House

that night for instance—they may perchance have disturbed some dreamy

saint

from his meditations, (if dreamy saints abound in Court Square)—but I

think

they went echoing from town to town, from Boston to far New Orleans,

like the

first drum beat of the Revolution—and each reverberating throb was a

blow upon

the door of every Slave-prison of this guilty Republic.

That

first faint throb of Liberty

was a proud thing for Boston; Boston, which was a scene so funereal a

week

after. Men say the act of one Friday

helped prepare for the next; I am glad if it did. If

the attack on the Court House had no

greater effect than to send that Slave away under a guard of two

thousand men,

instead of two hundred, it was worth a dozen lives.

If we are all Slaves indeed if there is no

law in Massachusetts except the telegraphic orders from Washington—if

our own

military are to be made Slave-catchers if our Governor is a mere piece

of State

ceremony, permitted only to rise at a military dinner and thank his own

soldiers for their readiness to shoot down his own constituents,

without even

the delay of a riot act—if Massachusetts is merely a conquered province

and

under martial law—then I wish to know it, and I am grateful for

every

additional gun and sabre that forces the truth deeper into our hearts. Lower, Massachusetts, lower, kneel still

lower! Serve, Irish Marines! the

kidnappers, your masters; down in the dust, citizen soldiery! before

the Irish

Marines, and for you, O Governor, a lower humility yet, and your homage

must be

paid, at second hand, before the stained and soiled “citizen soldiery.”

I

remember the great

trades-procession in Boston, a few years since, in honor of the

visitors from

the North, from the free soil of Canada. Then

all choice implements, which Massachusetts had

invented to supply

the industry of the world, were brought forth for exhibition, and

superb was

the show. This time we had visitors from

the South—the South which uses tools also—and imports them all, “hoes,

spades,

axes, politicians, and ministers.” So

the last new implements for her use, were to be exhibited now. There were twenty one specimens of Boston

military companies. There were the two

hundred more confidential bullies, for whom the city was ransacked, men

so

vile, that it was said the police had no duties left, for all the

dangerous

persons were employed as policemen themselves, men whom a Police Judge

having

inspected, recognized criminal after criminal, who had been sentenced

by

himself to the House of Correction; these came next.

Truly as there is joy in heaven over one

sinner who repenteth, so there was joy in Boston that day, over one

sinner who

had not repented—over every man in whom the powers of hell were strong

enough,

aided by public brandy, to fit him for that terrible service. Those were the tools marshalled forth for

exhibition. But why were these only

shown? Why were the finer, the more

precious implements kept invisible that day, the real engines of that

Slaveholder’s triumph? Why not make the

picture perfect? Place, O Chief Marshal,

between the Slave and the guardian cannon, the crowning glory of that

sad

procession, the Slaveholder in his carriage, and chain, on the one

side, the

Mayor of Boston, and, on the other side, the Governor of the

Commonwealth, with

the motto, “The Representative Men of Massachusetts, These tools

she gives,

Virginia, to thee!” I

mean no personality. The men who occupy

these offices, are men who

(I have always thought) did them honor. I

suppose that neither would own a Slave, nor (personally) catch one. No doubt they favorably represent the average

of Massachusetts men. But I introduce

them for precisely this reason, to show the tragedy of our American

institutions, that they take average Massachusetts men, put them into

public

office, and then, demanding more of them than their education gives

them

manliness to meet—use them, crush them, and drop them, into the

dishonor with which

these hitherto honored men are suddenly overwhelmed to-day. If

such be the influence of our

national organization, what good do our efforts do?

Our labor to reform the North, with the whole

force of nationalized Slavery to resist, is like the effort of Sir John

Franklin, on his first voyage, to get northward by travelling on the

ice. He travelled toward the pole for six

weeks,

no doubt of that; but at the end of the time he was two hundred miles

farther

from it than when he started. The ice

had floated southward—and our ice floats southward also.

And so it will be, while this Union

concentrates power in the hands of Slaveholders, and gives the North

only

commercial prosperity, the more thoroughly to enervate and destroy it. Here,

for instance, is the

Nebraska Emigration Society; it is indeed, a noble enterprise, and I am

proud

that it owes its origin to a Worcester man but where is the good of

emigrating

to Nebraska, if Nebraska is to be only a transplanted Massachusetts,

and the

original Massachusetts has been tried and found wanting?

Will the stream rise higher than its source?

Settle your Nebraska ten years, and you will

have your New England harvest of corn and grain, more luxuriant in that

virgin

soil—ah, but will not the other Massachusetts crop come also, of

political

demagogues and wire-pullers, and a sectarian religion, which will

insure the

passage of the greatest hypocrite to heaven, if he will join the right

church

before he goes? And give the emigrants

twenty years more of prosperity, and then ask them, if you dare, to

break law

and disturb order, and risk life, merely to save their State from the

shame

that has just blighted Massachusetts? In

view of these facts, what

stands between us and a military despotism? “Sure

guarantees,” you say. So

has every nation thought until its fall came. “The

outward form of Roman institutions stood uninjured

till long after

Caligula had made his horse consul.” What

is your safeguard? Nothing but a parchment

Constitution, which

has been riddled through and through whenever it pleased the Slave

Power; which

has not been able to preserve to you the oldest privileges of

Freedom—Habeas

Corpus and Trial by Jury! Stranger

still, that men should think to find a security in our material

prosperity, and

our career of foreign conquest, and our acquisition of gold mines, and

forget

that these have been precisely the symptoms which have prophesied the

decline

of every powerful commercial state—Rome, Carthage, Tyre, Venice, Spain,

Holland, and all the rest. In

the third century after the

birth of Jesus, Terullian painted that brilliant picture of the Roman

power,

which describes us, as if it were written for us: “Certainly,”

says he, “the world

becomes more and more our tributary; none of its secret recesses have

remained

inaccessible, all are known, frequented, and all have become the scene

or the

object of traffic. Who now dreads an

unknown island? who trembles at a reef? our ships are sure to be met with

everywhere—everywhere

is a people, a state; everywhere is life. We

crush the world beneath our weight—onerosi sumus

mundo.” And

Rome perished, almost when the words were uttered! How

simple the acts of our

tragedy may be! Let another Fugitive Slave case occur, and more blood

be spilt

(as might happen another time)—let Massachusetts be declared

insurrectionary,

and placed under martial law, (as it might)—let the President be made

Dictator,

with absolute power; let him send his willing Attorney General to buy

up

officers of militia (which would be easy), and frighten Officers of

State

(which would be easier)—let him get half the press, and a quarter of

the

pulpits, to sustain his usurpation, under the name of “law and order”

—let the

flame spread from New England to New York, from New York to Ohio, from

Ohio to

Wisconsin —and how long would it take for some future Franklin Pierce

to stand

where Louis Napoleon stands now? How

much would the commercial leaders of the East resist, if an appeal were

skillfully

made to their pockets?—or the political demagogues of the West, if an

appeal

were made to their ambition? It seems

inconceivable! Certainly—so did the coup

d'etat of Louis Napoleon, the day before it happened! “Do

not despair of the Republic,”

says someone, remembering the hopeful old Roman motto.

But they had to despair of that one in the

end—and why not of this one also? Why,

when we were going on, step by step, as older Republics have done,

should we

expect to stop just as we reach the brink of Niagara?

The love of Liberty grows stronger every

year, some think, in some places. Thirty

years ago, it cost only $25 to restore a Fugitive Slave from Boston,

and now it

costs $100,000—but still the Slave is restored.

I know there are thousands of hearts which

stand pledged to Liberty now, and these may save the State, in spite of

her

officials and her military; but can they save the Nation?

They may give us disunion instead of

despotism, but can they give us anything better? Can

they even give us anything so good? We

talk of the Anti-Slavery sentiment as

being stronger; but in spite of your Free Soil votes, your Uncle Tom's

Cabin,

and your New York Tribunes, here is the simple fact: the South

beats us more

and more easily every time. So

chess-players, when they have once or twice overcome a weak antagonist,

think

it safe, next time, to give up to him a half dozen pieces by way of

odds—and

after all gain the victory. Compare this

Nebraska game with the previous ones. The

Slave Power could afford to give us the Whig party on our side, this

time—could

give up to us the commercial influence of Boston and New York, so

strong an

ally before—it has not had the name and presence of Daniel Webster to

help it

now, nor the voices of clergymen, nor the terror of disunion, nor the

weariness

after a long Anti-Slavery excitement: it has dispensed with all

these—nay, the

whole contest was on our own soil, to defend the poor little landmark

we had

retreated to long before—and for all this, the Slave Power has

conquered us,

just as easily as it conquered us on Texas, Mexico, and the compromises

of 1850. No

wonder that this excitement is

turning Whigs and Democrats into Free Soilers, and Free Soilers into

disunionists. But this is only the eddy,

after all; the

main current sets the wrong way. The

nation

is intoxicated and depraved. It takes

all the things you count as influential—all the “spirit of the age,”

and the “moral

sentiment of Christendom,” and the best eloquence and literature of the

time—to

balance the demoralization of a single term of Presidential patronage. Give the offices of the nation to be

controlled by the Slave Power, and I tell you that there is not one in

ten,

even of professed Anti-Slavery men, who can stand the fire in that

furnace of

sin; and there is not a plot so wicked but it will have, like all its

predecessors, a sufficient majority when the time comes.

Do

you doubt this? Name, if you can, a

victory of Freedom, or a

defeat of the Slave Power, within twenty years, except on the right of

petition, and even that was only a recovery of lost ground. Do you say, the politicians are false, but

the people mark the men who betray them! True,

they mark them, but as merchants mark

goods, with the cost price, that they may raise the price a little,

when they

want to sell the same article again. You

must go back to the original Missouri Compromise, if you wish to prove

that

even Massachusetts punishes traitors to Freedom, by any severer penalty

than a

seat on her Supreme Bench. For myself, I

do not believe in these Anti-Slavery spasms of our people, for the same

reason

that Coleridge did not believe in ghosts, because I have seen too many

of them

myself. I remember when our

Massachusetts delegation in Congress, signed a sort of threat that the

State

would withdraw from the Union if Texas came in, but it never happened. I remember the State Convention at Faneuil

Hall in 1845, where the lion and the lamb lay down together, and George

T. Curtis

and John G. Whittier were Secretaries; and the Convention solemnly

pronounced

the annexation of Texas to be “the overthrow of the Constitution, the

bond of

the existing Union.” I remember how one

speaker boasted that if Texas was voted in by joint resolution, it

might be

voted out by the same. But somehow, we

have never mustered that amount of resolution; and when I hear of State

Street

petitioning for the repeal of its own Fugitive Slave Law, I remember

the lesson. For

myself, I do not expect to

live to see that law repealed by the votes of politicians at Washington. It can only be repealed by ourselves, upon

the soil of Massachusetts. For one, I am

glad to be deceived no longer. I am glad

of the discovery— (no hasty thing, but gradually dawning upon me for

ten years)

—that I live under a despotism. I have

lost the dream that ours is a land of peace and order.

I have looked thoroughly through our “Fourth

of July,” and seen its hollowness—and I advise you to petition your

City

Government to revoke their appropriation for its celebration (or give

the same

to the Nebraska Emigration Society), and only toll the bells in all the

churches, and hang the streets in black from end to end.

O shall we hold such ceremonies when only

some statesman is gone, and omit them over dead Freedom, whom all true

statesmen only live to serve! At

any rate my word of counsel to

you is to learn this lesson thoroughly—a revolution is begun!

not a

Reform, but a Revolution. If you take

part in politics henceforward, let it be only to bring nearer the

crisis which

will either save or sunder this nation—or perhaps save in sundering. I am not very hopeful, even as regards you; I

know the mass of men will not make great sacrifices for Freedom, but

there is

more need of those who will. I have lost

faith forever in numbers; I have faith only in the constancy and

courage of a “forlorn

hope.” And for aught we know, a case may

arise, this week, in Massachusetts, which may not end like the last one. Let

us speak the truth. Under the influence of

Slavery, we are

rapidly relapsing into that state of barbarism in which every man must

rely on

his own right hand for his protection. Let

any man yield to his instinct of Freedom, and resist oppression, and

his life

is at the mercy of the first drunken officer who orders his troops to

fire. For myself, existence looks worthless

under such circumstances; and I can only make life

worth living for, by becoming a revolutionist. The

saying seems dangerous; but why not say it if one

means it, as I

certainly do. I respect law and order,

but as the ancient Persian sage said, “always to obey the laws,

virtue

must relax much of her vigor.” I see, now, that while Slavery is

national, law

and order must constantly be on the wrong side. I

see that the case stands for me precisely as it stands

for Kossuth and

Mazzini, and I must take the consequences. Do

you say that ours is a

Democratic Government, and there is a more peaceable remedy? I deny that we live under a Democracy. It is an oligarchy of Slaveholders, and I

point to the history of a half century to prove it.

Do you say, that oligarchy will be

propitiated by submission? I deny it. It is the plea of the timid in all ages. Look at the experience of our own country. Which is most influential in Congress—South

Carolina, which never submitted to anything, or Massachusetts, with

thrice the

white population, but which always submits to everything?

I tell you, there is not a free State in the

Union which would dare treat a South Carolinian as that State treated

Mr. Hoar; or, if it had been done, the

Union

would have been divided years ago. The

way to make principles felt is to assert them—peaceably, if you can;

forcibly,

if you must. The way to promote Free

Soil is to have your own soil free; to leave courts to settle

constitutions,

and to fall back (for your own part) on first principles: then it will

be seen

that you mean something. How much free

territory is there beneath the Stars and Stripes? I

know of four places—Syracuse, Wilkes-Barre,

Milwaukie, and Chicago: I remember no others. “Worcester,”

you say. Worcester

has not yet been tried. If you think

Worcester County is free, say so and act accordingly.

Call a County Convention, and declare that

you leave legal quibbles to lawyers, and parties to politicians, and

plant

yourselves on the simple truth that God never made a Slave, and that

man shall

neither make nor take one here! Over

your own city, at least, you have power; but will you stand the test

when it

comes? Then do not try to avoid it. For one thing only I blush—that a Fugitive

has ever fled from here to Canada. Let

it not happen again, I charge you, if you are what you think you are. No longer conceal Fugitives and help them on,

but show them and defend them. Let the

Underground Railroad stop here! Say to

the South that Worcester, though a part of a Republic, shall be as free

as if

ruled by a Queen! Hear, O Richmond!

and give ear, O Carolina! henceforth Worcester is Canada to the Slave!

And what will Worcester be to the

kidnapper? I dare not tell; and I fear

that the poor

sinner himself, if once recognized in our streets, would scarcely get

back to

tell the tale. I

do not discourage more

peaceable instrumentalities; would to God that no other were ever

needful. Make laws, if you can, though you

have State

processes already, if you had officers to enforce them; and, indeed,

what can

any State process do, except to legalize nullification?

Use politics, if you can make them worth

using, though a coalition administration proved as powerless, in the

Sims case,

as a Whig administration has proved now. But

the disease lies deeper than these remedies can reach.

It is all idle to try to save men by law and

order, merely, while the men themselves grow selfish and timid, and are

only

ready to talk of Liberty, and risk nothing for it.

Our people have no active physical habits;

their intellects are sharpened, but their bodies, and even their

hearts, are

left untrained; they learn only (as a French satirist once said) the

fear of

God and the love of money; they are taught that they owe the world

nothing, but

that the world owes them a living, and so they make a living; but the

fresh,

strong spirit of Liberty droops and decays, and only makes a dying. I charge you, parents, do not be so easily

satisfied; encourage nobler instincts in your children, and appeal to

nobler

principles; teach your daughter that life is something more than dress

and

show, and your son that there is some nobler aim in existence than a

good

bargain, and a fast horse, and an oyster supper. Let

us have the brave, simple instincts of

Circassian mountaineers, without their ignorance; and the unfaltering

moral

courage of the Puritans, without their superstition; so that we may

show the

world that a community may be educated in brain without becoming

cowardly in

body; and that a people without a standing army may yet rise as one

man, when

Freedom needs defenders. May

God help us so to redeem this

oppressed and bleeding State, and to bring this people back to that

simple love

of Liberty, without which it must die amidst its luxuries, like the sad

nations

of the elder world. May we gain more

iron in our souls, and have it in the right place; have soft hearts and

hard

wills, not as now, soft wills and hard hearts. Then

will the iron break the Northern iron and the steel

no longer; and “God

save the Commonwealth of Massachusetts!” will be at last a hope

fulfilled. |

Back to Causes of the Civil War (Main page) Back to Sermons and Other Religious Tracts Source: The University of Michigan Libraries Date added to website: Oct 21, 2024 |