|

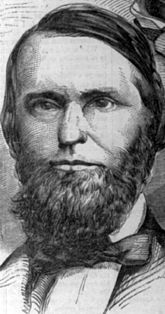

| William Waters Boyce |

|

A Letter in the Charleston Daily Courier

Aug. 8, 1860 |

| This

is an interesting letter. The author (William Waters Boyce,

1818--1890) was a minor South Carolina politician; in 1860 he was

serving in the U.S. House of Representatives, and he later served in

the Confederate Congress. This letter was written to two friends,

Provence and Lyles, and then published in the Southern Guardian,

a Columbia paper, and then re-printed in other papers across the

South. The text was sent to me by Justin Sanders, who also helped

with figuring out who the three men might have been. |

|

|

Charleston Daily Courier [From the Southern Guardian.] Letter from Hon. W.W. Boyce.

SABINE

FARM, August 3, 1860.

Gentlemen:—My high respect for you induces me to hasten a reply to your note. If To comprehend the full significance of The vital principle of this party is negro equality, the only logical finale of which is emancipation. To see this, it is only necessary to look at their platform, which though intended for obvious reasons of policy to appear conservative, yet raises the veil in part. This platform says "we hold that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty," &c.; and this on motion of Mr. Giddings. This is intended to include negros. It follows, therefore, according to Republican faith, that no one can be rightfully held in slavery. Slavery, then, is a great wrong. The Republican party are bound, therefore,

so far as their constitutional

power goes, to remove that wrong. At

present

their practical point of attack is the Territories; when this question

shall not

longer exist, then the By the character of this party, I mean its

sectionalism. It is a party confined

entirely to the Northern

States—both its candidates

are Northern men. The idea of the majority

section banding together for the purpose of seizing

upon the Government, is at war with the spirit of the Constitution. The great idea of the Constitution is the

equality

of the States. The seizure of the

Government

by one section is a practical revolution in the Government. The Northern States then become the master

States,

and the Southern States sink into an inferior condition. This is not

the The new order of things which the Republican party propose to introduce, would be inaugurated by the administration of Lincoln, a Northern Abolitionist, who would humble the South. Between these two administrations what a profound gulf. The first representing the perfect equality of the States; the second would represent the domination of the North and the subjugation of the South. A half-dozen unsuccessful campaigns could not put the South in a more abject condition. By the sentiments of this party I mean its antagonism to the South. It requires no elaborate proof to show that the feeling of this party is that of hostility to the South. The tone of the Republican press, the temper of public speeches, such as are delivered by Sumner and Lovejoy and other leading men of the party, the sympathy for John Brown, the very agitation of the slavery question, and numerous other facts which might be cited, show that the great passion on which the Republican party rests is hatred to the South. Such being the Republican party, for the South to consent to its domination is to consent to death. Not that I apprehend any startling measures of aggression by this party immediately. No, its policy is too obviously a wise moderation, and its leaders are men of too much sagacity to be driven ahead of their programme. But the mere fact of such a party taking possession of the Federal Government, with the acquiescence of the South, will be the most fatal blow the South has ever received. The whole power and patronage of the Government will be placed upon the side of negro equality; the Northern majority adverse to us will be stimulated to new life; they will feel the exultation of being the master States. The Southern States, on the other hand, will be wounded in their prestige. Their equality gone, hopeless of the future, they will be prepared for defeat because they will have despaired of victory. Great as are the moral effects, important practical results would also speedily follow. The patronage of the Administration would be used to build up a Republican party in the border slave States; and the Federal Judiciary would be remodeled, so that the dogmas of fanaticism would become the decrees of the Supreme Court. Nor could we obtain peace by an abject submission, if so inclined; the agitation would go on with increased volume when it was found not to be hazardous, and we would ultimately be forced to yield all, or to resist under circumstances infinitely more discouraging than exist at present. To acquiesce in the vast powers of the Federal Government going into the hands of our would-be masters, with the intention of resisting at some future time, would be emulate the infatuation of the Numidian King, who delivered his treasures, his arms, his elephants and his deserters to the Romans, and then renewed the war, having needlessly deprived himself of the means of defence. If the South acquiesces in a Republican

Administration, I think

the question of negro equality is settled against us, and emancipation

only a question

of time. I have regarded this question in

the same light for years, and I have considered the success of the

Republican party

in the Presidential election as involving the necessity of revolution.

So regarding

it, I have thought the great paramount object of our policy was to let

this Republican

success occur, if it must occur, under the most auspicious

circumstances for a disruption,

and those auspicious circumstances I thought would consist principally

in the largest

attainable sympathy North, and the greatest unity South.

These conditions I thought were most likely to

be reached by a wise and prudent moderation on the part of the South. And I accordingly advised and acted in that

direction,

and I am satisfied I never gave wiser counsels. I

said to my constituents last Summer, that we must act with most

consummate

prudence then, in order to

profit by most desperate boldness if it became necessary—prudence to give pretext for the election of a Republican, boldness to

relieve ourselves

from such election if it must take place. My policy

was a consistent policy—prudence,

when prudence might be advantageous;

boldness, when nothing else was left. The

time is now approaching when in my opinion the only alternative will be

boldness. If the Republican party triumph

in the Presidential

election, our State has no choice but to immediately withdraw from the Suppose we have done this. Then only two courses remain to our enemies: first, they must let us alone; secondly, they must attempt to coerce us. Either alternative will accomplish our purpose. Suppose they let us alone—very good. We will have free trade with Suppose they undertake to coerce us. Then the Southern States are compelled to make common cause with us, and we will wake up some morning and find the flag of a Southern Confederacy floating over us. That would be a great deal better than paying tribute to the John Brown sympathisers. The South still has splendid cards in her

hands if she will only

play them. The constitution of Northern

society

is artificial in the extreme. Immense

wealth

has been accumulated there. A few are

richer

than the Kings of the East; the multitude labor for their daily bread;

much of this

wealth is breath—the breath

of credit. A civil convulsion will bring

their paper system of credit tumbling about

their ears. The first gun fired in civil

war will cost them $500,000,000, and strikes will not be confined to

shoemakers,

but will become epidemic. If Let us show that we can grasp the sword as well as they can; that we are not degenerate descendants of those glorious heros from whom we draw our lineage. If the worst come to the worst, we can but fall, sword in hand, fighting for all that makes life desirable—justice, equality, and our country. But I have no fear as to the result, if it comes to a question of arms. We can give blows as well as receive them, and we are as apt to have our Winter quarters in the city of New York, as they theirs in New Orleans. But we do not desire war.

We wish peace and fraternity in the Union, if possible;

but one thing there

is which we are determined to have, in the WILLIAM W. BOYCE. Messrs. D.L. Provence, W.S. Lyles. |

Back to Causes of the Civil War (Main page) Back to State and Local Resolutions and Correspondence Back to Editorial Commentary Source: Scanned image of archived newspaper Date added to website: June 27, 2023 |