|

ANNAPOLIS,

MD., December 28, 1860.

Hon.

THOMAS H. HICKS,

Annapolis, Md.:

SIR:

The Governor of the sovereign State of Alabama

has appointed me a commissioner to the sovereign State of

Maryland "to consult and advise" with the Governor and

Legislature thereof "as to what is best to be done to

protect the rights, interests, and honor of the slave-holding

States," menaced and endangered by recent political events.

Having watched with painful anxiety the growth, power, and

encroachments of anti-slaveryism, and anticipating for the party

held together by this sentiment of hostility to the rights and

institutions of the Southern people a probable success, too

fatally realized, in the recent Presidential election, the

General Assembly of Alabama, on the 24th of February, 1860,

adopted joint resolutions providing, on the happening of such a

contingency, for a convention of the State "to consider,

determine, and do whatever the rights, interests, and honor of

Alabama require to be done for their protection." In

accordance with this authority the Governor has called a

convention to meet on the 7th day of January, 1861, and on the

24th instant delegates were elected to that body. Not content

with this simple but significant act of convoking the sovereignty

of the people, the State affirmed her reserved and undelegated

right of secession from the confederacy, and intimated that

continued and unceasingly violent assaults upon her rights and

equality might "constrain her to a reluctant but early

exercise of that invaluable right." Recognizing the common

interests and destiny of all the States holding property in the

labor of Africans, and "anxiously desiring their

co-operation in a struggle which perils all they hold most

dear," Alabama pledged herself to a "cordial

participation in any and every effort which, in her judgment,

will protect the common safety, advance the common interest, and

serve the common cause."

To

secure concert and effective co-operation between

Maryland and Alabama is in a great degree the object of my

mission. Under our federative system each State, being

necessarily the sole judge of the extent of powers delegated to

the general agent and controlling the allegiance of her citizens,

must decide for herself in case of wrong upon the mode and

measure of redress. Within the Union the States have absolutely

prohibited themselves from entering into treaties, alliances, and

confederations, and have made the assent of Congress a condition

precedent to their entering into agreements or compacts with

other States. This constitutional inhibition has been construed

to include "every agreement, written or verbal, formal or

informal, positive or implied, by the mutual understanding of the

parties." Without indorsing this sweeping judicial dictum,

it will be conceded that if the grievance or apprehension of

danger be so great as to render necessary or advisable a

withdrawal from the confederacy there can be between the States

similarly imperiled, prior to separation, only an informal

understanding for prospective concert and federation. To enter

into a binding "agreement or compact" would violate the

Constitution, and the South should be careful not to part with

her distinguishing glory of having never, under the most

aggravating provocations, departed from the strictest

requirements of the Federal covenant nor suggested any

proposition infringing upon the essential equality of the

co-States. It is, nevertheless, the highest dictate of wisdom and

patriotism to secure, so far as can be constitutionally done,

"a mutual league, united thoughts and counsels,"

between those whose hopes and hazards are alike joined in the

enterprise of accomplishing deliverance from Abolition

domination. To Your Excellency or so intelligent a body as the

Legislature of Maryland it would be superfluous to enter into an

elaborate statement of the policy and purposes of the party

which, by the recent election, will soon have the control of the

General Government. The bare fact that the party is sectional and

hostile to the South is a full justification for the

precautionary steps taken by Alabama to provide for the escape of

her citizens from the peril and dishonor of submission to its

rule. Superadded to the sectional hostility the fanaticism of a

sentiment which has become a controlling political force, giving

ascendancy in every Northern State, and the avowed purpose, as

disclosed in party creeds, declarations of editors, and

utterances of representative men, of securing the diminution of

slavery in the States and placing it in the course of ultimate

extinction, and the South would merit the punishment of the

simple if she passed on and provided no security against the

imminent danger.

When

Mr. Lincoln is inaugurated it will not be simply

a change of administration--the installation of a new

President--but a reversal of the former practice and policy of

the Government, so thorough as to amount to a revolution. Cover

over its offensiveness with the most artful disguises, and the

fact stands out in its terrible reality that the Government,

within the amplitude of its jurisdiction, real or assumed,

becomes foreign to the South, and is not to recognize the right

of the Southern citizen to property in the labor of African

slaves. Heretofore Congress, the Executive, and the judiciary

have considered themselves, in their proper spheres, as under a

constitutional obligation to recognize and protect as property

whatever the States ascertained and determined to be such. Now,

the opinion of nearly every Republican is, that the slave of a

citizen of Maryland, in possession of and in company with his

master, on a vessel sailing from Baltimore to Mobile, is as free

as his master, entitled to the same rights, privileges, and

immunities, as soon as a vessel has reached a marine league

beyond the shores of a State and is outside the jurisdiction of

State laws. The same is held if a slave be carried on the

territory or other property belonging to the United States, and

it is denied by all Republicans that Congress or a Territorial

Legislature or any individuals can give legal existence to

slavery in any Territory of the United States. Thus, under the

new Government, property which existed in every one of the States

save one when the Government was formed, and is recognized and

protected in the Constitution, is to be proscribed and outlawed.

It requires no argument to show that States whose property is

thus condemned are reduced to inferiority and inequality.

Such

being the principles and purposes of the new

Government and its supporters, every Southern State is deeply

interested in the protection of the honor and equality of her

citizens. Recent events occurring at the Federal capital and in

the North must demonstrate to the most incredulous and hopeful

that there is no intention on the part of the Republicans to make

concessions to our just and reasonable demands or furnish any

securities against their wrongdoing. If their purposes were right

and harmless, how easy to give satisfactory assurances and

guaranties. If no intention to harm exists, it can be neither

unmanly nor unwise to put it out of their power to commit harm.

The minority section must have some other protection than the

discretion or sense of justice of the majority, for the

Constitution as interpreted, with a denial of the right of

secession or State interposition, affords no security or means of

redress against a hostile and fanatical majority. The action of

the two committees in the Senate and House of Congress shows an

unalterable purpose on the part of the Republicans to reap the

fruits of their recent victory, and to abate not a jot or tittle

of their Abolition principles. They refuse to recognize our

rights of property in slaves, to make a division of the

territory, to deprive themselves of their assumed constitutional

power to abolish slavery in the Territories or District of

Columbia, to increase the efficiency of the fugitive slave law,

or make provision for the compensation of the owners of runaway

or stolen slaves, or place in the hands of the South any

protection against the rapacity of an unscrupulous majority.

If

our present undoubted constitutional rights were

reaffirmed in, if possible, more explicit language, it is

questionable whether they would meet with more successful

execution. Anti-slavery fanaticism would probably soon render

them nugatory. The sentiment of the sinfulness of slavery seems

to be embedded in the Northern conscience. An infidel theory has

corrupted the Northern heart. A French orator said the people of

England once changed their religion by act of Parliament. Whether

true or not, it is not probable that the settled convictions at

the North, intensely adverse to slavery, can be changed by

Congressional resolutions or constitutional amendments. Under

Republican rule the revolution will not be confined to slavery

and its adjuncts. The features of our political system which

constitute its chief excellence and distinguish it from absolute

governments are to be altered. The radical idea of this

confederacy is the equality of the sovereign States and their

voluntary assent to the constitutional compact. This, from recent

indications, is to be changed, so that to a great extent power is

to be centralized at Washington, Congress is to be the final

judge of its powers, States are to be deprived of a reciprocity

and equality of rights, and a common government, kept in being by

force, will discriminate offensively and injuriously against the

property of a particular geographical section.

With

Alabama, after patient endurance for years and

earnest expostulation with the Northern States, the reluctant

conviction has become fixed that there is no safety for her in a

hostile Union governed by an interested sectional majority. As a

sovereign State, vitally interested in the preservation and

security of African slavery, she will exercise the right of

withdrawing from the compact of union. Most earnestly does she

desire the co-operation of sister Southern States in a new

confederacy, based on the same principles as the present. Having

no ulterior or unavowed purposes to accomplish, seeking peace and

friendship with all people, determined that her slave population,

not to be increased by importations from Africa, shall not be

localized and become redundant by excess of growth beyond liberty

of expansion, she most cordially invites the concurrent action of

all States with common sympathies and common interests. Under an

abolition Government the slave-holding States will be placed

under a common ban of proscription, and an institution,

interwoven in the very frame-work of their social and political

being, must perish gradually or speedily with the Government in

active hostility to it. Instead of the culture and development of

the boundless capacities and productive resources of their social

system, it is to be assaulted, humbled, dwarfed, degraded, and

finally crushed out.

To

some of the States delaying action for new

securities the question of submission to a dominant abolition

majority is presented in a different form from what it was a few

weeks ago. One State has seceded; others will soon follow.

Without discussing the propriety of such action, the remaining

States must act on the facts as they exist, whether of their own

creation or approval or not. To unite with the seceding States is

to be their peers as confederates and have an identity of

interests, protection of property, and superior advantages in the

contest for the markets, a monopoly of which has been enjoyed by

the North. To refuse union with the seceding States is to accept

inferiority, to be deprived of an outlet for surplus slaves, and

to remain in a hostile Government in a hopeless minority and

remediless dependence. It gives me pleasure to be the medium of

communicating with you, and through you to the Legislature of

Maryland when it shall be convened. I trust that between Maryland

and Alabama, and other States having a homogeneous population,

kindred interests, and an inviting future of agricultural,

mining, mechanical, manufacturing, commercial, and political

success, a union, strong as the tie of affection and lasting as

the love of liberty, will soon be formed, which shall stand as a

model of a free, representative, constitutional, voluntary

republic.

I

have the honor to be, with much respect, your

obedient servant,

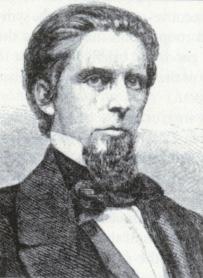

J. L. M. CURRY.

|