SIXTH JOINT DEBATE,

AT

October

13, 1858.

|

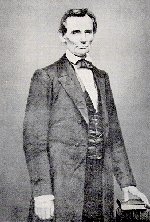

Lincoln

took some time in his opening speech to deny that he speaks

differently in northern and southern Illinois, and repeated

his assertion that the popular sovereignty doctrine

contradicted the Dred Scott decision. Douglas charged

that the slavery agitation then roiling the country was

entirely due to Abolition rhetoric, that questions of the

morality of slavery were not relevant, and that the

Republicans favor racial equality. Lincoln brought up a

new idea, that the Founders had intended the eventual

extinction of slavery. |

|

|

MR. LINCOLN'S SPEECH.

LADIES AND GENTLEMEN: I have had no immediate conference with Judge Douglas, but I will venture to say that he and I will perfectly agree that your entire silence, both when I speak and when he speaks, will be most agreeable to us.In

the month of May, I856, the elements in the State of The Convention that assembled in June last did me the honor, if it be one, and I esteem it such, to nominate me as their candidate for the United States Senate. I have supposed that, in entering upon this canvass, I stood generally upon these platforms. We are now met together on the 13th of October of the same year, only four months from the adoption of the last platform, and I am unaware that in this canvass, from the beginning until to-day, any one of our adversaries has taken hold of our platforms, or laid his finger upon any thing that he calls wrong in them. In

the very first one of these joint discussions between

Senator Douglas and myself, Senator Douglas, without

alluding at all to these platforms, or any one of them, of

which I have spoken, attempted to hold me responsible for a

set of resolutions passed long before the meeting of either

one of these Conventions of which I have spoken. And

as a ground for holding me responsible for these

resolutions, he assumed that they had been passed at a State

Convention of the Republican party, and that I took part in

that Convention. It was

discovered afterward that this was erroneous, that the

resolutions which he endeavored to hold me responsible for,

had not been passed by any State Convention any wherehad

not been passed at At Jonesboro, on our third meeting, I insisted to the Judge that I was in no way rightfully held responsible for the proceedings of this local meeting or Convention in which I had taken no part, and in which I was in no way embraced; but I insisted to him that if he thought I was responsible for every man or every set of men every where, who happen to be my friends, the rule ought to work both ways, and he ought to be responsible for the acts and resolutions of all men or sets of men who were or are now his supporters and friends, and gave him a pretty long string of resolutions, passed by men who are now his friends, and announcing doctrines for which he does not desire to be held responsible. This still does not satisfy Judge Douglas. He still adheres to his proposition, that I am responsible for what some of my friends in different parts of' the State have done; but that he is not responsible for what his have done. At least, so I understand him. But in addition to that, the Judge, at our meeting in Galesburgh, last week, undertakes to establish that I am guilty of a species of double-dealing with the publicthat I make speeches of a certain sort in the north, among the Abolitionists, which I would not make in the south, and that I make speeches of a certain sort in the south which I would not make in the north. I apprehend, in the course I have marked out for myself, that I shall not have to dwell at very great length upon this subject. As

this was done in the Judge's opening speech at Galesburgh, I

had an opportunity, as I had the middle speech then, of

saying something in answer to it. He

brought forward a quotation or two from a speech of mine,

delivered at Chicago, and then to contrast with it, he

brought forward an extract from a speech of mine at

Charleston, in which he insisted that I was greatly

inconsistent, and insisted that his conclusion followed that

I was playing a double part, and speaking in one region one

way, and in another region another way.

I have not time now to dwell on this as long as I

would like, and wish only now to requote that portion of my

speech at Yes, here you find men who hurra for Lincoln, and say he is right when he discards all distinction between races, or when he declares that he discards the doctrine that there is such a thing as a superior and inferior race; and Abolitionists are required and expected to vote for Mr. Lincoln because he goes for the equality of races, holding that in the Declaration of Independence the white man and negro were declared equal, and endowed by divine law with equality. And down south with the old line Whigs, with the Kentuckians, the Virginians, and the Tennesseeans, he tells you that there is a physical difference between the races, making the one superior, the other inferior, and he is in favor of maintaining the superiority of the white race over the negro. Those

are the Judge's comments. Now I

wish to show you, that a month, or, only lacking three days

of a month, before I made the speech at I have chiefly introduced this for the purpose of meeting the Judges charge that the quotation he took from my Charleston speech was what I would say down south among the Kentuckians, the Virginians, etc., but would not say in the regions in which was supposed to be more of the Abolition element. I now make this comment: That speech from which I have now read the quotation, and which is there given correctly, perhaps too much so for good taste, was made away up north in the Abolition District of this State par excellencein the Lovejoy Districtin the personal presence of Lovejoy, for he was on the stand with us when I made it. It had been made and put in print in that region only three days less than a month before the speech made at Charleston, the like of which Judge Douglas thinks I would not make where there was any Abolition element, I only refer to this matter to say that I am altogether unconscious of having attempted any double-dealing any wherethat upon one occasion I may say one thing and leave other things unsaid, and vice versa; but that I have said any thing on one occasion that is inconsistent with what I have said elsewhere, I denyat least I deny it so far as the intention is concerned. I find that I have devoted to this topic a larger portion of my time than I had intended. I wished to show, but I will pass it upon this occasion, that in the sentiment I have occasionally advanced upon the Declaration of Independence, I am entirely borne out by the sentiments advanced by our old Whig leader, Henry Clay, and I have the book here to show it from; but because I have already occupied more time than I intended to do on that topic, I pass over it. At Galesburgh, I tried to show that by the Dred Scott decision, pushed to its legitimate consequences, slavery would be established in all the States as well as in the Territories. I did this because, upon a former occasion, I had asked Judge Douglas whether, if the Supreme Court should make a decision declaring that the States had not the power to exclude slavery from their limits, he would adopt and follow that decision as a rule of political action; and because he had not directly answered that question, but had merely contented himself with sneering at it, I again introduced it, and tried to show that the conclusion that I stated followed inevitably and logically from the proposition already decided by the court. Judge Douglas had the privilege of replying to me at Galesburgh, and again he gave me no direct answer as to whether he would or would not sustain such a decision if made. I give him this third chance to say yes or no. He is not obliged to do eitherprobably he will not do eitherbut I give him the third chance. I tried to show then that this resultthis conclusion inevitably followed from the point already decided by the court. The Judge, in his reply, again sneers at the thought of the court making any such decision, and in the course of his remarks upon this subject, uses the language which I will now read. Speaking of me the Judge says: He

goes on and insists that the Dred Scott decision would carry

slavery into the I especially introduce this subject again for the purpose of saying that I have the Dred Scott decision here, and I will thank Judge Douglas to lay his finger upon the place in the entire opinions of the court where any one of them says the contrary. It is very hard to affirm a negative with entire confidence. I say, however, that I have examined that decision with a good deal of care, as a lawyer examines a decision, and so far as I have been able to do so, the court has no where in its opinions said that the States have the power to exclude slavery, nor have they used other language substantially that. I also say, so far as I can find, not one of the concurring Judges has said that the States can exclude slavery, nor said any thing that was substantially that. The nearest approach that any one of them has made to it, so far as I can find, was by Judge Nelson, and the approach he made to it was exactly, in substance, the Nebraska Billthat the States had the exclusive power over the question of slavery, so far as they are not limited by the Constitution of the United States. I asked the question therefore, if the non-concurring Judges, McLean or Curtis, had asked to get an express declaration that the States could absolutely exclude slavery from their limits, what reason have we to believe that it would not have been voted down by the majority of the Judges, just as Chases amendment was voted down by Judge Douglas and his compeers when it was offered to the Nebraska Bill. Also

at Galesburgh, I said something in regard to those A voiceIt's the same thing with you. Mr. The Judge, in his concluding speech at Galesburgh, says that I was pushing this matter to a personal difficulty, to avoid the responsibility for the enormity of my principles. I say to the Judge and this audience now, that I will again state our principles as well as I hastily can in all their enormity, and if the Judge hereafter chooses to confine himself to a war upon these principles, he will probably not find me departing from the same course. We

have in this nation this element of domestic slavery.

It is a matter of absolute certainty that it is a

disturbing element. It is the

opinion of all the great men who have expressed an opinion

upon it, that it is a dangerous element.

We keep up a controversy in regard to it.

That controversy necessarily springs from

difference of opinion, and if we can learn exactlycan

reduce to the lowest elementswhat that difference of

opinion is, we perhaps shall be better prepared for

discussing the different systems of policy that we would

propose in regard to that disturbing element.

I suggest that the difference of opinion, reduced

to its lowest terms, is no other than the difference between

the men who think slavery a wrong and those who do not think

it wrong. The Republican party

think it wrongwe think it is a moral, a social and a

political wrong. We think it as

a wrong not confining itself merely to the persons or the

States where it exists, but that it is a wrong in its

tendency, to say the least, that extends itself to the

existence of the whole nation. Because

we

think it wrong, we propose a course of policy that shall

deal with it as a wrong. We

deal with it as with any other wrong, in so far as we can

prevent its growing any larger, and so deal with it that in

the run of time there may he some promise of an end to it. We have a due regard to the actual

presence of it amongst us and the difficulties of getting

rid of it in any satisfactory way, and all the

Constitutional obligations thrown about it.

I suppose that in reference both to its actual

existence in the nation, and to our Constitutional

obligations, we have no right at all to disturb it in the

States where it exists, and we profess that we have no more

inclination to disturb it than we have the right to do it. We go further than that; we don't

propose to disturb it where, in one instance, we think the

Constitution would permit us. We

think the Constitution would permit us to disturb it in the

We oppose the Dred Scott decision in a certain way, upon which I ought perhaps to address you a few words. We do not propose that when Dred Scott has been decided to be a slave by the court, we, as a mob, will decide him to be free. We do not propose that, when any other one, or one thousand, shall be decided by that court to be slaves, we will in any violent way disturb the rights of property thus settled but we nevertheless do oppose that decision as a political rule, which shall be binding on the voter to vote for nobody who thinks it wrong, which shall be binding on the members, of Congress or the President to favor no measure that does not actually concur with the principles of that decision. We do not propose to be bound by it as a political rule in that way, because we think it lays the foundation not merely of enlarging and spreading out what we consider an evil, but it lays the foundation for spreading that evil into the States themselves. We propose so resisting it as to have it reversed if we can, and a new judicial rule established upon this subject. I will add this, that if there be any man who does not believe that slavery is wrong in the three aspects which I have mentioned, or in any one of them, that man is misplaced, and ought to leave us. While, on the other hand, if there be any man in the Republican party who is impatient over the necessity springing from its actual presence, and is impatient of the Constitutional guaranties thrown around it, and would act in disregard of these, he too is misplaced, standing with us. He will find his place somewhere else; for we have a due regard, so far as we are capable of understanding them, for all these things. This, gentlemen, as well as I can give it, is a plain statement of our principles in all their enormity. I will say now that there is a

sentiment in the country contrary to mea sentiment which

holds that slavery is not wrong, and therefore it goes for

the policy that does not propose dealing with it as a

wrong. That policy is the Democratic policy, and

that sentiment is the Democratic sentiment. If there

be a doubt in the mind of any one of this vast audience

that this is really the central idea of the Democratic

party, in relation to this subject, I ask him to bear with

me while I state a few things tending, as I think, to

prove that proposition. In the first place, the

leading manI think I may do my friend Judge Douglas the

honor of calling him suchadvocating the present

Democratic policy, never himself says it is wrong.

He has the high distinction, so far as I know, of never

having said slavery is either right or wrong. Almost

every body else says one or the other, but the Judge never

does. If there be a man in the Democratic party who

thinks it is wrong, and yet clings to that party, I

suggest to him in the first place that his leader don't

talk as he does, for he never says that it is wrong.

In the second place, I suggest to him that if he will

examine the policy proposed to be carried forward, he will

find that he carefully excludes the idea that there is any

thing wrong in it. If you will examine the arguments

that are made on it, you will find that every one

carefully excludes the idea that there is any thing wrong

in slavery. Perhaps that Democrat who says he is as

much opposed to slavery as I am, will tell me that I am

wrong about this. I wish him to examine his own

course in regard to this matter a moment, and then see if

his opinion will not be changed a little. You say it

is wrong; but don't you constantly object to any body else

saying so? Do you not constantly argue that this is

not the right place to oppose it? You say it must

not be opposed in the free States, because slavery is not

here; it must not be opposed in the slave States, because

it is there; it must not be opposed in politics, because

that will make a fuss; it must not be opposed in the

pulpit, because it is not religion. Then where is

the place to oppose it? There is no suitable place

to oppose it. There is no plan in the country to

oppose this evil overspreading the continent, which you

say yourself is coming. Frank Blair and Gratz Brown

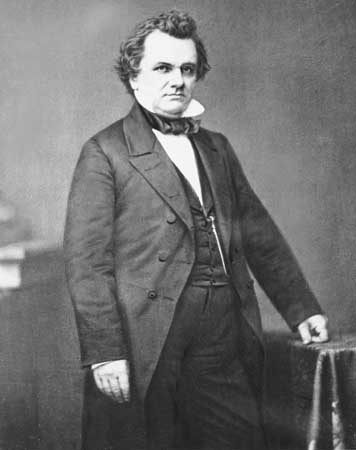

tried to get up a system of gradual emancipation in MR. LADIES AND GENTLEMEN: Permit me to say that unless silence is observed it will be impossible for me to be heard by this immense crowd, and my friends can confer no higher favor upon me than by omitting all expressions of applause or approbation. I desire to be heard rather than to be applauded. I wish to address myself to your reason, your judgment, your sense of justice, and not to your passions.I

regret that Mr. Lincoln should have deemed it proper for him

to again indulge in gross personalities and base

insinuations in regard to the I

will now show you that I stated with entire fairness, as

soon as it was made known to me, that there was a mistake

about the spot where the resolutions had been adopted,

although their truthfulness, as a declaration of the

principles of the Republican party, had not and could not be

questioned. I did not wait for

Now,

let me call your attention for a moment to the answers which

Mr. Lincoln made at Freeport to the questions which I

propounded him at Ottawa, based upon the platform adopted by

a majority of the Abolition counties of the State, which now

as then supported him. In

answer to my question whether he indorsed the Black

Republican principle of no more slave States, he answered

that he was not pledged against the admission of any more

slave States, but that he would be very sorry if he should

ever be placed in a position where he would have to vote on

the question; that he would rejoice to know that no more

slave States would be admitted into the Union; but, he

added, if slavery shall be kept out of the Territories

during the territorial existence of any one given Territory,

and then the people shall having a fair chance and a clear

field when they come to adopt the Constitution, do such an

extraordinary thing as to adopt a slave Constitution,

uninfluenced by the actual presence of the institution among

them, I see no alternative, if we own the country, but to

admit them into the Union. The

point I wish him to answer is this: Suppose Congress should

not prohibit slavery in the Territory, and it applied for

admission with a Constitution recognizing slavery, then how

would he vote? His answer at Mr.

Lincoln complains that, in my speech the other day at

Galesburgh, I read an extract from a speech delivered by him

at Chicago, and then another from his speech at Charleston,

and compared them, thus showing the people that he had one

set of principles in one part of the State and another in

the other part. And how does he

answer that charge? Why, he

quotes from his I should like to know, if taking this old Declaration of Independence, which declares that all men are equal upon principle, and making exceptions to it, where will it stop? If one man says it does not mean a negro, why may not another man say it does not mean another man? If that declaration is not the truth, let us get this statute book in which we find it and tear it out. There

you find that Mr. Lincoln told the Abolitionists of Chicago

that if the Declaration of Independence did not declare that

the negro was created by the Almighty the equal of the white

man, that you ought to take that instrument and tear out the

clause which says that all men were created equal.

But let me call your attention to another part of

the same speech. You know that

in his My friends, I have detained you about as long as I desire to do, and I have only to say let us discard all this quibbling about this man and the other manthis race and that race, and the other race being inferior, and therefore they must be placed in an inferior position, discarding our standard that we have left us. Let us discard all these things, and unite as one people throughout this land until we shall once more stand up declaring that all men are created equal. Thus

you see, that when addressing the Chicago Abolitionists he

declared that all distinctions of race must be discarded and

blotted out, because the negro stood on an equal footing

with the white man; that if one man said the Declaration of

Independence did not mean a negro when it declared all men

created equal, that another man would say that it did not

mean another man; and hence we ought to discard all

difference between the negro race and all other races, and

declare them all created equal. Did

old Giddings, when he came down among you four years ago,

preach more radical Abolitionism than this?

Did Lovejoy, or Lloyd

Garrison, or Wendell Phillips, or Fred Douglass, ever take

higher Abolition grounds than that? Lincoln

told you that I had charged him with getting up these

personal attacks to conceal the enormity of his principles,

and then commenced talking about something else, omitting to

quote this part of his Chicago speech which contained the

enormity of his principles to which I alluded.

He knew that I alluded to his negro-equality

doctrines when I spoke of the enormity of his principles,

yet he did not find it convenient to answer on that point. Having shown you what he said in

his I will say then, that I am not nor ever have been in favor of bringing about in any way, the social and political equality of the white and black races; that I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters of the the free negroes, or jurors, or qualifying them to hold office, or having them to marry with white people. I will say in addition, that there is a physical difference between the white and black races, which, I suppose, will forever forbid the two races living together upon terms of social and political equality, and inasmuch as they cannot so live, that while they do remain together, there must be the position of superior and inferior, that I as much as any other man am in favor of the superior position being assigned to the white man. A voiceThat's the doctrine. Mr.

DouglasYes, sir, that is good doctrine, but Mr. This

Republican organization appeals to the North against the

South; it appeals to northern passion, northern prejudice,

and northern ambition, against southern people, southern

States, and southern institutions, and its only hope of

success is by that appeal. Mr.

Lincoln goes on to justify himself in making a war upon

slavery, upon the ground that Frank Blair and Gratz Brown

did not succeed in their warfare upon the institutions in Under

the operation of that policy the agitation has not only not

ceased, but has constantly augmented. In

my opinion it will not cease until a crisis shall have been

reached and passed. A house

divided against itself cannot stand. I

believe this Government cannot endure permanently half slave

and half free. I do not expect

the Mr.

Lincoln there told his Abolition friends that this

Government could not endure permanently, divided into free

and slave States as our fathers made it, and that it must

become all free or all slave, otherwise, that the Government

could not exist. How then does

He

tells you that I will not argue the question whether slavery

is right or wrong. I tell you

why I will not do it. I hold

that under the Constitution of the But

Mr. Lincoln says that I will not answer his question as to

what I would do in the event of the court making so

ridiculous a decision as he imagines they would by deciding

that the A voiceThe same thing was said about the Dred Scott decision before it passed. Mr. DouglasPerhaps you think that the court did the same thing in reference to the Dred Scott decision: I have heard a man talk that way before. The principles contained in the Dred Scott decision had been affirmed previously in various other decisions. What court or judge ever held that a negro was a citizen? The State courts had decided that question over and over again, and the Dred Scott decision on that point only affirmed what every court in the land knew to be the law. But,

I will not be drawn off into an argument upon the merits of

the Dred Scott decision. It is

enough for me to know that the Constitution of the I

have never yet been able to make Mr. Lincoln understand, nor

can I make any man who is determined to support him, right

or wrong, understand how it is that under the Dred Scott

decision the people of a Territory, as well as a State, can

have slavery or not, just as they please.

I believe that I can explain that proposition to

all Constitution-loving, law-abiding men in a way that they

cannot fail to understand it. Chief

Justice Taney, in his opinion in the Dred Scott case, said

that slaves being property, the owner of them has a right to

take them into a Territory the same as he would any other

property; in other words, that slave property, so far as the

right to enter a Territory is concerned, stands on the same

footing with other property. Suppose

we

grant that proposition. Then

any man has a right to go to Such

was the understanding when the Mr.

Lincoln and the We

propose to show that Judge Douglass action in 1850 and 1854

was taken with especial reference to the announcement of

doctrine and programme which was made at The

So much for the course taken by Judge Douglas on the Compromises of 1850. The record shows, beyond the possibility of cavil or dispute, that he expressly intended in those bills to give the Territorial Legislatures power to exclude slavery. How stands his record in the memorable session of 1854, with reference to the Kansas-Nebraska bill itself? We shall not overhaul the votes that were given on that notable measure. Our space will not afford it. We have his own words, however, delivered in his speech closing the great debate on that bill on the night of March 3, 1854, to show that he meant to do in 1854 precisely what he had meant to do in 1858. The Kansas-Nebraska bill being upon its passage, he said: It then quotes my remarks upon the passage of the bill as follows: The

principle which we propose to carry into effect by this bill

is this: That Congress shall neither legislate slavery into

any Territory or State nor out of the same; but the people

shall be left free to regulate their domestic concerns in

their own way, subject only to the Constitution of the Now,

let me ask, will those Senators who have arraigned me, or

any one of them, have the assurance to rise in his place and

declare that this great principle was never thought of or

advocated as applicable to territorial bills, in 1850; that,

from that session until the present, nobody ever thought of

incorporating this principle in all new territorial

organizations, etc., etc. I

will begin with the Compromises of 1850.

Any Senator who will take the trouble to examine

our journals will find that on the 25th of March

of that year I reported from the Committee on Territories

two bills, including the following measures: the admission

of The

Thus it is seen that, in framing the Nebraska-Kansas bill, Judge Douglas framed it in the terms and upon the model of those of Utah and New Mexico, and that in the debate he took pains expressly to revive the recollection of the voting which had taken place upon amendments affecting the powers of the Territorial Legislatures over the subject of slavery in the bills of 1850, in order to give the same meaning, force, and effect to the Nebraska-Kansas bill on this subject as had been given to those of Utah and New Mexico. The

The

recent legislation of Congress respecting domestic slavery,

derived as it has been from the original and pure fountain

of legitimate political power, the will of the majority,

promises ere long to allay the dangerous excitement.

This legislation is founded upon principles as

ancient as free government itself, and in accordance with

them has simply declared that the people of a Territory,

like those of a State, shall decide for themselves whether

slavery shall or shall not exist within their limits. Thus

you see that James Buchanan accepted the nomination at My

friends, I am told that my time is within two minutes of

expiring. I have omitted many

topics that I would liked to have discussed before you at

length. There were many points

touched by Mr. In conclusion, I desire to return to you my grateful acknowledgments for the kindness and the courtesy with which you have listened to me. It is something remarkable that in an audience as vast as this, composed of men of opposite politics and views, with their passions highly excited, there should be so much courtesy, kindness and respect exhibited not only toward one another, but toward the speakers, and I feel that it is due to you that I should thus express my gratitude for the kindness with which you have treated me.

MR. LINCOLN'S REJOINDER.

MY FRIENDS: Since Judge Douglas has said to you in his conclusion that he had not time in an hour and a half to answer all I had said in an hour, it follows of course that I will not be able to answer in half an hour all that he said in an hour and a half. I wish to return to Judge Douglas my profound thanks for his public annunciation here to-day, to be put on record, that his system of policy in regard to the institution of slavery contemplates that it shall last forever. We are getting a little nearer the true issue of this controversy, and I am profoundly grateful for this one sentence. Judge Douglas asks you, Why cannot the institution of slavery, or rather, why cannot the nation, part slave and part free, continue as our fathers made it forever? In the first place, I insist that our fathers did not make this nation half slave and half free, or part slave and part free. I insist that they found the institution of slavery existing here. They did not make it so, but they left it so because they knew of no way to get rid of it at that time. When Judge Douglas undertakes to say that, as a matter of choice, the fathers of the Government made this nation part slave and part free, he assumes what is historically a falsehood. More than that: when the fathers of the Government cut off the source of slavery by the abolition of the slave-trade, and adopted a system of restricting it from the new Territories where it had not existed, I maintain that they placed it where they understood, and all sensible men understood, it was in the course of ultimate extinction; and when Judge Douglas asks me why it cannot continue as our fathers made it, I ask him why he and his friends could not let it remain as our fathers made it? It is precisely all I ask of him in relation to the institution of slavery, that it shall be placed upon the basis that our fathers placed it upon. Mr. Brooks, of South Carolina, once said, and truly said, that when this Government was established, no one expected the institution of slavery to last until this day; and that the men who formed this Government were wiser and better than the men of these days; but the men of these days had experience which the fathers had not, and that experience had taught them the invention of the cotton-gin, and this had made the perpetuation of the institution of slavery a necessity in this country. Judge Douglas could not let it stand upon the basis which our fathers placed it, but removed it, and put it upon the cotton-gin basis. It is a question, therefore, for him and his friends to answerwhy they could not let it remain where the fathers of the Government originally placed it. I

hope nobody has understood me as trying to sustain the

doctrine that we have a right to quarrel with But

I have to hurry on, for I have but a half hour.

The Judge has informed me, or informed this

audience, that the Now,

in regard to this matter of the Dred Scott decision, I wish

to say a word or two. After

all, the Judge will not say whether, if a decision is made,

holding that the people of the States

cannot exclude slavery, he will support it or not.

He obstinately refuses to say what he will do in

that case. The Judges of the

Supreme Court as obstinately refused to say what they would

do on this subject. Before this

I reminded him that at Galesburgh he said the Judges had

expressly declared the contrary, and you remember that in my

opening speech I told him I had the book containing that

decision here, and I would thank him to lay his finger on

the place where any such thing was said.

He has occupied his hour and a half, and he has not

ventured to try to sustain his assertion.

He never will.

But he is desirous of knowing how we are going to

reverse the Dred Scott decision. Judge

Douglas ought to know how. Did

not he and his political friends find a way to reverse the

decision of that same court in favor of the

Constitutionality of the National Bank?

Didnt they find a way to do it so effectually that

they have reversed it as completely as any decision ever was

reversed, so far as its practical operation is concerned? And let me ask you, didnt Judge

Douglas find a way to reverse the decision of our Supreme

Court, when it decided that Carlins fatherold Governor

Carlinhad not the Constitutional power to remove a

Secretary of State? Did he not

appeal to the MOBS,

as he calls them? Did he not

make speeches in the lobby to show how villainous that

decision was, and how it ought to be overthrown? Did

he not succeed, too, in getting an act passed by the

Legislature to have it overthrown? And

didnt he himself sit down on that bench as one of the five

added judges, who were to overslaugh the four old

onesgetting his name of Judge in that way and no other? If there is a villainy in using

disrespect or making opposition to Supreme Court decisions,

I commend it to Judge Douglass earnest consideration. I know of no man in the State of Judge Douglas also makes the declaration that I say the Democrats are bound by the Dred Scott decision, while the Republicans are not. In the sense in which he argues, I never said it; but I will tell you what I have said and what I do not hesitate to repeat to-day. I have said that, as the Democrats believe that decision to be correct, and that the extension of slavery is affirmed in the National Constitution, they are bound to support it as such; and I will tell you here that General Jackson once said each man was bound to support the Constitution as he understood it. Now, Judge Douglas understands the Constitution according to the Dred Scott decision, and he is bound to support it as he understands it. I understand it another way, and therefore I am bound to support it in the way in which I understand it. And as Judge Douglas believes that decision to be correct, I will remake that argument if I have time to do so. Let me talk to some gentleman down there among you who looks me in the face. We will say you are a member of the Territorial Legislature, and like Judge Douglas, you believe that the right to take and hold slaves there is a Constitutional right. The first thing you do, is to swear you will support the Constitution and all rights guarantied therein; that you will, whenever your neighbor needs your legislation to support his Constitutional rights, not withhold that legislation. If you withhold that necessary legislation for the support of the Constitution and Constitutional rights, do you not commit perjury? I ask every sensible man, if that is not so? That is undoubtedly just so, say what you please. Now, that is precisely what Judge Douglas says, that this is a Constitutional right. Does the Judge mean to say that the Territorial Legislature in legislating may, by withholding necessary laws, or by passing unfriendly laws, nullify that Constitutional right? Does he mean to say that? Does he mean to ignore the proposition so long and well established in law, that what you cannot do directly, you cannot do indirectly? Does he mean that? The truth about the matter is this: Judge Douglas has sung paeans to his Popular Sovereignty doctrine until his Supreme Court, co-operating with him, has squatted his Squatter Sovereignty out. But he will keep up this species of humbuggery about Squatter Sovereignty. He has at last invented this sort of do-nothing Sovereigntythat the people may exclude slavery by a sort of Sovereignty that is exercised by doing nothing at all. Is not that running his Popular Sovereignty down awfully? Has it not got down as thin as the homoeopathic soup that was made by boiling the shadow of a pigeon that had starved to death? But at last, when it is brought to the test of close reasoning, there is not even that thin decoction of it left. It is a presumption impossible in the domain of thought. It is precisely no other than the putting of that most unphilosophical proposition, that two bodies can occupy the same space at the same time. The Dred Scott decision covers the whole ground, and while it occupies it, there is no room even for the shadow of a starved pigeon to occupy the same ground. Judge

Douglas, in reply to what I have said about having upon a

previous occasion made the speech at Now,

in relation to my not having said any thing about the

quotation from the What

is the foundation of this appeal to me in When

I sometimes, in relation to the organization of new

societies in new countries, where the soil is clean and

clear, insisted that we should keep that principle in view,

Judge Douglas will have it that I want a negro wife.

He never can be brought to understand that there is

any middle ground on this subject. I

have lived until my fiftieth year, and have never had a

negro woman either for a slave or a wife, and I think I can

live fifty centuries, for that matter, without having had

one for either. I maintain that

you may take Judge Douglass quotations from my The

Judge does not seem at all disposed to have peace, but I

find he is disposed to have a personal warfare with me. He says that my oath would not be

taken against the bare word of Charles H. Lanphier or Thomas

L. Harris. Well, that is

altogether a matter of opinion. It

is certainly not for me to vaunt my word against oaths of

these gentlemen, but I will tell Judge Douglas again the

facts upon which I dared to say they

proved a forgery. I pointed out

at Galesburgh that the publication of these resolutions in

the Illinois State Register could not have

been the result of accident, as the proceedings of that

meeting bore unmistakable evidence of being done by a man

who knew it was a forgery; that it was a

publication partly taken from the real proceedings of the

Convention, and partly from the proceedings of a Convention

at another place; which showed that he had the real

proceedings before him, and taking one part of the

resolutions, he threw out another part and substituted false

and fraudulent ones in their stead. I

pointed that out to him, and also that his friend Lanphier,

who was editor of the Register at that time

and now is, must have known how it was done.

Now whether he did it or got some

friend to do it for him, I could not tell, but he certainly

knew all about it. I pointed

out to Judge Douglas that in his This

is the third time that Judge Douglas has assumed that he

learned about these resolutions by Harriss attempting to

use them against Norton on the floor of Congress.

I tell Judge Douglas the public records of the

country show that he himself attempted it

upon I

am told that I still have five minutes left.

There is another matter I wish to call attention

to. He says, when he discovered

there was a mistake in that case, he came forward

magnanimously, without my calling his attention to it, and

explained it. I will tell you

how he became so magnanimous. When

the newspapers of our side had discovered and published it,

and put it beyond his power to deny it, then he came forward

and made a virtue of necessity by acknowledging it.

Now he argues that all the point there was in those

resolutions, although never passed at Then he wants to know why I wont withdraw the charge in regard to a conspiracy to make slavery national, as he has withdrawn the one he made. May it please his worship, I will withdraw it when it is proven false on me as that was proven false on him. I will add a little more than that. I will withdraw it whenever a reasonable man shall be brought to believe that the charge is not true. I have asked Judge Douglass attention to certain matters of fact tending to prove the charge of a conspiracy to nationalize slavery, and he says he convinces me that this is all untrue because Buchanan was not in the country at that time, and because the Dred Scott case had not then got into the Supreme Court; and he says that I say the Democratic owners of Dred Scott got up the case. I never did say that. I defy Judge Douglas to show that I ever said so, for I never uttered it. [One of Mr. Douglass reporters gesticulated affirmatively at Mr. Lincoln.] I dont care if your hireling does say I did, I tell you myself that I never said the Democratic owners of Dred Scott got up the case. I have never pretended to know whether Dred Scotts owners were Democrats or Abolitionists, or Freesoilers or Border Ruffians. I have said that there is evidence about the case tending to show that it was a made up case, for the purpose of getting that decision. I have said that that evidence was very strong in the fact that when Dred Scott was declared to be a slave, the owner of him made him free, showing that he had had the case tried and the question settled for such use as could be made of that decision; he cared nothing about the property thus declared to be his by that decision. But my time is out and I can say no more. |