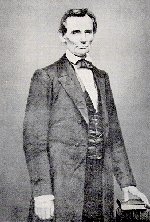

FIRST JOINT DEBATE, AT

August 21, 1858.

|

In

this,

the opening debate, both men tried to stake out basic themes

that might serve them over the entire series of debates.

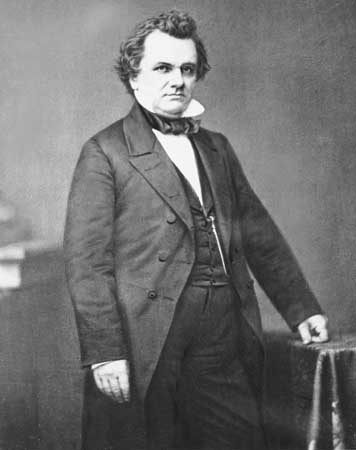

Douglas made it

abundantly clear that he intended to tie Lincoln to

abolition and the black race, referring to the Republican

Party uniformly as the "Black Republican party" or, simply,

the "Abolition party."

|

|

| He

also attacked Lincoln over his "House

Divided speech," delivered in July. For his part, Lincoln hammered Douglas for his indifference to the spread of slavery, something fomented by the 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act, which essentially repealed the 1820 Missouri Compromise. Lincoln also would repeatedly refer to the suggestion that the Dred Scott decision was somehow the result of a "corrupt bargain" between Senator Douglas, two Democratic Presidents (Pierce and Buchanan) and the Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court (Roger Taney). He also assured the audience that his cause was not the abolition of slavery, but stopping the spread of it, which he clearly believed would put it on the road to extinction. |

||

|

MR. DOUGLAS'S SPEECH.

LADIES AND GENTLEMEN:

I appear before you to-day for the purpose of

discussing the leading political topics which now agitate

the public mind. By an arrangement between Mr. Lincoln and

myself, we are present here to-day for the purpose of having

a joint discussion, as the representatives of the two great

political parties of the State and Union, upon the

principles in issue between those parties; and this vast

concourse of people shows the deep feeling which pervades

the public mind in regard to the questions dividing us. Prior to 1854 this country was divided into two

great political parties, known as the Whig and Democratic

parties. Both were national and patriotic, advocating

principles that were universal in their application. An

old line Whig could proclaim his principles in In 1851, the Whig party and the Democratic party

united in During the session of Congress of 1853-'54, I

introduced into the Senate of the United States a bill to

organize the Territories of Kansas and Nebraska on that

principle which had been adopted in the Compromise

measures of 1850, approved by the Whig party and the

Democratic party in Illinois in 1851, and indorsed by the

Whig party and the Democratic party in National Convention

in 1852. In order that there might be no misunderstanding

in relation to the principle involved in the Kansas and

Nebraska bill, I put forth the true intent and meaning of

the act in these words: "It is the true intent and meaning

of this act not to legislate slavery into any State or

Territory, or to exclude it therefrom, but to leave the

people, thereof perfectly free to form and regulate their

domestic institutions in their own way, subject only to

the Federal Constitution." Thus, you see, that up to 1854,

when the In 1854, Mr. Abraham Lincoln and Mr. Trumbull

entered into an arrangement, one with the other, and each

with his respective friends, to dissolve the old Whig

party on the one hand, and to dissolve the old Democratic

party on the other, and to connect the members of both

into an Abolition party, under the name and disguise of a

Republican party. The terms of that arrangement between

Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Trumbull have been published to the

world by Mr. Lincoln's special friend, James H. Matheny,

Esq., and they were, that Lincoln should have Shields's

place in the United States Senate, which was then about to

become vacant, and that Trumbull should have my seat when

my term expired. Lincoln went to work to Abolitionize the

old Whig party all over the State, pretending that he was

then as good a Whig as ever; and Trumbull went to work in

his part of the State preaching Abolitionism in its milder

and lighter form, and trying to Abolitionize the

Democratic party, and bring old Democrats handcuffed and

bound hand and foot into the Abolition camp.

In pursuance of the arrangement, the parties met

at 1. Resolved, That we believe this truth

to be self-evident, that when parties become subversive of

the ends for which they are established, or incapable of

restoring the Government to the true principles of the

Constitution, it is the right and duty of the people to

dissolve the political bands by which they may have been

connected therewith, and to organize new parties upon such

principles and with such views as the circumstances and

exigencies of the nation may demand. 2. Resolved, That the times imperatively

demand the reorganization of parties, and, repudiating all

previous party attachments, names and predilections, we

unite ourselves together in defense of the liberty and

Constitution of the country, and will hereafter cooperate

as the Republican party, pledged to the accomplishment of

the following purposes: To bring the administration of the

Government back to the control of first principles; to

restore Nebraska and Kansas to the position of free

Territories; that, as the Constitution of the United

States vests in the States, and not in Congress, the power

to legislate for the extradition of fugitives from labor,

to repeal and entirely abrogate the Fugitive Slave law; to

restrict slavery to those States in which it exists; to

prohibit the admission of any more slave States into the

Union; to abolish slavery in the District of Columbia; to

exclude slavery from all the Territories over which the

General Government has exclusive jurisdiction; and to

resist the acquirements of any more Territories unless the

practice of slavery therein forever shall have been

prohibited. 3. Resolved, That in furtherance of these

principles we will use such Constitutional and lawful

means as shall seem best adapted to their accomplishment,

and that we will support no man for office, under the

General or State Government, who is not positively and

fully committed to the support of these principles, and

whose personal character and conduct is not a guaranty

that he is reliable, and who shall not have abjured old

party allegiance and ties. Now, gentlemen, your Black Republicans have

cheered every one of those propositions, and yet I venture

to say that you cannot get Mr. Lincoln to come out and say

that he is now in favor of each one of them. That these

propositions, one and all, constitute the platform of the

Black Republican party of this day, I have no doubt; and

when you were not aware for what purpose I was reading

them, your Black Republicans cheered them as good Black

Republican doctrines. My object in reading these

resolutions, was to put the question to Abraham Lincoln

this day, whether he now stands and will stand by each

article in that creed, and carry it out.

I desire to know whether Mr. Lincoln to-day

stands as he did in 1854, in favor of the unconditional

repeal of the Fugitive Slave law. I desire him to answer

whether he stalls pledged to-day, as he did in 1854,

against the admission of any more slave States into the These

two men having formed this combination to abolitionize the

old Whig party and the old Democratic party, and put

themselves into the Senate of the Having

formed this new party for the benefit of deserters from

Whiggery, and deserters from Democracy, and having laid

down the Abolition platform which I have read, "In my opinion it will not cease until a crisis

shall have been reached and passed. 'A

house divided against itself cannot stand.' I

believe this government cannot endure

permanently half Slave and half Free. I

do not expect the ["Good," "good," and cheers.] I am delighted to hear you Black Republicans say

"good." I have no doubt that

doctrine expresses your sentiments, and I will prove to

you now, if you will listen to me, that it is

revolutionary and destructive of the existence of this

Government. Mr. Lincoln, in

the extract from which I have read, says that this

Government cannot endure permanently in the same condition

in which it was made by its framers—divided into free and

slave States. He says that it

has existed for about seventy years thus divided, and yet

he tells you that it cannot endure permanently on the same

principles and in the same relative condition in which our

fathers made it. Why can it

not exist divided into free and slave States? Washington,

Jefferson, Franklin, Madison, Hamilton, Jay, and the great

men of that day, made this Government divided into free

States and slave States, and left each State perfectly

free to do as it pleased on the subject of slavery. Why

can it not exist on the same principles on which our

fathers made it? They knew

when they framed the Constitution that in a country as

wide and broad as this, with such a variety of climate,

production and interest, the people necessarily required

different laws and institutions in different localities. They knew that the laws and

regulations which would suit the granite hills of New

Hampshire would be unsuited to the rice plantations of

South Carolina, and they, therefore, provided that each

State should retain its own Legislature and its own

sovereignty, with the full and complete power to do as it

pleased within its own limits, in all that was local and

not national. One of the reserved rights of the States,

was the right to regulate the relations between Master and

Servant, on the slavery question. At

the time the Constitution was framed, there were thirteen

States in the Union, twelve of which were We are told by Mr.

Lincoln, following the example and lead of all the little

Abolition orators, who go around and lecture in the

basements of schools and churches, reads from the

Declaration of Independence, that all men were created

equal, and then asks, how can you deprive a negro of that

equality which God and the Declaration of Independence

awards to him? He and they

maintain that negro equality is guarantied by the laws of

God, and that it is asserted in the Declaration of

Independence. If they think

so, of course they have a right to say so, and so vote. I do not question Mr. Lincoln's

conscientious belief that the negro was made his equal,

and hence is his brother; but for my own part, I do not

regard the negro as my equal, and positively deny that he

is my brother or any kin to me whatever. I am told that my time is out. Mr. Lincoln will now address you for an hour and a half, and I will then occupy an half hour in replying to him.

MR. LINCOLN'S

REPLY. MY FELLOW

CITIZENS: When a man

hears himself somewhat misrepresented, it provokes him—at

least, I find it so with myself; but when

misrepresentation becomes very gross and palpable, it is

more apt to amuse him. The

first thing I see fit to notice, is the fact that Judge

Douglas alleges, after running through the history of the

old Democratic and the old Whig parties, that Judge

Trumbull and myself made an arrangement in 1854, by which

I was to have the place of Gen. Shields in the United

States Senate, and Judge Trumbull was to have the place of

Judge Douglas. Now, all I

have to say upon that subject is, that I think no man—not

even Judge Douglas—can prove it, because it

is not true. I have no

doubt he is “conscientious" in saying it. As

to those resolutions that he took such a length of time to

read, as being the platform of the Republican party in

1854, I say I never had anything to do with them, and I

think Now, about this story that Judge Douglas tells of

Now, gentlemen, I hate to waste my time on such

things, but in regard to that general Abolition tilt that

Judge Douglas makes, when he says that I was engaged at

that time in selling out and abolitionizing the old Whig

party—I hope you will permit me to read a part of a

printed speech that I made then at Peoria, which will show

altogether a different view of the position I took in that

contest of 1854. Voice—“Put on your specs.” Mr. Lincoln—Yes, sir, I am obliged to do so. I am no longer a young man. “This is the repeal of the Missouri Compromise.” The foregoing history may not be precisely accurate in every particular; but I am sure it is sufficiently so for all the uses I shall attempt to make of it, and in it we have before us, the chief materials enabling us to correctly judge whether the repeal of the Missouri Compromise is right or wrong. “I

think, and shall try to show, that it is wrong; wrong in its

direct effect, letting slavery into Kansas and Nebraska—and

wrong in its prospective principle, allowing it to spread to

every other part of the wide world, where men can be found

inclined to take it.” This declared indifference, but, as I must think, covert real zeal for the spread of slavery, I cannot but hate. I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself. I hate it because it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world—enables the enemies of free institutions, with plausibility, to taunt us as hypocrites—causes the real friends of freedom to doubt our sincerity, and especially because it forces so many really good men amongst ourselves into an open war with the very fundamental principles of civil liberty—criticising the Declaration of Independence, and insisting that there is no right principle of action but self-interest." Before proceeding, let me say I think I have no prejudice against the Southern people. They are just what we would be in their situation. If slavery did not now exist among them, they would not introduce it. If it did now exist amongst us, we should not instantly give it up. This I believe of the masses North and South. Doubtless there are individuals on both sides, who would not hold slaves under any circumstances; and others who would gladly introduce slavery anew, if it were out of existence. We know that some Southern men do free their slaves, go North, and become tip-top Abolitionists; while some Northern ones go South, and become most cruel slave-masters. "When

Southern people tell us they are no more responsible for the

origin of slavery than we, I acknowledge the fact. When

it is said that the institution exists, and that it is very

difficult to get rid of it, in any satisfactory way, I can

understand and appreciate the saying. I

surely will not blame them for not doing what I should not

know how to do myself. If all

earthly power were given me, I should not know what to do,

as to the existing institution. My

first impulse would be to free all the slaves, and send them

to "When

they remind us of their constitutional rights, I acknowledge

them, not grudgingly, but fully and fairly; and I would give

them any legislation for the reclaiming of their fugitives,

which should not, in its stringency, be more likely to carry

a free man into slavery, than our ordinary criminal laws are

to hang an innocent one." But

all this, to my judgment, furnishes no more excuse for

permitting slavery to go into our own free territory, than

it would for reviving the African slave-trade by law. The law which forbids the bringing

of slaves from Africa, and that which has so long forbid the

taking of them to I have reason to know that Judge Douglas knows that I said this. I think he has the answer here to one of the questions he put to me. I do not mean to allow him to catechise me unless he pays back for it in kind. I will not answer questions one after another, unless he reciprocates; but as he has made this inquiry, and I have answered it before, he has got it without my getting anything in return. He has got my answer on the Fugitive Slave law. Now,

gentlemen, I don't want to read at any greater length, but

this is the true complexion of all I have ever said in

regard to the institution of slavery and the black race. This is the whole of it, and

anything that argues me into his idea of perfect social and

political equality with the negro, is but a specious and

fantastic arrangement of words, by which a man can prove a

horse-chestnut to be a chestnut horse. I

will say here, while upon this subject, that I have no

purpose, directly or indirectly, to interfere with the

institution of slavery in the States where it exists. I believe I have no lawful right to

do so, and I have no inclination to do so. I

have no purpose to introduce political and social equality

between the white and the black races. There

is a physical difference between the two, which, in my

judgment, will probably forever forbid their living together

upon the footing of perfect equality, and inasmuch as it

becomes a necessity that there must be a difference, I, as

well as Judge Douglas, am in favor of the race to which I

belong having the superior position. I

have never said anything to the contrary, but I hold that,

notwithstanding all this, there is no reason in the world

why the negro is not entitled to all the natural rights

enumerated in the Declaration of Independence, the right to

life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. I hold that he

is as much entitled to these as the white man. I

agree with Judge Douglas he is not my equal in many

respects—certainly not in color, perhaps not in moral or

intellectual endowment. But in

the right to eat the bread, without the leave of anybody

else, which his own hand earns, he is my equal and the equal

of Judge Douglas, and the equal of every living man. Now

I pass on to consider one or two more of these little

follies. The Judge is woefully at fault about his early

friend Lincoln being a "grocery-keeper." I don't know as it

would be a great sin, if I had been; but he is mistaken. As

I have not used up so much of my time as I had supposed, I

will dwell a little longer upon one or two of these minor

topics upon which the Judge has spoken. He has read from my

speech in Now, my friends, I ask your attention to this matter for the purpose of saying something seriously. I know that the Judge may readily enough agree with me that the maxim which was put forth by the Saviour is true, but he may allege that I misapply it; and the Judge has a right to urge that, in my application, I do misapply it, and then I have a right to show that I do not misapply it. When he undertakes to say that because I think this nation, so far as the question of slavery is concerned, will all become one thing or all the other, I am in favor of bringing about a dead uniformity in the various States, in all their institutions, he argues erroneously. The great variety of the local institutions in the States, springing from differences in the soil, differences in the face of the country, and in the climate, are bonds of Union. They do not make “a house divided against itself” but they make a house united. If they produce in one section of the country what is called for by the wants of another section, and this other section can supply the wants of the first, they are not matters of discord but bonds of union, true bonds of union. But can this question of slavery be considered as among these, varieties in the institutions of the country? I leave it to you to say whether, in the history of our Government, this institution of slavery has not always failed to be a bond of union, and, on the contrary, been an apple of discord, and an element of division in the house. I ask you to consider whether, so long as the moral constitution of men's minds shall continue to be the same, after this generation and assemblage shall sink into the grave, and another race shall arise, with the same moral and intellectual development we have—whether, if that institution is standing in the same irritating position in which it now is, it will not continue an element of division? If so, then I have a right to say that, in regard to this question, the Union is a house divided against itself; and when the Judge reminds me that I have often said to him that the institution of slavery has existed for eighty years in some States, and yet it does not exist in some others, I agree to the fact, and I account for it by looking at the position in which our fathers originally placed it—restricting it from the new Territories where it had not gone, and legislating to cut off its source by the abrogation of the slave-trade, thus putting the seal of legislation against its spread. The public mind did rest in the belief that it was in the course of ultimate extinction. But lately, I think—and in this I charge nothing on the Judge's motives—lately, I think, that he, and those acting with him, have placed that institution on a new basis, which looks to the perpetuity and nationalization of slavery. And while it is placed upon this new basis, I say, and I have said, that I believe we shall not have peace upon the question until the opponents of slavery arrest the further spread of it, and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction; or, on the other hand, that its advocates will push it forward until it shall become alike lawful in all the States, old as well as new, North as well as South. Now, I believe if we could arrest the spread, and place it where Washington, and Jefferson, and Madison placed it, it would be in the course of ultimate extinction, and the public mind would, as for eighty years past, believe that it was in the course of ultimate extinction. The crisis would be past and the institution might be let alone for a hundred years, if it should live so long, in the States where it exists, yet it would be going out of existence in the way best for both the black and the white races. A

Voice—“Then do you repudiate Popular Sovereignty?” Mr. Lincoln—Well, then, let us talk about Popular Sovereignty! What is Popular Sovereignty? Is it the right of the people to have slavery or not have it, as they see fit, in the Territories? I will state—and I have an able man to watch me—my understanding is that Popular Sovereignty, as now applied to the question of slavery, does allow the people of a Territory to have slavery if they want to, but does not allow them not to have it if they do not want it. I do not mean that if this vast concourse of people were in a Territory of the United States, any one of them would be obliged to have a slave if he did not want one; but I do say that, as I understand the Dred Scott decision, if any one man wants slaves, all the rest have no way of keeping that one man from holding them. When

I made my speech at Now,

my friends, I wish you to attend for a little while to one

or two other things in that "We cannot absolutely know that these exact adaptations are the result of preconcert, but when we see a lot of framed timbers, different portions of which we know have been gotten out at different times and places, and by different workmen—Stephen, Franklin, Roger and James, for instance—and when we see these timbers joined together, and see they exactly make the frame of a house or a mill, all the tenons and mortices exactly fitting, and all the lengths and proportions of the different pieces exactly adapted to their respective places, and not a piece too many or too few—not omitting even the scaffolding—or if a single piece be lacking, we see the place in the frame exactly fitted and prepared yet to bring such piece in—in such a case we feel it impossible not to believe that Stephen and Franklin, and Roger and James, all understood one another from the beginning, and all worked upon a common plan or draft drawn before the first blow was struck." When

my friend, Judge Douglas, came to Chicago, on the 9th of

July, this speech having been delivered on the 16th of June,

he made an harangue there, in which he took hold of this

speech of mine, showing that he had carefully read it;

and while he paid no attention to this matter at all, but

complimented me as being a "kind, amiable and intelligent

gentleman," notwithstanding I had said this, he goes on and

eliminates, or draws out, from my speech this tendency of

mine to set the States at war with one another, to make all

the institutions uniform, and set the niggers and white

people to marrying together. Then,

as

the Judge had complimented me with these pleasant titles (I

must confess to my weakness), I was a little "taken," for it

came from a great man. I was

not very much accustomed to flattery, and it came the

sweeter to me. I was rather

like the Hoosier, with the gingerbread, when he said he

reckoned he loved it better than any other man, and got less

of it. As the Judge had so

nattered me, I could not make up my mind that he meant to

deal unfairly with me; so I went to work to show him that he

misunderstood the whole scope of my speech, and that I

really never intended to set the people at war with one

another. As an illustration,

the next time I met him, which was at In

a speech at Now, in regard to his reminding me of the moral rule that persons who tell what they do not know to be true, falsify as much as those who knowingly tell falsehoods. I remember the rule, and it must be borne in mind that in what I have read to you, I do not say that I know such a conspiracy to exist. To that I reply, I believe it. If the Judge says that I do not believe it, then he says what he does not know, and falls within his own rule, that he who asserts a thing which he does not know to be true, falsifies as much as he who knowingly tells a falsehood. I want to call your attention to a little discussion on that branch of the case, and the evidence which brought my mind to the conclusion which I expressed as my belief. If, in arraying that evidence, I had stated anything which was false or erroneous, it needed but that Judge Douglas should point it out, and I would have taken it back with all the kindness in the world. I do not deal in that way. If I have brought forward anything not a fact, if he will point it out, it will not even ruffle me to take it back. But if he will not point out anything erroneous in the evidence, is it not rather for him to show, by a comparison of the evidence, that I have reasoned falsely, than to call the “kind, amiable, intelligent gentleman” a liar? If I have reasoned to a false conclusion, it is the vocation of an able debater to show by argument that I have wandered to an erroneous conclusion. I want to ask your attention to a portion of the Nebraska bill, which Judge Douglas has emoted: “It being the true intent and meaning of this act, not to legislate slavery into any Territory or State, nor to exclude it therefrom, but to leave the people thereof perfectly free to form and regulate their domestic institutions in their own way, subject only to the Constitution of the United States." Thereupon Judge Douglas and others began to argue in favor of “Popular Sovereignty”—the right of the people to have slaves if they wanted them, and to exclude slavery if they did not want them. “But,” said, in substance, a Senator from Ohio (Mr. Chase, I believe), “we more than suspect that you do not mean to allow the people to exclude slavery if they wish to, and if you do mean it, accept an amendment which I propose expressly authorizing the people to exclude slavery." I believe I have the amendment here before me, which was offered, and under which the people of the Territory, through their proper representatives, might, if they saw fit, prohibit the existence of slavery therein. And now I state it as a fact, to betaken back if there is any mistake about it, that Judge Douglas and those acting with him voted that amendment down. I now think that those men who voted it down, had a real reason for doing so. They know what that reason was. It looks to us, since we have seen the Dred Scott decision pronounced, holding that, “under the Constitution,” the people cannot exclude slavery—I say it looks to outsiders, poor, simple, “amiable, intelligent gentlemen,” as though the niche was left as a place to put that Dred Scott decision in—a niche which would have been spoiled by adopting the amendment. And now, I say again, if this was not the reason, it will avail the Judge much' more to calmly and good-humoredly point out to these people what that other reason was for voting the amendment down, than, swelling himself up, to vociferate that he may be provoked to call somebody a liar. Again:

there is in that same quotation from the When

the Judge spoke at “I

did not answer the charge [of conspiracy] before, for the

reason that I did not suppose there was a man in I confess this is rather a curious view, that out of respect for me he should consider I was making what I deemed rather a grave charge in fun. I confess it strikes me rather strangely. But I let it pass. As the Judge did not for a moment believe that there was a man in America whose heart was so “corrupt” as to make such a charge, and as he places me among the “men in America” who have hearts base enough to make such a charge, I hope he will excuse me if I hunt out another charge very like this; and if it should turn out that in hunting I should find that other, and it should turn out to be Judge Douglas himself who made it, I hope he will reconsider this question of the deep corruption of heart he has thought fit to ascribe to me. In Judge Douglas's speech of March 22d, 1858, which I hold in my hand, he says: "In

this connection there is another topic to which I desire to

allude. I seldom refer to the

course of newspapers, or notice the articles which they

publish in regard to myself; but the course of the

Washington Union has been so extraordinary,

for the last two or three months, that I think it well

enough to make some allusion to it. It

has read me out of the Democratic party every other day, at

least for two or three months, and keeps reading me out,

and, as if it had not succeeded, still continues to read me

out, using such terms as “traitor,” “renegade,” “deserter,”

and other kind and polite epithets of that nature. Sir, I

have no vindication to make of my Democracy against the This

is a part of the speech. You

must excuse me from reading the entire article of the “Mr.

President, you here find several distinct propositions

advanced boldly by the “Remember that this article was

published in the Union on the 17th of

November, and on the 18th appeared the first article giving

the adhesion of the “

‘KANSAS AND HER CONSTITUTION.—The

vexed question is settled. The

problem is solved. The dead

point of danger is passed. All

serious trouble to “And

a column, nearly, of the same sort. Then,

when you come to look into the Lecompton Constitution, you

find the same doctrine incorporated in it which was put

forth editorially in the “ ‘Article 7, Section 1. The right of property is before and higher than any Constitutional sanction; and the right of the owner of a slave to such slave and its increase is the same and as inviolable as the right of the owner of any property whatever.’ “Then

in the schedule is a provision that the Constitution may be

amended after 1864 by a two-thirds vote. “ ‘But no alteration shall be made to affect the right of property in the ownership of slaves.’ “

‘It will be seen by these clauses in the Lecompton

Constitution, that they are identical in spirit with the authoritative article in the I pass over some portions of the speech, and I hope that any one who feels interested in this matter will read the entire section of the speech, and see whether I do the Judge injustice. He proceeds: “When I saw that article in the Union of the 17th of November, followed by the glorification of the Lecompton Constitution on the 18th of November, and this clause in the Constitution asserting the doctrine that a State has no right to prohibit slavery within its limits, I saw that there was a fatal blow being struck at the sovereignty of the States of this Union.” I

stop the quotation there, again requesting that it may all

be read. I have read all of the portion I desire to comment

upon. What is this charge that

the Judge thinks I must have a very corrupt heart to make? It was a purpose on the part of

certain high functionaries to make it impossible for the

people of one State to prohibit the people of any other

State from entering it with their “property,” so called, and

making it a slave State. In

other words, it was a charge implying a design to make the

institution of slavery national. And

now I ask your attention to what Judge Douglas has himself

done here. I know he made that

part of the speech as a reason why he had refused to vote

for a certain man for public printer, but when we get at it,

the charge itself is the very one I made against him, that

he thinks I am so corrupt for uttering. Now, whom does he

make that charge against? Does

he make it against that newspaper editor merely? No;

he says it is identical in spirit with the Lecompton

Constitution, and so the framers of that Constitution are

brought in with the editor of the newspaper in that “fatal

blow being struck.” He did not

call it a “conspiracy.” In his

language it is a “fatal blow being struck.”

And if the words carry the meaning better when

changed from a “conspiracy” into a “fatal blow being

struck,” I will change my expression and call it “fatal blow

being struck.” We see the

charge made not merely against the editor of the Is

there any question but he moans it was by the authority of

the President and his Cabinet—the Administration?

Is there any sort of question but he means to make

that charge? Then there are the

editors of the Union, the framers of the

Lecompton Constitution, the President of the Now,

my friends, I have but one branch of the subject, in the

little time I have left, to which to call your attention,

and as I shall come to a close at the end of that branch, it

is probable that I shall not occupy quite all the time

allotted to me. Although on

these questions I would like to talk twice as long as I

have, I could not enter upon another head and discuss it

properly without running over my time. I

ask the attention of the people here assembled and

elsewhere, to the course that Judge Douglas is pursuing

every day as bearing upon this question of making slavery

national. Not going back to the records, but taking the

speeches he makes, the speeches he made yesterday and day

before, and makes constantly all over the country—I ask your

attention to them. In the first

place, what is necessary to make the institution national? Not war. There is no danger that the

people of A Hibernian—“Give us something besides Drid [sic] Scott” Mr.

Lincoln—Yes; no doubt you want to hear something that don't

hurt. Now, having spoken of the

Dred Scott decision, one more word and I am done. Henry

Clay, my beau ideal of a statesman, the man for whom I

fought all my humble life—Henry Clay once said of a class of

men who would repress all tendencies to liberty and ultimate

emancipation, that they must, if they would do this, go back

to the era of our Independence, and muzzle the cannon which

thunders its annual joyous return; they must blow out the

moral lights around us; they must penetrate the human soul,

and eradicate there the love of liberty; and then, and not

till then, could they perpetuate slavery in this country! To my thinking, Judge Douglas is, by

his example and vast influence, doing that very thing in

this community, when he says that the negro has nothing in

the Declaration of Independence. Henry

Clay plainly understood the contrary. Judge

Douglas is going back to the era of our Revolution, and to

the extent of his ability, muzzling the cannon which

thunders its annual joyous return. When he invites any

people, willing to have slavery, to establish it, he is

blowing out the moral lights around us.

When he says he “cares not whether slavery is voted

down or voted up”—that it is a sacred right of

self-government he is, in my judgment, penetrating the human

soul and eradicating the light of reason and the love of

liberty in this American people. And

now I will only say that when, by all these means and

appliances, Judge Douglas shall succeed in bringing public

sentiment to an exact accordance with his own views—when

these vast assemblages shall echo back all these

sentiments—when they shall come to repeat his views and to

avow his principles, and to say all that he says on these

mighty questions then it needs only the formality of the

second Dred Scott decision, which he indorses in advance, to

make slavery alike lawful in all the States—old as well as

new, North as well as South. My

friends, that ends the chapter. The

Judge can take his half hour. MR. FELLOW CITIZENS:

I will now occupy the half hour allotted to me in replying

to Mr. Lincoln. The first point

to which I will call your attention is, as to what I said

about the organization of the Republican party in 1854, and

the platform that was formed on the fifth of October, of

that year, and I will then put the question to Mr. Lincoln,

whether or not, he approves of each article in that

platform, and ask for a specific answer. I

did not charge him with being a member of the committee

which reported that platform. I

charged that that platform was the platform of the

Republican party adopted by them. The

fact that it was the platform of the Republican party is not

denied, but Mr. Lincoln now says, that although his name was

on the committee which reported it, that he does not think

he was there, but thinks he was in Tazewell, holding court.

Now, I want to remind Mr. Lincoln that he was at The

point I am going to remind Mr. Lincoln of is this: that

after I had made my speech in 1854, during the fair, he gave

me notice that he was going to reply to me the next day. I was sick at the time, but I staid

over in In the first place, Mr. Lincoln was selected by the very men who made the Republican organization, on that day, to reply to me. He spoke for them and for that party, and he was the leader of the party; and on the very day he made his speech in reply to me, preaching up this same doctrine of negro equality, under the Declaration of Independence, this Republican party met in Convention. Another evidence that he was acting in concert with them is to be found in the fact that that Convention waited an hour after its time of meeting to hear Lincoln's speech, and Codding, one of their leading men, marched in the moment Lincoln got through, and gave notice that they did not want to hear me, and would proceed with the business of the Convention. Still another fact. I have here a newspaper printed at Springfield Mr. Lincoln's own town, in October, 1854, a few days afterward, publishing these resolutions, charging Mr. Lincoln with entertaining these sentiments, and trying to prove that they were also the sentiments of Mr. Yates, then candidate for Congress. This has been published on Mr. Lincoln over and over again, and never before has he denied it. But,

my friends, this denial of his that he did not act on the

committee, is a miserable quibble to avoid the main issue,

which is, that this Republican platform declares in favor of

the unconditional repeal of the Fugitive Slave law. Has

It is true he gives the Abolitionists to understand by a hint that he would not vote to admit such a State. And why? He goes on to say that the man who would talk about giving each State the right to have slavery, or not, as it pleased, was akin to the man who would muzzle the guns which thundered forth the annual joyous return of the day of our independence. He says that that kind of talk is casting a blight on the glory of this country. What is the meaning of that? That he is not in favor of each State to have the right of doing as it pleases on the slavery question? I will put the question to him again and again, and I intend to force it out of him. Then

again, this platform which was made at A voice —“How about the conspiracy?” Mr. Douglas—Never mind, I will come to that soon enough. But the platform which I have read to you, not only lays down these principles, but it adds: Resolved, That in furtherance of these principles we will use such constitutional and lawful means as shall seem best adapted to their accomplishment, and that we will support no man for office, under the General or State Government, who is not positively and fully committed to the support of these principles, and whose personal character and conduct is not a guaranty that he is reliable, and who shall not have abjured old party allegiance and ties. The Black Republican party stands pledged that they will never support Lincoln until he has pledged himself to that platform, but he cannot devise his answer; he has not made up his mind whether he will or not. He talked about everything else he could think of to occupy his hour and a half, and when he could not think of anything more to say, without an excuse for refusing to answer these questions, he sat down long before his time was out. In

relation to Mr. Lincoln's charge of conspiracy against me, I

have a word to say. In his

speech to-day he quotes a playful part of his speech at He

studied that out—prepared that one sentence with the

greatest care, committed it to memory, and put it in his

first I have not brought a charge of moral turpitude against him. When he, or anyother man, brings one against me, instead of disproving it, I will say that it is a he,and let him prove it if he can. I

have lived twenty-five years in Mr. Lincoln has not character enough for integrity and truth, merely on his own ipse dixit, to arraign President Buchanan, President Pierce, and nine Judges of the Supreme Court, not one of whom would be complimented by being put on an equality with him. There is an unpardonable presumption in a man putting himself up before thousands of people, and pretending that his ipse dixit, without proof, without fact and without truth, is enough to bring down and destroy the purest and best of living men. Fellow-citizens,

my time is fast expiring; I must pass on. Mr.

Lincoln wants to know why I voted against Mr. Chase's

amendment to the Mr.

Lincoln wants to know why the word “State,” as well as

“Territory,” was put into the Now you see that upon these very points I am as far from bringing Mr. Lincoln up to the line as I ever was before. He does not want to avow his principles. I do want to avow mine, as clear as sunlight in mid-day. Democracy is founded upon the eternal principle of right. The plainer these principles are avowed before the people, the stronger will be the support which they will receive. I only wish I had the power to make them so clear that they would shine in the heavens for every man, woman, and child to read. The first of those principles that I would proclaim would be in opposition to Mr. Lincoln's doctrine of uniformity between the different States, and I would declare instead the sovereign right of each State to decide the slavery question as well as all other domestic questions for themselves, without interference from any other State or power whatsoever. When

that principle is recognized, you will have peace and

harmony and fraternal feeling between all the States of this

Gentlemen, I am told that my time is out, and I am obliged to stop.

|