|

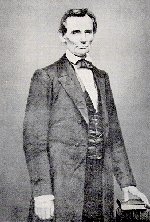

MR. DOUGLAS'S SPEECH.

LADIES AND GENTLEMEN:

Four years ago I appeared before the people of Knox county for

the purpose of defending my political action upon the Compromise

measures of 1850 and the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska bill. Those of you before me, who were

present then, will remember that I vindicated myself for

supporting those two measures by the fact that they rested upon

the great fundamental principle that the people of each State

and each Territory of this Union have the right, and ought to be

permitted to exercise the right, of regulating their own

domestic concerns in their own way, subject to no other

limitation or restriction than that which the Constitution of

the United States imposes upon them. I

then called upon the people of Illinois to decide whether

that principle of self-government was right or wrong.

If it was and is right, then the Compromise measures of

1850 were right, and, consequently, the Kansas and Nebraska

bill, based upon the same principle, must necessarily have been

right.

The

Kansas and Nebraska bill

declared, in so many words, that it was the true intent and

meaning of the act not to legislate slavery into any State

or Territory, nor to exclude it therefrom, but to leave the

people thereof perfectly free to form

and regulate their domestic institutions in their own way,

subject only to the Constitution of the United States. For the last four years I have

devoted all my energies, in private and public, to commend

that principle to the American people.

Whatever else may be said in condemnation or support

of my political course, I apprehend that no honest man will

doubt the fidelity with which, under all circumstances, I

have stood by it.

During

the last year a question arose in the Congress of the United States whether or

not that principle would be violated by the admission of Kansas into the Union

under the Lecompton Constitution. In

my opinion, the attempt to force Kansas in under that

Constitution, was a gross violation of the principle

enunciated in the Compromise measures of 1850, and Kansas

and Nebraska bill of 1854, and therefore I led off in the

fight against the Lecompton Constitution, and conducted it

until the effort to carry that Constitution through Congress

was abandoned. And I can appeal

to all men, friends and foes, Democrats and Republicans,

Northern men and Southern men, that during the whole of that

fight I carried the banner of Popular Sovereignty aloft, and

never allowed it to trail in the dust, or lowered my flag

until victory perched upon our arms. When

the Lecompton Constitution was defeated, the question arose

in the minds of those who had advocated it what they should

next resort to in order to carry put their views.

They devised a measure known as the English bill,

and granted a general amnesty and political pardon to all

men who had fought against the Lecompton Constitution,

provided they would support that bill.

I for one did not choose to accept the pardon, or to

avail myself of the amnesty granted on that condition. The fact that the supporters of

Lecompton were willing to forgive all differences of opinion

at that time in the event those who opposed it favored the

English bill, was an admission they did not think that

opposition to Lecompton impaired a man’s standing in the

Democratic party. Now the

question arises, what was that English bill which certain

men are now attempting to make a test of political orthodoxy

in this country. It provided,

in substance, that the Lecompton Constitution should be sent

back to the people of Kansas

for their adoption or rejection, at an election which was

held in August last, and in case they refused admission

under it, that Kansas

should be kept out of the Union

until she had 93,420 inhabitants. I

was in favor of sending the Constitution back in order to

enable the people to say whether or not it was their act and

deed, and embodied their will; but the other proposition,

that if they refused to come into the Union under it, they

should be kept out until they had double or treble the

population they then had, I never would sanction by my vote. The reason why I could not

sanction it is to be found in the fact that by the English

bill, if the people of Kansas had only agreed to become a

slaveholding State under the Lecompton Constitution, they

could have done so with 35,000 people, but if they insisted

on being a free State, as they had a right to do, then they

were to be punished by being kept out of the Union until

they had nearly three times that population.

I then said in my place in the Senate, as I now say

to you, that whenever Kansas

has population enough for a slave State she has population

enough for a free

State. I

have never yet given a vote, and I never intend to record

one, making an odious and unjust distinction between the

different States of this Union. I hold it to be a fundamental

principle in our republican form of government that all the

States of this Union, old

and new, free and slave, stand on an exact equality. Equality among the different States

is a cardinal principle on which all our institutions rest. Wherever, therefore, you make a

discrimination, saying to a slave State that it shall be

admitted with 35,000 inhabitants, and to a free State that it

shall not be admitted until it has 93,000 or 100,000

inhabitants, you are throwing the whole weight of the

Federal Government into the scale in favor of one class of

States against the other. Nor

would I on the other hand any sooner sanction the doctrine

that a free State could be

admitted into the Union

with 35,000 people, while a slave State was kept out until

it had 93,000. I have always

declared in the Senate my willingness, and I am willing now

to adopt the rule, that no Territory shall ever become a

State, until it has the requisite population for a member of

Congress, according to the then existing ratio.

But while I have always been, and am now willing to

adopt that general rule, I was not willing and would not

consent to make an exception of Kansas, as a

punishment for her obstinacy, in demanding the right to do

as she pleased in the formation of her Constitution.

It is proper that I should remark here, that my

opposition to the Lecompton Constitution did not rest upon

the peculiar position taken by Kansas on the subject

of slavery. I held then, and

hold now, that if the people of Kansas want a slave State,

it is their right to make one and be received into the Union

under it; if, on the contrary, they want a free State, it is

their right to have it, and no man should ever oppose their

admission because they ask it under the one or the other. I hold to that great principle of

self-government which asserts the right of every people to

decide for themselves the nature and character of the

domestic institutions and fundamental law under which they

are to live.

The

effort has been and is now being made in this State by

certain postmasters and other Federal office-holders, to

make a test of faith on the support of the English bill. These men are now making speeches

all over the State against me and in favor of Lincoln,

either directly or indirectly, because I would not sanction

a discrimination between slave and free States by voting

for the English bill. But while

that bill is made a test in Illinois for the

purpose of breaking up the Democratic organization in this

State, how is it in the other States? Go

to Indiana, and there you find English himself, the author

of the English bill, who is a candidate for re-election to

Congress, has been forced by public opinion to abandon his

own darling project, and to give a promise that he will vote

for the admission of Kansas at once, whenever she forms a

Constitution in pursuance of law, and ratifies it by a

majority vote of her people. Not

only is this the case with English himself, but I am

informed that every Democratic candidate for Congress in Indiana

takes the same ground. Pass to

Ohio,

and there you find that Groesbeck, and Pendleton, and Cox,

and all the other anti-Lecompton men who stood shoulder to

shoulder with me against the Lecompton Constitution, but

voted for the English bill, now repudiate it and take the

same ground that I do on that question.

So it is with the Joneses and others of Pennsylvania,

and so it is with every other Lecompton Democrat in the free States. They now abandon even the English

bill, and come back to the true platform which I proclaimed

at the time in the Senate, and upon which the Democracy of

Illinois now stand. And yet,

notwithstanding the fact, that every Lecompton and

anti-Lecompton Democrat in the free States has abandoned the

English bill, you are told that it is to be made a test upon

me, while the power and patronage of the Government are all

exerted to elect men to Congress in the other States who

occupy the same position with reference to it that I do. It seems that my political offense

consists in the fact that I first did not vote for the

English bill, and thus pledge myself to keep Kansas

out of the Union until she

has a population of 93,420, and then return home, violate

that pledge, repudiate the bill, and take the opposite

ground. If I had done this,

perhaps the Administration would now be advocating my

re-election, as it is that of the others who have pursued

this course. I did not choose

to give that pledge, for the reason that I did not intend to

carry out that principle. I

never will consent, for the sake of conciliating the frowns

of power, to pledge myself to do that which I do not intend

to perform. I now submit the

question to you as my constituency, whether I was not right,

first, in resisting the adoption of the Lecompton

Constitution; and secondly, in resisting the English bill. I repeat, that I opposed the

Lecompton Constitution because it was not the act and deed

of the people of Kansas,

and did not embody their will. I

denied the right of any power on earth, under our system of

Government, to force a Constitution on an unwilling people. There was a time when some men

could pretend to believe that the Lecompton Constitution

embodied the will of the people of Kansas, but that time

has passed. The question was

referred to the people of Kansas

under the English bill last August, and then, at a fair

election, they rejected the Lecompton Constitution by a vote

of from eight to ten against it to one in its favor.

Since it has been voted down by so overwhelming a

majority, no man can pretend that it was the act and deed of

that people. I submit the

question to you whether or not, if it had not been for me,

that Constitution would have been crammed down the throats

of the people of Kansas

against their consent. While at

least ninety-nine out of every hundred people here present,

agree that I was right in defeating that project, yet my

enemies use the fact that I did defeat it by doing right, to

break me down and put another man in the United States in my

place. The very men who

acknowledge that I was right in defeating Lecompton, now

form an alliance with Federal office-holders, professed

Lecompton men, to defeat me, because I did right.

My political opponent, Mr. Lincoln, has no hope on

earth, and has never dreamed that he had a chance of

success, were it not for the aid that he is receiving from

Federal office-holders, who are using their influence and

the patronage of the Government against me in revenge for my

having defeated the Lecompton Constitution.

What do you Republicans think of a political

organization that will try to make an unholy and unnatural

combination with its professed foes to beat a man merely

because he has done right? You

know such is the fact with regard to your own party.

You know that the ax of decapitation is suspended

over every man in office in Illinois, and the

terror of proscription is threatened every Democrat by the

present Administration, unless he supports the Republican

ticket in preference to my Democratic associates and myself. I could find an instance in the

postmaster of the city of Galesburgh,

and in every other postmaster in this vicinity, all of whom

have been stricken down simply because they discharged the

duties of their offices honestly, and supported the regular

Democratic ticket in this State in the right.

The Republican party is availing itself of every

unworthy means in the present contest to carry the election,

because its leaders know that if they let this chance slip

they will never have another, and their hopes of making this

a Republican

State

will be blasted forever.

Now,

let me ask you whether the country has any interest in

sustaining this organization, known as the Republican party. That party is unlike all other

political organizations in this country.

All other parties have been national in their

character—have avowed their principles alike in the slave

and free States, in Kentucky as well as Illinois,

in Louisiana as well as in

Massachusetts. Such was the case with the old

Whig party, and such was and is the case with the Democratic

party. Whigs and Democrats

could proclaim their principles boldly and fearlessly in the

North and in the South, in the East and in the West,

wherever the Constitution ruled and the American flag waved

over American soil.

But

now you have a sectional organization, a party which appeals

to the Northern section of the Union against the Southern, a

party which appeals to Northern passion, Northern pride,

Northern ambition, and Northern prejudices, against Southern

people, the Southern States, and Southern institutions. The leaders of that party hope

that they will be able to unite the Northern States in one

great sectional party, and inasmuch as the North is the

strongest section, that they will thus be enabled to out

vote, conquer, govern, and control the South.

Hence you find that they now make speeches

advocating principles and measures which cannot be defended

in any slaveholding

State, of this Union. Is

there a Republican residing in Galesburgh who can travel

into Kentucky and carry

his principles with him across the Ohio? What

Republican from Massachusetts

can visit the Old Dominion without leaving his principles

behind him when he crosses Mason and Dixon’s line?

Permit me to say to you in perfect good humor, but

in all sincerity, that no political creed is sound which

cannot be proclaimed fearlessly in every State of this Union where the Federal Constitution

is not the supreme law of the land. Not

only is this Republican party unable to proclaim its

principles alike in the North and in the South, in the free

States and in the slave States, but it cannot even proclaim

them in the same forms and give them the same strength and

meaning in all parts of the same State.

My friend Lincoln finds it extremely difficult to

manage a debate in the center part of the State, where there

is a mixture of men from the North and the South.

In the extreme Northern part of Illinois he can

proclaim as bold and radical Abolitionism as ever Giddings,

Lovejoy, or Garrison enunciated, but when he gets down a

little further South he claims that he is an old line Whig,

a disciple of Henry Clay, and declares that he still adheres

to the old line Whig creed, and has nothing whatever to do

with Abolitionism, or negro equality, or negro citizenship. I once before hinted this of Mr.

Lincoln in a public speech, and at Charleston he defied me

to show that there was any difference between his speeches

in the North and in the South, and that they were not in

strict harmony. I will now call

your attention to two of them, and you can then say whether

you would be apt to believe that the same man ever uttered

both. In a speech in reply to

me at Chicago

in July last, Mr. Lincoln,

in speaking of the equality of the negro with the white man,

used the following language:

“I

should like to know, if taking this old Declaration of

Independence, which declares that all men are equal upon

principle, and making exceptions to it, where will it stop? If one man says it does not mean a

negro, why may not another man say it does not mean another

man? If the Declaration is not

the truth, let us get the statute book in which we find it

and tear it out. Who is so bold

as to do it? If it is not true,

let us tear it out.”

You

find that Mr. Lincoln there proposed that if the doctrine of

the Declaration of Independence, declaring all men to be

born equal, did not include the negro and put him on an

equality with the white man, that we should take the statute

book and tear it out. He there

took the ground that the negro race is included in the

Declaration of Independence as the equal of the white race,

and that there could be no such thing as a distinction in

the races, making one superior and the other inferior. I read now from the same speech:

“My

friends [he says], I have detained you about as long as I

desire to do, and I have only to say let us discard all this

quibbling about this man and the other man—this race and

that race and the other race being inferior, and therefore

they must be placed in an inferior position, discarding our

standard that we have left us. Let

us discard all these things, and unite as one people

throughout this land, until we shall once more stand up

declaring that all men are created equal.”

[“That’s

right,” etc.]

Yes,

I have no doubt that you think it is right, but the Lincoln men down in Coles, Tazewell

and Sangamon counties do

not think it is right. In the

conclusion of the same speech, talking to the Chicago

Abolitionists, he said: “I leave you, hoping that the lamp

of liberty will burn in your bosoms until there shall no

longer be a doubt that all men are created free and equal.” [“Good, good.”] Well,

you say good to that, and you are going to vote for Lincoln

because he holds that doctrine. I

will not blame you for supporting him on that ground, but I

will show you in immediate contrast with that doctrine, what

Mr. Lincoln said down in Egypt in order to get votes in that

locality where they do not hold to such a doctrine.

In a joint discussion between Mr. Lincoln and

myself, at Charleston,

I think, on the 18th of last month, Mr. Lincoln, referring

to this subject, used the following language:

“I

will say then, that I am not nor never have been in favor of

bringing about in any way the social and political equality

of the white and black races; that I am not nor never have

been in favor of making voters of the free negroes, or

jurors, or qualifying them to hold office, or having them to

marry with white people. I will

say in addition, that there is a physical difference between

the white and black races, which, I suppose, will forever

forbid the two races living together upon terms of social

and political equality, and inasmuch as they cannot so live,

that while they do remain together, there must be the

position of superior and inferior, that I as much as any

other man am in favor of the superior position being

assigned to the white man.”

[“Good

for Lincoln.”]

Fellow-citizens,

here you find men hurraing for Lincoln and saying that

he did right, when in one part of the State he stood up for

negro equality, and in another part for political effect,

discarded the doctrine and declared that there always must

be a superior and inferior race. Abolitionists

up north are expected and required to vote for Lincoln

because he goes for the equality of the races, holding that

by the Declaration of Independence the white man and the

negro were created equal, and endowed by the Divine law with

that equality, and down south he tells the old Wings, the

Kentuckians, Virginians, and Tennesseeans, that there is a

physical difference in the races, making one superior and

the other inferior, and that he is in favor of maintaining

the superiority of the white race over the negro.

Now, how can you reconcile those two positions of

Mr. Lincoln? He is to be voted for in the south

as a pro-slavery man, and he is to be voted for in the north

as an Abolitionist. Up here he

thinks it is all nonsense to talk about a difference between

the races, and says that we must “discard all quibbling

about this race and that race and the other race being

inferior, and therefore they must be placed in an inferior

position.” Down south he makes

this “quibble” about this race and that race and the other

race being inferior as the creed of his party, and declares

that the negro can never be elevated to the position of the

white man. You find that his

political meetings are called by different names in

different counties in the State. Here

they are called Republican meetings, but in old Tazewell,

where Lincoln made a speech

last Tuesday, he did not address a Republican

meeting, but a “grand rally of the Lincoln men.” There are very few Republicans

there, because Tazewell county is filled with old Virginians

and Kentuckians, all of whom are ‘Whigs or Democrats, and if

Mr. Lincoln had called an Abolition or Republican meeting

there, he would not get many votes. Go

down

into Egypt

and you find that he and his party are operating under an

alias there, which his friend Trumbull has given them, in

order that they may cheat the people. When

I was down in Monroe county a few weeks ago addressing the

people, I saw handbills posted announcing that Mr. Trumbull

was going to speak in behalf of Lincoln, and what do you

think the name of his party was there?

Why the “Free Democracy.” Mr.

Trumbull and Mr. Jehu Baker were announced to address the

Free Democracy of Monroe county, and the bill was signed

“Many Free Democrats.” The

reason that Lincoln and his party adopted the name of “Democracy”

down there was because Monroe

county has always been an old-fashioned Democratic county,

and hence it was necessary to make the people believe that

they were Democrats, sympathized with them, and were

fighting for Lincoln

as Democrats. Come up to

Springfield, where Lincoln now lives and always has lived,

and you find that the Convention of his party which

assembled to nominate candidates for Legislature, who are

expected to vote for him if elected, dare not adopt the name

of Republican, but assembled under the title of “all opposed

to the Democracy.” Thus you

find that Mr. Lincoln’s creed cannot travel through even one

half of the counties of this State, but that it changes its

hues and becomes lighter and lighter, as it travels from the

extreme north, until it is nearly white, when it reaches the

extreme south end of the State. I

ask you, my friends, why cannot Republicans avow their

principles alike everywhere? I

would despise myself if I thought that I was procuring your

votes by concealing my opinions, and by avowing one set of

principles in one part of the State, and a different set in

another part. If I do not truly

and honorably represent your feelings and principles, then I

ought not to be your Senator; and I will never conceal my

opinions, or modify or change them a hair’s breadth in order

to get votes. I tell you that

this Chicago doctrine of Lincoln’s—declaring

that

the negro and the white man are made equal by the

Declaration of Independence and by Divine Providence—is a

monstrous heresy. The signers

of the Declaration of Independence never dreamed of the

negro when they were writing that document.

They referred to white men, to men of European

birth and European descent, when they declared the equality

of all men. I see a gentleman

there in the crowd shaking his head. Let

me remind him that when Thomas Jefferson wrote that

document, he was the owner, and so continued until his

death, of a large number of slaves. Did

he intend to say in that Declaration, that his negro slaves,

which he held and treated as property, were created his

equals by Divine law, and that he was violating the law of

God every day of his life by holding them as slaves?

It must be borne in mind that when that Declaration

was put forth, every one of the thirteen Colonies were

slaveholding Colonies, and every man who signed that

instrument represented a slave holding constituency.

Recollect, also, that no one of them emancipated

his slaves, much less put them on an equality with himself,

after he signed the Declaration. On

the contrary, they all continued to hold their negroes as

slaves during the revolutionary war. Now,

do you believe—are you willing to have it said—that every

man who signed the Declaration of Independence declared the

negro his equal, and then was hypocrite enough to continue

to hold him as a slave, in violation of what he believed to

be the Divine law? And yet when

you say that the Declaration of Independence includes the

negro, you charge the signers of it with hypocrisy.

I

say to you, frankly, that in my opinion, this Government was

made by our fathers on the white basis.

It was made by white men for the benefit of white men

and their posterity forever, and was intended to be

administered by white men in all time to come.

But while I hold that under our Constitution and

political system the negro is not a citizen, cannot be a

citizen, and ought not to be a citizen, it does not follow

by any means that he should be a slave.

On the contrary it does follow that the negro, as an

inferior race, ought to possess every right, every

privilege, every immunity which he can safely exercise

consistent with the safety of the society in which he lives. Humanity requires, and

Christianity commands, that you shall extend to every

inferior being, and every dependent being, all the

privileges, immunities and advantages which can be granted

to them consistent with the safety of society.

If you ask me the nature and extent of these

privileges, I answer that that is a question which the

people of each State must decide for themselves.

Illinois

has decided that question for herself.

We have said that in this State the negro shall not

be a slave, nor shall he be a citizen.

Kentucky

holds a different doctrine. New York holds one different from

either, and Maine

one different from all. Virginia,

in her policy on this question, differs in many respects

from the others, and so on, until there is hardly two States

whose policy is exactly alike in regard to the relation of

the white man and the negro. Nor

can you reconcile them and make them alike.

Each State must do as it pleases.

Illinois had as

much right to adopt the policy which we have on that subject

as Kentucky

had to adopt a different policy. The

great principle of this Government is, that each State has

the right to do as it pleases on all these questions, and no

other State, or power on earth has the right to interfere

with us, or complain of us merely because our system differs

from theirs. In the Compromise

Measures of 1850, Mr. Clay declared that this great

principle ought to exist in the Territories as well as in

the States, and I reasserted his doctrine in the Kansas and Nebraska bill in 1854.

But

Mr. Lincoln cannot be made to understand, and those who are

determined to vote for him, no matter whether he is a

pro-slavery man in the south and a negro equality advocate

in the north, cannot be made to understand how it is that in

a Territory the people can do as they please on the slavery

question under the Dred Scott decision.

Let us see whether I cannot explain it to the

satisfaction of all impartial men. Chief

Justice

Taney has said in his opinion in the Dred Scott case, that a

negro slave being property, stands on an equal footing with

other property, and that the owner may carry them into United States

territory the same as he does other property.

Suppose any two of you, neighbors, should conclude

to go to Kansas,

one carrying $100,000 worth of negro slaves and the other

$100,000 worth of mixed merchandise, including quantities of

liquors. You both agree that

under that decision you may carry your property to Kansas,

but when you get it there, the merchant who is possessed of

the liquors is met by the Maine liquor law, which prohibits

the sale or use of his property, and the owner of the slaves

is met by equally unfriendly legislation, which makes his

property worthless after he gets it there.

What is the right to carry your property into the

Territory worth to either, when unfriendly legislation in

the Territory renders it worthless after you get it there? The slaveholder when he gets his

slaves there finds that there is no local law to protect him

in holding them, no slave code, no police regulation

maintaining and supporting him in his right, and he

discovers at once that the absence of such friendly

legislation excludes his property from the Territory, just

as irresistibly as if there was a positive Constitutional

prohibition excluding it. Thus

you find it is with any kind of property in a Territory, it

depends for its protection on the local and municipal law. If the people of a Territory want

slavery, they make friendly legislation to introduce it, but

if they do not want it, they withhold all protection from

it, and then it cannot exist there. Such

was the view taken on the subject by different Southern men

when the Nebraska

bill passed. See the speech of

Mr. Orr, of South

Carolina, the present Speaker of

the House of Representatives of Congress, made at that time,

and there you will find this whole doctrine argued out at

full length. Read the speeches

of other Southern Congressmen, Senators and Representatives,

made in 1854, and you will find that they took the same view

of the subject as Mr. Orr—that slavery could never be forced

on a people who did not want it. I

hold that in this country there is no power on the face of

the globe that can force any institution on an unwilling

people. The great fundamental

principle of our Government is that the people of each State

and each Territory shall be left perfectly free to decide

for themselves what shall be the nature and character of

their institutions. When this

Government was made, it was based on that principle.

At the time of its formation there were twelve slaveholding States

and one free State in this

Union.

Suppose this doctrine of Mr. Lincoln and the

Republicans, of uniformity of laws of all the States on the

subject of slavery, had prevailed; suppose Mr. Lincoln

himself had been a member of the Convention which framed the

Constitution, and that he had risen in that august body, and

addressing the father of his country, had said as he did at

Springfield:

“A

house divided against itself cannot stand.

I believe this Government cannot endure permanently

half slave and half free. I do

not expect the Union to be

dissolved—I do not expect the house to fall, but I do expect

it will cease to be divided. It

will become all one thing or all the other.”

What

do you think would have been the result? Suppose

he had made that Convention believe that doctrine and they

had acted upon it, what do you think would have been the

result? Do you believe that the

one free State

would have outvoted the twelve slaveholding States, and thus

abolish slavery? On the

contrary, would not the twelve slaveholding States have

outvoted the one free State,

and under his doctrine have fastened slavery by an

irrevocable Constitutional provision upon every inch of the

American

Republic?

Thus you see that the doctrine

he now advocates, if proclaimed at the beginning of the

Government, would have established slavery every where

throughout the American continent, and are you willing, now

that we have the majority section, to exercise a power which

we never would have submited to when we were in the

minority? If the Southern

States had attempted to control our institutions, and make

the States all slave when they had the power, I ask would

you have submitted to it? If

you would not, are you willing now, that we have become the

strongest under that great principle of self-government that

allows each State to do as it pleases, to attempt to control

the Southern institutions? Then,

my

friends, I say to you that there is but one path of peace in

this Republic, and that is to administer this Government as

our fathers made it, divided into free and slave States,

allowing each State to decide for itself whether it wants

slavery or not. If Illinois will settle the slavery

question for herself, and mind her own business and let her

neighbors alone, we will be at peace with Kentucky, and every

other Southern State. If every

other State in the Union will do the same there will be

peace between the North and the South, and in the whole Union.

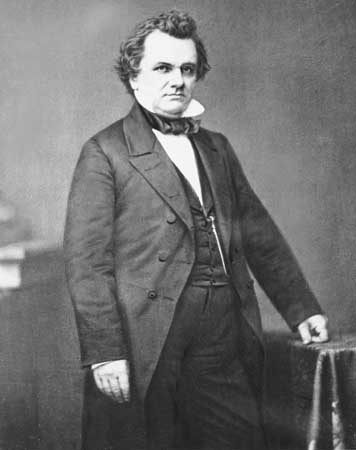

MR. LINCOLN'S

REPLY.

MY FELLOW-CITIZENS: A very large

portion of the speech which Judge Douglas has addressed to

you has previously been delivered and put in print.

I do not mean that for a hit upon the Judge at all.

If I had not been interrupted, I

was going to say that such an answer as I was able to make

to a very large portion of it, had already been more than

once made and published. There

has been an opportunity afforded to the public to see our

respective views upon the topics discussed in a large

portion of the speech which he has just delivered.

I make these remarks for the purpose of excusing

myself for not passing over the entire ground that the Judge

has traversed. I however desire

to take up some of the points that he has attended to, and

ask your attention to them, and I shall follow him backwards

upon some notes which I have taken, reversing the order by

beginning where he concluded.

The

Judge has alluded to the Declaration of Independence, and

insisted that negroes are not included in that Declaration;

and that it is a slander upon the framers of that

instrument, to suppose that negroes were meant therein; and

he asks you: Is it possible to believe that Mr. Jefferson,

who penned the immortal paper, could have supposed himself

applying the language of that instrument to the negro race,

and yet held a portion of that race in slavery?

Would he not at once have freed them? I

only have to remark upon this part of the Judge’s speech

(and that, too, very briefly, for I shall not detain myself,

or you, upon that point for any great length of time), that

I believe the entire records of the world, from the date of

the Declaration of Independence

up to within three years ago, may be searched in vain for

one single affirmation, from one single man, that the negro

was not included in the Declaration of Independence; I think

I may defy Judge Douglas to show that he ever said so, that

Washington

ever said so, that any President ever said so, that any

member of Congress ever said so, or that any living man upon

the whole earth ever said so, until the necessities of the

present policy of the Democratic party, in regard to

slavery, had to invent that affirmation.

And I will remind Judge Douglas and this audience,

that while Mr. Jefferson was the owner of slaves, as

undoubtedly he was, in speaking upon this very subject, he

used the strong language that “he trembled for his country

when he remembered that God was just;” and I will offer the

highest premium in my power to Judge Douglas if he will show

that he, in all his life, ever uttered a sentiment at all

akin to that of Jefferson.

The

next thing to which I will ask your attention is the Judge’s

comments upon the fact, as he assumes it to be, that we

cannot call our public meetings as Republican meetings; and

he instances Tazewell county as one of the places where the

friends of Lincoln have called a public meeting and have not

dared to name it a Republican meeting.

He instances Monroe

county as another where Judge Trumbull and Jehu Baker

addressed the persons whom the Judge assumes to be the

friends of Lincoln,

calling them the “Free Democracy.” I

have the honor to inform Judge Douglas that he spoke in that

very county

of Tazewell

last Saturday, and I was there on Tuesday last, and when he

spoke there he spoke under a call not venturing to use the

word “Democrat.” [Turning to

Judge Douglas.] What think you

of this?

So

again, there is another thing to which I would ask the

Judge’s attention upon this subject. In

the contest of 1856 his party delighted to call themselves

together as the “National Democracy,” but now, if there

should be a notice put up any where for a meeting of the

“National Democracy,” Judge Douglas and his friends would

not come. They would not

suppose themselves invited. They

would

understand that it was a call for those hateful postmasters

whom he talks about.

Now

a few words in regard to these extracts from speeches of

mine, which Judge Douglas has read to you, and which he

supposes are in very great contrast to each other.

Those speeches have been before the public for a

considerable time, and if they have any inconsistency in

them, if there is any conflict in them, the public have been

able to detect it. When the

Judge says, in speaking on this subject, that I make

speeches of one sort for the people of the northern end of

the State, and of a different sort for the southern people,

he assumes that I do not understand that my speeches will be

put in print and read north and south.

I knew all the while that the speech that I made at Chicago, and the one I made at Jonesboro and the one at Charleston,

would all be put in print and all the reading and

intelligent men in the community would see them and know all

about my opinions. And I have

not supposed, and do not now suppose, that there is any

conflict whatever between them. But

the Judge will have it that if we do not confess that there

is a Sort of inequality between the white and black races,

which justifies us in making them slaves, we must, then,

insist that there is a degree of equality that requires us

to make them our wives. Now, I

have all the while taken a broad distinction in regard to

that matter; and that is all there is in these different

speeches which he arrays here, and the entire reading of

either of the speeches will show that that distinction was

made. Perhaps by taking two

parts of the same speech, he could have got up as much of a

conflict as the one he has found. I

have all the while maintained, that in so far as it should

be insisted that there was an equality between the white and

black races that should produce a perfect social and

political equality, it was an impossibility.

This you have seen in my printed speeches, and with

it I have said, that in their right to “life, liberty and

the pursuit of happiness,” as proclaimed in that old

Declaration, the inferior races are our equals.

And these declarations I have constantly made in

reference to the abstract moral question, to contemplate and

consider when we are legislating about any new country which

is not already cursed with the actual presence of the

evil—slavery. I have, never

manifested any impatience with the necessities that spring

from the actual presence of black people amongst us, and the

actual existence of slavery amongst us where it does already

exist; but I have insisted that, in legislating for new

countries, where it does not exist, there is no just rule

other than that of moral and abstract right! With

reference to those new countries, those maxims as to the

right of a people to “life, liberty and the pursuit of

happiness,” were the just rules to be constantly referred

to. There is no

misunderstanding this, except by men interested to

misunderstand it. I take it

that I have to address an intelligent and reading community,

who will peruse what I say, weigh it, and then judge whether

I advance improper or unsound views, or whether I advance

hypocritical, and deceptive, and contrary views in different

portions of the country. I

believe myself to be guilty of no such thing as the latter,

though, of course, I cannot claim that I am entirely free

from all error in the opinions I advance.

The

Judge has also detained us awhile in regard to the

distinction between his party and our party.

His he assumes to be a national party—ours a

sectional one. He does this in

asking the question whether this country has any interest in

the maintenance of the Republican party?

He assumes that our party is altogether

sectional—that the party to which he adheres is national;

and the argument is, that no party can be a rightful

party—can be based upon rightful principles—unless it can

announce its principles every where. I

presume that Judge Douglas could not go into Russia and

announce the doctrine of our national Democracy; he could

not denounce the doctrine of kings and emperors and

monarchies in Russia; and it may be true of this country,

that in some places we may not be able to proclaim a

doctrine as clearly true as the truth of Democracy, because

there is a section so directly opposed to it that they will

not tolerate us in doing so. Is

it the true test of the soundness of a doctrine, that in

some places people won’t let you proclaim it?

Is that the way to test the truth of any doctrine? Why, I understood that at one time

the people of Chicago

would not let Judge Douglas preach a certain favorite

doctrine of his. I commend to

his consideration the question, whether he takes that as a

test of the unsoundness of what he wanted to preach.

There

is another thing to which I wish to ask attention for a

little while on this occasion. What

has always been the evidence brought forward to prove that

the Republican party is a sectional party?

The main one was that in the Southern portion of

the Union the people did

not let the Republicans proclaim their doctrines amongst

them. That has been the main

evidence brought forward—that they had no supporters, or

substantially none, in the slave States.

The South have not taken hold of our principles as

we announce them; nor does Judge Douglas now grapple with

those principles. We have a

Republican State Platform, laid down in Springfield in June

last, stating our position all the way through the questions

before the country. We are now

far advanced in this canvass. Judge

Douglas and I have made perhaps forty speeches apiece, and

we have now for the fifth time met face to face in debate,

and up to this day I have not found either Judge Douglas or

any friend of his taking hold of the Republican platform or

laying his finger upon anything in it that is wrong.

I ask you all to recollect that.

Judge Douglas turns away from the platform of

principles to the fact that he can find people somewhere who

will not allow us to announce those principles.

If he had great confidence that our principles were

wrong, he would take hold of them and demonstrate them to be

wrong. But he does not do so. The only evidence he has of their

being wrong is in the fact that there are people who won’t

allow us to preach them. I ask

again is that the way to test the soundness of a doctrine?

I

ask his attention also to the fact that by the rule of

nationality he is himself fast becoming sectional.

I ask his attention to the fact that his speeches

would not go as current now south of the Ohio

river as they have formerly gone there.

I ask his attention to the fact that he felicitates

himself to-day that all the Democrats of the free States are

agreeing with him, while he omits to tell us that the

Democrats of any slave State agree with him.

If he has not thought of this, I commend to his

consideration the evidence in his own declaration, on this

day, of his becoming sectional too. I

see it rapidly approaching. Whatever

may be the result of this ephemeral contest between Judge

Douglas and myself, I see the day rapidly approaching when

his pill of sectionalism, which he has been thrusting down

the throats of Republicans for years past, will be crowded

down his own throat.

Now

in regard to what Judge Douglas said (in the beginning of

his speech) about the Compromise of 1850, containing the

principle of the Nebraska bill, although I have often

presented my views upon that subject, yet as I have not done

so in this canvass, I will, if you please, detain you a

little with them. I have always

maintained, so far as I was able, that there was nothing of

the principle of the Nebraska

bill in the Compromise of 1850 at all—nothing whatever. Where can you find the principle

of the Nebraska

bill in that Compromise? If any

where, in the two pieces of the Compromise organizing the

Territories of New Mexico and Utah.

It was expressly provided in these two acts, that,

when they came to be admitted into the Union,

they should be admitted with or without slavery, as they

should choose, by their own Constitutions.

Nothing was said in either of those acts as to what

was to be done in relation to slavery during the territorial

existence of those Territories, while Henry Clay constantly

made the declaration (Judge Douglas recognizing him as a

leader) that, in his opinion, the old Mexican laws would

control that question during the territorial existence, and

that these old Mexican laws excluded slavery.

How can that be used as a principle for declaring

that during the territorial existence as well as at the time

of framing the Constitution, the people, if you please,

might have slaves if they wanted them?

I am not discussing the question whether it is right

or wrong; but how are the New Mexican and Utah

laws patterns for the Nebraska

bill? I maintain that the

organization of Utah and New Mexico

did not establish a general principle at all.

It had no feature of establishing a general

principle. The acts to which I

have referred were a part of a general system of

Compromises. They did not lay

down what was proposed as a regular policy for the

Territories; only an agreement in this particular case to do

in that way, because other things were done that were to be

a compensation for it. They

were allowed to come in in that shape, because in another

way it was paid for—considering that as a part of that

system of measures called the Compromise of 1850, which

finally included half a dozen acts. It

included

the admission of California

as a free State, which was

kept out of the Union for

half a year because it had formed a free Constitution. It included the settlement of the

boundary of Texas, which had been undefined before, which

was in itself a slavery question; for, if you pushed the

line farther west, you made Texas larger, and made more

slave Territory; while, if you drew the line toward the

east, you narrowed the boundary and diminished the domain of

slavery, and by so much increased free Territory.

It included the abolition of the slave-trade in the

District of

Columbia. It

included the passage of a new Fugitive Slave law.

All these things were put together, and though

passed in separate acts, were nevertheless in legislation

(as the speeches at the time will show), made to depend upon

each other. Each got votes,

with the understanding that the other measures were to pass,

and by this system of Compromise, in that series of

measures, those two bills —the New Mexico and Utah

bills—were passed; and I say for that reason they could not

be taken as models, framed upon their own intrinsic

principle, for all future Territories.

And I have the evidence of this in the fact that

Judge Douglas, a year afterward, or more than a year

afterward, perhaps, when he first introduced bills for the

purpose of framing new Territories, did not attempt to

follow these bills of New Mexico

and Utah; and even when he introduced this Nebraska bill, I think

you will discover that he did not exactly follow them. But I do not wish to dwell at

great length upon this branch of the discussion.

My own opinion is, that a thorough investigation

will show most plainly that the New

Mexico and Utah

bills were part of a system of Compromise, and not designed

as patterns for future territorial legislation; and that

this Nebraska

bill did not follow them as a pattern at all.

The

Judge tells, in proceeding, that he is opposed to making any

odious distinctions between free and slave States.

I am altogether unaware that the Republicans are in

favor of making any odious distinctions between the free and

slave States. But there still

is a difference, I think, between Judge Douglas and the

Republicans in this. I suppose

that the real difference between Judge Douglas and his

friends, and the Republicans on the contrary, is, that the

Judge is not in favor of making any difference between

slavery and liberty—that he is in favor of eradicating, of

pressing out of view, the questions of preference in this

country for free or slave institutions; and consequently

every sentiment he utters discards the idea that there is

any wrong in slavery. Every

thing that emanates from him or his coadjutors in their

course of policy, carefully excludes the thought that there

is any thing wrong in slavery. Al! their arguments, if you will

consider them, will be seen to exclude the thought that

there is any thing whatever wrong in slavery.

If you will take the Judge’s speeches, and select

the short and pointed sentences expressed by him—as his

declaration that he “don’t care whether slavery is voted up

or down”—you will see at once that this is perfectly

logical, if you do not admit that slavery is wrong.

If you do admit that it is wrong, Judge Douglas

cannot logically say he don’t care whether a wrong is voted

up or voted down. Judge Douglas

declares that if any community want slavery they have a

right to have it. He can say

that logically, if he says that there is no wrong in

slavery; but if you admit that there is a wrong in it, he

cannot logically say that any body has a right to do wrong. He insists that, upon the score of

equality, the owners of slaves and owners of property—of

horses and every other sort of property—should be alike and

hold them alike in a new Territory. That

is perfectly logical, if the two species of property are

alike and are equally founded in right.

But if you admit that one of them is wrong, you

cannot institute any equality between right and wrong. And from this difference of

sentiment—the belief on the part of one that the institution

is wrong, and a policy springing from that belief which

looks to the arrest of the enlargement of that wrong; and

this other sentiment, that it is no wrong, and a policy

sprung from that sentiment which will tolerate no idea of

preventing that wrong from growing larger, and looks to

there never being an end of it through all the existence of

things,—arises the real difference between Judge Douglas and

his friends on the one hand, and the Republicans on the

other. Now, I confess myself as

belonging to that class in the country who contemplate

slavery as a moral, social and political evil, having due

regard for its actual existence amongst us and the

difficulties of getting rid of it in any satisfactory way,

and to all the Constitutional obligations which have been

thrown about it; but, nevertheless, desire a policy that

looks to the prevention of it as a wrong, and looks

hopefully to the time when as a wrong it may come to an end.

Judge

Douglas has again, for, I believe, the fifth time, if not

the seventh, in my presence, reiterated his charge of a

conspiracy or combination between the National Democrats and

Republicans. What evidence

Judge Douglas has upon this subject I know not, inasmuch as

he never favors us with any. I

have said upon a former occasion, and I do not choose to

suppress it now, that I have no objection to the division in

the Judge’s party. He got it up

himself. It was all his and

their work. He had, I think, a

great deal more to do with the steps that led to the

Lecompton Constitution than Mr. Buchanan had; though at

last, when they reached it, they quarreled over it, and

their friends divided upon it. I

am very free to confess to Judge Douglas that I have no

objection to the division; but I defy the Judge to show any

evidence that I have in any way promoted that division,

unless he insists on being a witness himself in merely

saying so. I can give all fair

friends of Judge Douglas

here to understand exactly the view that Republicans take in

regard to that division. Don’t

you remember how two years ago the opponents of the

Democratic party were divided between Fremont and Fillmore? I guess you do.

Any Democrat who remembers that division, will

remember also that he was at the time very glad of it, and

then he will be able to see all there is between the

National Democrats and the Republicans.

What we now think of the two divisions of Democrats,

you then thought of the Fremont and Fillmore divisions. That is all there is of it.

But,

if the Judge continues to put forward the declaration that

there is an unholy and unnatural alliance between the

Republican and the National Democrats, I now want to enter

my protest against receiving him as an entirely competent

witness upon that subject. I

want to call to the Judge’s attention an attack he made upon

me in the first one of these debates, at Ottawa, on the 21st of

August. In order to fix extreme

Abolitionism upon me, Judge Douglas read a set of

resolutions which he declared had been passed by a

Republican State Convention, in October, 1854, at Springfield, Illinois, and he

declared I had taken part in that Convention.

It turned out that although a few men calling

themselves an anti-Nebraska State Convention had sat at Springfield

about that time, yet neither did I take any part in it, nor

did it pass the resolutions or any such resolutions as Judge

Douglas read. So apparent had

it become that the resolutions which he read had not been

passed at Springfield

at all, nor by a State Convention in which I had taken part,

that seven days afterward, at Freeport, Judge Douglas

declared that he had been misled by Charles H.

Lanphier, editor of the State Register,

and Thomas L. Harris, member of

Congress in that District, and he promised in that speech

that when he went to Springfield

he would investigate the matter. Since

then Judge Douglas has been to Springfield, and I presume

has made the investigation; but a month has passed since he

has been there, and so far as I know, he has made no report

of the result of his investigation. I

have waited as I think sufficient time for the report of

that investigation, and I have some curiosity to see and

hear it. A fraud—an absolute

forgery was committed, and the perpetration of it was traced

to the three—Lanphier, Harris and Douglas. Whether it can be narrowed in any

way so as to exonerate any one of them, is what Judge

Douglas’s report would probably show.

It

is true that the set of resolutions read by Judge Douglas

were published in the Illinois State Register

on the l6th of October, 1854, as being the resolutions of an

anti-Nebraska Convention, which had sat in that same month

of October, at Springfield. But

it is also true that the publication in the Register

was a forgery then, and the question is still behind, which

of the three, if not all of them, committed that forgery? The idea that it was done by

mistake, is absurd. The article

in the Illinois State Register contains

part of the real proceedings of that Springfield Convention,

showing that the writer of the article had the real

proceedings before him, and purposely threw out the genuine

resolutions passed by the Convention, and fraudulently

substituted the others. Lanphier

then, as now, was the editor of the Register,

so that there seems to be but little room for his escape. But then it is to be borne in mind

that Lanphier had less interest in the object of that

forgery than either of the other two. The

main

object of that forgery at that time was to beat Yates and

elect Harris to Congress, and that object was known to be

exceedingly dear to Judge Douglas

at that time. Harris and

Douglas were both in Springfield

when the Convention was in session, and although they both

left before the fraud appeared in the Register,

subsequent events show that they have both had their eyes

fixed upon that Convention.

The

fraud having been apparently successful upon the occasion,

both Harris and Douglas have more than once since then been

attempting to put it to new uses. As

the fisherman’s wife, whose drowned husband was brought home

with his body full of eel, said when she was asked, ‘”What

was to be done with him?” “Take the eels out and

set him again;” so Harris and Douglas have shown a

disposition to take the eels out of that stale fraud by

which they gained Harris’s election, and set the fraud again

more than once. On the 9th of

July, 1856, Douglas attempted a repetition of it upon Trumbull on the floor of the Senate

of the United

States, as will appear

from the appendix of the Congressional Globe

of that date.

On

the 9th of August, Harris attempted it again upon Norton in

the House of Representatives, as will appear by the same

documents—the appendix to the Congressional

Globe of that date. On

the 21st of August last, all three—Lanphier, Douglas and

Harris—reattempted it upon me at Ottawa.

It has been clung to .and played out again and

again as an exceedingly high trump by this blessed trio. And now that it has been

discovered publicly to be a fraud, we find that Judge

Douglas manifests no surprise at it at all.

He makes no complaint of Lanphier, who must have

known it to be a fraud from the beginning.

He, Lanphier and Harris, are just as cozy now, and

just as active in the concoction of new schemes as they were

before the general discovery of this fraud.

Now all this is very natural if they are all alike

guilty in that fraud, and it is very unnatural if any one of

them is innocent. Lanphier

perhaps insists that the rule of honor among thieves does

not quite require him to take all upon himself, and

consequently my friend Judge Douglas finds it difficult to

make a satisfactory report upon his investigation.

But meanwhile the three are agreed that each is “a most honorable man.”

Judge

Douglas requires an indorsement of his truth and honor by a

re-election to the United States Senate, and he makes and

reports against me and against Judge Trumbull, day after

day, charges which we know to be utterly untrue, without for

a moment seeming to think that this one unexplained fraud,

which he promised to investigate, will be the least drawback

to his claim to belief. Harris

ditto. He asks a re-election to

the lower House of Congress without seeming to remember at

all that he is involved in this dishonorable fraud!

The Illinois State Register,

edited by Lanphier, then, as now, the central organ of both

Harris and Douglas, continues to din the public ear with

this assertion without seeming to suspect that these

assertions ate at all lacking in title to belief.

After

all, the question still recurs upon us, how did that fraud

originally get into the State Register? Lanphier then, as now, was the

editor of that paper. Lanphier

knows. Lanphier cannot be

ignorant of how and by whom it was originally concocted. Can he be induced to tell, or if

he has told, can Judge Douglas be induced to tell how it

originally was concocted? It

may be true that Lanphier insists that the two men for whose

benefit it was originally devised, shall at least bear their

share of it! How that is, I do

not know, and while it remains unexplained, I hope to be

pardoned if I insist that the mere fact of Judge Douglas

making charges against Trumbull and myself is not quite

sufficient evidence to establish them!

While

we were at Freeport,

in one of these joint discussions, I answered certain

interrogatories which Judge Douglas had propounded to me,

and there in turn propounded some to him, which he in a sort

of way answered. The third one

of these interrogatories I have with me and wish now to make

some comments upon it. It was

in these words: “If the Supreme Court of the United States

shall decide that the States cannot exclude slavery from

their limits, are you in favor of acquiescing in, adhering

to and following such decision, as a rule of political

action ?”

To

this interrogatory Judge Douglas made no answer in any just

sense of the word. He contented

himself with sneering at the thought that it was possible

for the Supreme Court ever to make such a decision.

He sneered at me for propounding the interrogatory. I had not propounded it without

some reflection, and I wish now to address to this audience

some remarks upon it.

In

the second clause of the sixth article, I believe it is, of

the Constitution of the United States, we find the following

language: “This Constitution and the laws of the United

States which shall be made in pursuance thereof; and all

treaties made, or which shall be made under the authority of

the United States, shall be the supreme law of the land; and

the judges in every State shall be bound thereby, any thing

in the Constitution or laws of any State to the contrary

notwithstanding.”

The

essence of the Dred Scott case is compressed into the

sentence which I will now read: “Now, as we have already

said in an earlier part of this opinion, upon a different

point, the right of property in a slave is distinctly and

expressly affirmed in the Constitution.”

I repeat it, “The right of property in

a slave is distinctly and expressly affirmed in the

Constitution!” What is it

to be “affirmed” in the Constitution?

Made firm in the Constitution—so made that it

cannot be separated from the Constitution without breaking

the Constitution—durable as the Constitution, and part of

the Constitution. Now,

remembering the provision of the Constitution which I have

read, affirming that that instrument is the supreme law of

the land; that the Judges of every State shall be bound by

it, any law or Constitution of any State to the contrary

notwithstanding; that the right of property in a slave is

affirmed in that Constitution, is made, formed into, and

cannot be separated from it without breaking it; durable as

the instrument; part of the instrument;—what follows as a

short and even syllogistic argument from it?

I think it follows, and I submit to the

consideration of men capable of arguing, whether as I state

it, in syllogistic form, the argument has any fault in it?

Nothing

in the Constitution or laws of any State can destroy a right

distinctly and expressly affirmed in the Constitution of the

United

States.

The

right of property in a slave is distinctly and expressly

affirmed in the Constitution of the United States.

Therefore,

nothing in the Constitution or laws of any State can destroy

the right of property in a slave.

I

believe that no fault can be pointed out in that argument;

assuming the truth of the premises, the conclusion, so far

as I have capacity at all to understand it, follows

inevitably. There is a fault in

it as I think, but the fault is not in the reasoning; but

the falsehood in fact is a fault of the premises.

I believe that the right of property in a slave is not distinctly and expressly affirmed in

the Constitution, and Judge Douglas thinks it is.

I believe that the Supreme Court and the advocates

of that decision may search in vain for the place in the

Constitution where the right of a slave is distinctly and

expressly affirmed. I say,

therefore, that I think one of the premises is not true in

fact. But it is true with Judge

Douglas. It is true with the

Supreme Court who pronounced it. They

are

estopped from denying it, and being estopped from denying

it, the conclusion follows that the Constitution of the United States

being the supreme law, no constitution or law can interfere

with it. It being affirmed in

the decision that the right of property in a slave is

distinctly and expressly affirmed in the Constitution, the

conclusion inevitably follows that no State law or

constitution can destroy that right. I

then say to Judge Douglas and to all others, that I think it

will take a better answer than a sneer to show that those

who have said that the right of property in a slave is

distinctly and expressly affirmed in the Constitution, are

not prepared to show that no constitution or law can destroy

that right. I say I believe it

will take a far better argument than a mere sneer to show to

the minds of intelligent men that whoever has so said, is

not prepared, whenever public sentiment is so far advanced

as to justify it. to say the

other. This is but an opinion,

and the opinion of one very humble man; but it is my opinion

that the Dred Scott decision, as it is, never would have

been made in its present form if the party that made it had

not been sustained previously by the elections.

My own opinion is, that the new Dred Scott

decision, deciding against the right of the people of the

States to exclude slavery, will never he made, if that party

is not sustained by the elections. I

believe, further, that it is just as sure to be made as

tomorrow is to come, if that party shall be sustained. I have said, upon a former

occasion, and I repeat it now, that the course of argument

that Judge Douglas makes

use of upon this subject (I charge not his motives in this),

is preparing the public mind for that new Dred Scott

decision. I have asked him

again to point out to me the reasons for his first adherence

to the Dred Scott decision as it is. I

have turned his attention to the fact that General Jackson

differed with him in regard to the political obligation of a

Supreme Court decision. I have

asked his attention to the fact that Jefferson

differed with him in regard to the political obligation of a

Supreme Court decision. Jefferson said, that “Judges are as

honest as other men. and not

more so.” And he said, substantially, that “whenever a free

people should give up in absolute submission to any

department of government, retaining for themselves no appeal

from it, their liberties were gone.” I

have asked his attention to the fact that the Cincinnati platform,

upon which he says he stands, disregards a time-honored

decision of the Supreme Court, in denying the power of

Congress to establish a National Bank.

I have asked his attention to the fact that he

himself was one of the most active instruments at one time

in breaking down the Supreme Court of the State of Illinois,

because it had made a decision distasteful to him—a struggle

ending in the remarkable circumstance of his sitting down as

one of the new Judges who were to overslaugh that

decision—getting his title of Judge in that very way.

So

far in this controversy I can get no answer at all from

Judge Douglas upon these subjects. Not

one can I get from him, except that he swells himself up and

says, “All of us who stand by the decision of the Supreme

Court are the friends of the Constitution; all you fellows

that dare question it in any way, are the enemies of the

Constitution.” Now, in this very devoted adherence to this

decision, in opposition to all the great political leaders

whom he has recognized as leaders—in opposition to his

former self and history, there is something very marked. And the manner in which he adheres

to it—not as being right upon the merits, as he conceives

(because he did not discuss that at all), but as being

absolutely obligatory upon every one simply because of the

source from whence it comes—as that which no man can

gainsay, whatever it may be—this is another marked feature

of his adherence to that decision. It

marks it in this respect, that it commits him to the next

decision, whenever it comes, as being as obligatory as this

one, since he does not investigate it, and won’t inquire

whether this opinion is right or wrong.

So he takes the next one without inquiring whether it is right or wrong. He

teaches men this doctrine, and in so doing prepares the

public mind to take the next decision when it comes, without

any inquiry. In this I think I

argue fairly (without questioning motives at all), that

Judge Douglas is most ingeniously and powerfully preparing

the public mind to take that decision when it comes; and not

only so, but he is doing it in various other ways.

In these general maxims about liberty—in his

assertions that he “don’t care whether slavery is voted up

or voted down;” that “whoever wants slavery has a right to

have it;” that “upon principles of equality it should be

allowed to go every where;” that “there is no inconsistency

between free and slave institutions.” In this he is also

preparing (whether purposely or not) the way for making the

institution of slavery national! I

repeat again, for I wish no misunderstanding, that I do not

charge that he means it so; but I call upon your minds to

inquire, if you were going to get the best instrument you

could, and then set it to work in the most ingenious way, to

prepare the public mind for this movement, operating in the

free States, where there is now an abhorrence of the

institution of slavery, could you find an instrument so

capable of doing it as Judge Douglas? or

one employed in so apt a way to do it?

I

have said once before, and I will repeat it now, that Mr.

Clay, when he was once answering an objection to the

Colonization Society, that it had a tendency to the ultimate

emancipation of the slaves, said that “those who would

repress all tendencies to liberty and ultimate emancipation

must do more than put down the benevolent efforts of the

Colonization Society—they must go back to the era of our

liberty and independence, and muzzle the cannon that

thunders its annual joyous return—they must blot out the

moral lights around us—they must penetrate the human soul,

and eradicate the light of reason and the love of liberty!”

And I do think—I repeat, though

I said it on a former occasion—that Judge Douglas, and

whoever like him teaches that the negro has no share, humble

though it may be, in the Declaration of Independence, is

going back to the era of our liberty and independence, and,

so far as in him lies, muzzling the cannon that thunders its

annual joyous return; that he is blowing out the moral

lights around us, when he contends that whoever wants slaves

has a right to hold them; that he is penetrating, so far as

lies in his power, the human soul, and eradicating the light

of reason and the love of liberty, when he is in every

possible way preparing the public mind, by his vast

influence, for making the institution of slavery perpetual

and national.

There

is, my friends, only one other point to which I will call

your attention for the remaining time that I have left me,

and perhaps I shall not occupy the entire time that I have,

as that one point may not take me clear through it.

Among

the interrogatories that Judge Douglas propounded to me at Freeport, there was one in about this

language: “Are you opposed to the acquisition of any further

territory to the United

States, unless slavery

shall first be prohibited therein?” I

answered as I thought, in this way, that I am not generally

opposed to the acquisition of additional territory, and that

I would support a proposition for the acquisition of

additional territory, according as my supporting it was or

was not calculated to aggravate this slavery question

amongst us. I then proposed to

Judge Douglas another interrogatory, which was correlative

to that: “Are you in favor of acquiring additional territory

in disregard of how it may affect us upon the slavery

question?” Judge Douglas

answered, that is, in his own way he answered it.

I believe that, although he took a good many words