SECOND JOINT DEBATE,

AT

August

27, 1858.

|

The

second

debate is perhaps most widely known for the "Freeport

Doctrine," the idea that a Territory could effectively deny

slavery, not by an explicit law to that effect (this would

violate the recent Dred Scott decision), but by refusing to

pass the necessary "police regulations" which would be

necessary for the institution to survive. The doctrine

was espoused by Douglas in response to a question from

Lincoln; posing |

|

| the

question was a very clever gambit by Lincoln, because while

Douglas's answer may have swayed enough "free-soil" voters to

keep him in the Senate, it killed any chance he had of any

Southern support for the Democratic Presidential nomination in

1860. Stephen Douglas also premiered a story he would

tell several times during the debates, about seeing the noted

black Abolitionist Frederick Douglass, drive up (at a previous

speaking engagement of Senator Douglas) in a carriage with a

white woman, being driven by her husband or father (the

details changed from instance to instance). |

||

|

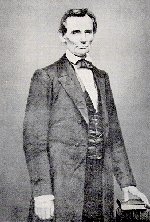

MR. LINCOLN'S SPEECH.

LADIES AND

GENTLEMEN: On Saturday

last, Judge Douglas and myself first met in public

discussion. He spoke one hour,

I an hour and a half, and he replied for half an hour. The order is now reversed. I

am to speak an hour, he an hour and a half, and then I am to

reply for half an hour. I

propose to devote myself during the first hour to the scope

of what was brought within the range of his half hour speech

at I

have supposed myself, since the organization of the

Republican party at Having

said thus much, I will take up the Judge's interrogatories

as I find them printed in the Question

1. “I desire to know whether Answer. I do not now, nor ever did, stand in favor of the unconditional repeal of the Fugitive Slave law. Q.

2. “I desire him to answer whether he stands pledged to-day,

as he did in 1854, against the admission of any more slave

States into the A.

I do not now, or ever did, stand pledged against the

admission of any more slave States into the Q.

3. “I want to know whether he stands pledged against the

admission of a new State into the A.

I do not stand pledged against the admission of a new State

into the Q.

4. “I want to know whether he stands to-day pledged to the

abolition of slavery in the A.

I do not stand to-day pledged to the abolition of slavery in

the Q. 5. “I desire him to answer whether he stands pledged to the prohibition of the slave-trade between the different States?” A. I do not stand pledged to the prohibition of the slave-trade between the different States. Q.

6. “I desire to know whether he stands pledged to prohibit

slavery in all the Territories of the A.

I am impliedly, if not expressly, pledged to a belief in the

right and duty of Congress

to prohibit slavery in all the Q. 7. “I desire him to answer whether he is opposed to the acquisition of any new territory unless slavery is first prohibited therein?” A. I am not generally opposed to honest acquisition of territory; and, in any given case, I would or would not oppose such acquisition, accordingly as I might think such acquisition would or would not aggravate the slavery question among ourselves. Now, my friends, it will be perceived upon an examination of these questions and answers, that so far I have only answered that I was not pledged to this, that or the other. The Judge has not framed his interrogatories to ask me anything more than this, and I have answered in strict accordance with the interrogatories, and have answered truly that I am not pledged at all upon any of the points to which I have answered. But I am not disposed to hang upon the exact form of his interrogatory. I am rather disposed to take up at least some of these questions, and state what I really think upon them. As

to the first one, in regard to the Fugitive Slave law, I

have never hesitated to say, and I do not now hesitate to

say, that I think, under the Constitution of the In

regard to the other question, of whether I am pledged to the

admission of anymore slave States into the The third interrogatory is answered by the answer to the second, it being, as I conceive, the same as the second. The

fourth one is in regard to the abolition of slavery in the In regard to the fifth interrogatory, I must say here, that as to the question of the abolition of the slave-trade between the different States, I can truly answer, as I have, that I am pledged to nothing about it. It is a subject to which I have not given that mature consideration that would make me feel authorized to state a position so as to hold myself entirely bound by it. In other words, that question has never been prominently enough before me to induce me to investigate whether we really have the constitutional power to do it. I could investigate it if I had sufficient time, to bring myself to a conclusion upon that subject; but I have not done so, and I say so frankly to you here, and to Judge Douglas. I must say, however, that if I should be of opinion that Congress does possess the constitutional power to abolish the slave-trade among the different States, I should still not be in favor of the exercise of that power unless upon some conservative principle as I conceive it, akin to what I have said in relation to the abolition of slavery in the District of Columbia. My

answer as to whether I desire that slavery should be

prohibited in all the Territories of the Now

in all this, the Judge has me, and he has me on the record.

I suppose he had flattered

himself that I was really entertaining one set of opinions

for one place and another set for another place—that I was

afraid to say at one place what I uttered at another. What I

am saying here I suppose I say to a vast audience as

strongly tending to Abolitionism as any audience in the

State of I now proceed to propound to the Judge the interrogatories, so far as I have framed them. I will bring forward a new installment when I get them ready. I will bring them forward now, only reaching to number four. The first one is: Question 1. If the people of Kansas shall, by means entirely unobjectionable in all other respects, adopt a State Constitution, and ask admission into the Union under it, before they have the requisite number of inhabitants according to the English bill —some ninety-three thousand—will you vote to admit them? Q.

2. Can the people of a Q.

3. If the Supreme Court of the

Q.

4. Are you in favor of

acquiring additional territory, in disregard of how such

acquisition may affect the nation on the slavery question? As

introductory to these interrogatories which Judge Douglas

propounded to me at I allude to this extraordinary matter in this canvass for some further purpose than anything yet advanced. Judge Douglas did not make his statement upon that occasion as matters that he believed to be true, but he stated them roundly as being true, in such form as to pledge his veracity for their truth. When the whole matter turns out as it does, and when we consider who Judge Douglas is—that he is a distinguished Senator of the United States—that he has served nearly twelve years as such—that his character is not at all limited as an ordinary Senator of the United States, but that his name has become of world-wide renown—it is most extraordinary that he should so far forget all the suggestions of justice to an adversary, or of prudence to himself, as to venture upon the assertion of that which the slightest investigation would have shown him to be wholly false. I can only account for his having done so upon the supposition that that evil genius which has attended him through his life, giving to him an apparent astonishing prosperity, such as to lead very many good men to doubt there being any advantage in virtue over vice—I say I can only account for it on the supposition that that evil genius has at last made up its mind to forsake him. And I may add that another extraordinary feature of the Judge's conduct in this canvass—made more extraordinary by this incident—is, that he is in the habit, in almost all the speeches he makes, of charging falsehood upon his adversaries, myself and others. I now ask whether he is able to find in any thing that Judge Trumbull, for instance, has said, or in any thing that I have said, a justification at all compared with what we have, in this instance, for that sort of vulgarity. I

have been in the habit of charging as a matter of belief on

my part, that, in the introduction of the The Judge insists that, in the first speech I made, in which I very distinctly made that charge, he thought for a good while I was in fun!—that I was playful—that I was not sincere about it—and that he only grew angry and somewhat excited when he found that I insisted upon it as a matter of earnestness. He says he characterized it as a falsehood as far as I implicated his moral character in that transaction. Well, I did not know, till he presented that view, that I had implicated his moral character, he is very much in the habit, when he argues me up into a position I never thought of occupying, of very cosily saying he has no doubt Lincoln is “conscientious” in saying so. He should remember that I did not know but what he was ALTOGETHER “CONSCIENTIOUS” in that matter. I can conceive it possible for men to conspire to do a good thing, and I really find nothing in Judge Douglas's course or arguments that is contrary to or inconsistent with his belief of a conspiracy to nationalize and spread slavery as being a good and blessed thing, and so I hope he will understand that I do not at all question but that in all this matter he is entirely “conscientious.” But

to draw your attention to one of the points I made in this

case, beginning at the beginning. When

the Nebraska bill was introduced, or a short time afterward,

by an amendment, I believe, it was provided that it must be

considered “the true intent and meaning of this act not to

legislate slavery into any State or Territory, or to exclude

it there from, but to leave the people thereof perfectly

free to form and regulate their own domestic institutions in

their own way, subject only to the Constitution of the

United States.” I have called

his attention to the fact that when he and some others began

arguing that they were giving an increased degree of liberty

to the people in the Territories over and above what they

formerly had on the question of slavery, a question was

raised whether the law was enacted to give such

unconditional liberty to the people, and to test the

sincerity of this mode of argument, Mr. Chase, of Ohio,

introduced an amendment, in which he made the law—if the

amendment were adopted—expressly declare that the people of

the Territory should have the power to exclude slavery if

they saw fit. I have asked attention also to the fact

that Judge Douglas and those who acted with him, voted that

amendment down, notwithstanding it expressed exactly the

thing they said was the true intent and meaning of the law.

I have called attention to the

fact that in subsequent times, a decision of the Supreme

Court has been made, in which it has been declared that a

Territorial Legislature has no constitutional right to

exclude slavery. And I have

argued and said that for men who did intend that the people

of the Territory should have the right to exclude slavery

absolutely and unconditionally, the voting down of Chase's

amendment is wholly inexplicable. It

is a puzzle—a riddle. But I

have said that with men who did look forward to such a

decision, or who had it in contemplation, that such a

decision of the Supreme Court would or might be made, the

voting down of that amendment would be perfectly rational

and intelligible. It would keep

Congress from coming in collision with the decision when it

was made. Any body can conceive

that if there was an intention or expectation that such a

decision was to follow, it would not be a very desirable

party attitude to get into for the Supreme Court—all or

nearly all its members belonging to the same party—to decide

one way, when the party in Congress had decided the other

way. Hence it would be very

rational for men expecting such a decision, to keep the

niche in that law clear for it. After

pointing this out, I tell Judge Douglas that it looks to me

as though here was the reason why Chase's amendment was

voted down. I tell him that as

he did it, and knows why he did it, if it was done for a

reason different from this, he knows what that

reason was, and can tell us what it was. I

tell him, also, it will be vastly more satisfactory to the

country for him to give some other plausible, intelligible

reason why it was voted down than to stand

upon his dignity and call people liars. Well, on Saturday he

did make his answer, and what do you think it was? He

says

if I had only taken upon myself to tell the whole truth

about that amendment of Chase's, no explanation would have

been necessary on his part—or words to that effect. Now,

I say here, that I am quite unconscious of having suppressed

any thing material to the case, and I am very frank to admit

if there is any sound reason other than that which appeared

to me material, it is quite fair for him to present it. What reason does he propose? That when Chase came forward with

his amendment expressly authorizing the people to exclude

slavery from the limits of every Territory, Gen. Cass

proposed to Chase, if he (Chase) would add to his amendment

that the people should have the power to introduce or

exclude, they would let it go. This

is substantially all of his reply. And

because Chase would not do that, they voted his amendment

down. Well, it turns out, I

believe, upon examination, that General Cass took some part

in the little running debate upon that amendment, and then

ran away and did not vote on it at all. Is not that the fact? So

confident, as I think, was General Cass that there was a

snake somewhere about, he chose to run away from the whole

thing. This is an inference I

draw from the fact that, though he took part in the debate,

his name does not appear in the ayes and noes. But

does Judge Douglas's reply amount to a satisfactory answer? [Cries of “yes,” “yes,” and “no,”

“no.”] There is some little

difference of opinion here. But I ask attention to a few

more views bearing on the question of whether it amounts to

a satisfactory answer. The men

who were determined that that amendment should not get into

the bill and spoil the place where the Dred Scott decision

was to come in, sought an excuse to get rid of it somewhere. One of these ways—one of these

excuses—was to ask Chase to add to his proposed amendment a

provision that the people might introduce

slavery if they wanted to. They

very well knew Chase would do no such thing—that Mr. Chase

was one of the men differing from them on the broad

principle of his insisting that freedom was better

than slavery—a man who would not consent to enact a law,

penned with his own hand, by which he was made to recognize

slavery on the one hand and liberty on the other as precisely

equal; and when they insisted on his doing this, they

very well knew they insisted on that which he would not for

a moment think of doing, and that they were only bluffing

him. I believe (I have not,

since he made his answer, had a chance to examine the

journals or Congressional Globe, and

therefore speak from memory)—I believe the state of the bill

at that time, according to parliamentary rules, was such

that no member could propose an additional amendment to

Chase's amendment. I rather

think this is the truth—the Judge shakes his head.

Very well. I would like to know, then, if

they wanted Chase's amendment fixed over, why somebody

else could not have offered to do it?

If they wanted it amended, why did they not offer

the amendment? Why did they

stand there taunting and quibbling at Chase? Why

did they not put it in themselves? But,

to

put it on the other ground; suppose that there was such an

amendment offered, and Chase's was an amendment to an

amendment; until one is disposed of by parliamentary law,

you cannot pile another on. Then

all these gentlemen had to do was to vote Chase's on, and

then in the amended form in which the whole stood, add their

own amendment to it if they wanted to put it in that shape.

This was all they were obliged

to do, and the ayes and noes show that there were thirty-six

who voted it down, against ten who voted in favor of it. The thirty-six held entire sway and

control. They could in some

form or other have put that bill in the exact shape they

wanted. If there was a rule preventing their amending it at

the time, they could pass that, and then Chase's amendment

being merged, put it in the shape they wanted. They

did not choose to do so, but they went into a quibble with

Chase to get him to add what they knew he would not add, and

because he would not, they stand upon that flimsy pretext

for voting down what they argued was the meaning and intent

of their own bill. They left

room thereby for this Dred Scott decision, which goes very

far to make slavery national throughout the I

pass one or two points I have because my time will very soon

expire, but I must be allowed to say that Judge Douglas

recurs again, as he did upon one or two other occasions, to

the enormity of Lincoln—an insignificant individual like

Lincoln—upon his ipse dixit charging a

conspiracy upon a large number of members of Congress, the

Supreme Court and two Presidents, to nationalize slavery. I want to say that, in the first

place, I have made no charge of this sort upon my ipse

dixit. I have only arrayed the evidence tending to

prove it, and presented it to the understanding of others,

saying what I think it proves, but giving you the means of

judging whether it proves it or not. This

is precisely what I have done. I

have not placed it upon my ipse dixit at

all. On this occasion, I wish

to recall his attention to a piece of evidence which I

brought forward at Ottawa on Saturday, showing that he had

made substantially the same charge against

substantially the same persons, excluding

his dear self from the category. I

ask him to give some attention to the evidence which I

brought forward, that he himself had discovered a “fatal

blow being struck” against the right of the people to

exclude slavery from their limits, which fatal blow he

assumed as in evidence in an article in the Washington Union,

published “by authority.” I ask

by whose authority? He

discovers a similar or identical provision in the Lecompton

Constitution. Made by whom? The framers of that Constitution. Advocated by whom? By

all the members of the party in the nation, who advocated

the introduction of I have asked his attention to the evidence that he arrayed to prove that such a fatal blow was being struck, and to the facts which he brought forward in support of that charge—being identical with the one which he thinks so villainous in me. He pointed it not at a newspaper editor merely, but at the President and his Cabinet and the members of Congress advocating the Lecompton Constitution and those framing that instrument. I must again be permitted to remind him, that although my ipse dixit may not be as great as his, yet it somewhat reduces the force of his calling my attention to the enormity of my making a like charge against him. Go on, Judge Douglas.

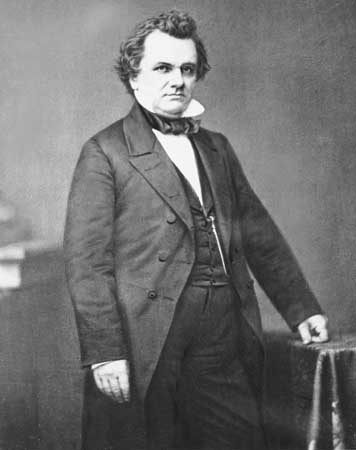

MR.

LADIES AND

GENTLEMEN: The silence

with which you have listened to Mr. Lincoln during his hour

is creditable to this vast audience, composed of men of

various political parties. Nothing

is more honorable to any large mass of people assembled for

the purpose of a fair discussion, than that kind and

respectful attention that is yielded not only to your

political friends, but to those who are opposed to you in

politics. I am glad that at

last I have brought Mr. Lincoln to the conclusion that he

had better define his position on certain political

questions to which I called his attention at First,

he desires to know if the people of The

next question propounded to me by Mr. Lincoln is, can the

people of a Territory in any lawful way, against the wishes

of any citizen of the In

this connection, I will notice the charge which he has

introduced in relation to Mr. Chase's amendment. I

thought that I had chased that amendment out of Mr.

Lincoln's brain at His

amendment was to this effect. It

provided that the Legislature should have the power to

exclude slavery; and General Cass suggested, “why not give

the power to introduce as well as exclude?” The

answer was, they have the power already in the bill to do

both. Chase was afraid his

amendment would be adopted if he put the alternative

proposition and so make it fair both ways, but would not

yield. He offered it for the

purpose of having it rejected. He

offered it, as he has himself avowed over and over again,

simply to make capital out of it for the stump. He expected

that it would be capital for small politicians in the

country, and that they would make an effort to deceive the

people with it, and he was not mistaken, for The

third question which Mr. Lincoln presented is, if the

Supreme Court of the The

fourth question of Mr. Lincoln is, are you in favor of

acquiring additional territory, in disregard as to how such

acquisition may affect the The

Black Republican creed lays it down expressly, that under no

circumstances shall we acquire any more territory unless

slavery is first prohibited in the country.

I ask Mr. Lincoln whether he is in favor of that

proposition. Are you

[addressing Mr. I

trust now that Mr. Lincoln will deem himself answered on his

four points. He racked his

brain so much in devising these four questions that he

exhausted himself and had not strength enough to invent the

others. As soon as he is able

to hold a council with his advisers, Lovejoy, Farnsworth,

and Fred Douglass, he will frame and propound others.

[“Good, good.”] You

Black Republicans who say good, I have no doubt think that

they are all good men. I have

reason to recollect that some people in this country think

that Fred Douglass is a very good man. The

last time I came here to make a speech, while talking from

the stand to you, people of Freeport, as I am doing to-day,

I saw a carriage, and a magnificent one it was, drive up and

take a position on the outside of the crowd; a beautiful

young lady was sitting on the box-seat, whilst Fred Douglass

and her mother reclined inside, and the owner of the

carriage acted as driver. 1 saw this in your own town. [“What of it?”]

All I have to say of it is this, that if you, Black

Republicans, think that the negro ought to be on a social

equality with your wives and daughters, and ride in a

carriage with your wife, whilst you drive the team, you have

perfect right to do so. I am

told that one of Fred Douglass's kinsmen, another rich black

negro, is now traveling in this part of the State making

speeches for his friend Lincoln as the champion of black

men. [“What have you to say against it?”] All I have to say

on that subject is, that those of you who believe that the

negro is your equal and ought to be on an equality with you

socially, politically, and legally, have a right to

entertain those opinions, and of course will vote for Mr.

Lincoln. I

have a word to say on Mr. Lincoln's answer to the

interrogatories contained in my speech at Ottawa, and which

he has pretended to reply to here to-day. Mr.

Lincoln makes a great parade of the fact that I quoted a

platform as having been adopted by the Black Republican

party at When

I put the direct questions to Mr. Lincoln to ascertain

whether he now stands pledged to that creed—to the

unconditional repeal of the Fugitive Slave law, a refusal to

admit any more slave States into the Union even if the

people want them, a determination to apply the Wilmot

Proviso, not only to all the territory we now have, but all

that we may hereafter acquire, he refused to answer, and his

followers say, in excuse, that the resolutions upon which I

based my interrogatories were not adopted at the “right

spot.” Lincoln and his

political friends are great on “spots.” In Congress, as a representative of

this State, he declared the Mexican war to be unjust and

infamous, and would not support it, or acknowledge his own

country to be right in the contest, because he said that

American blood was not shed on American soil in the “right

spot.” And now he cannot answer the questions I put to

him at “During

the late discussions in this city, Then

follows the identical platform, word for word, which I read

at When

I quoted the resolutions at Now, I will show you that if I have made a mistake as to the place where these resolutions were adopted—and when I get down to Springfield I will investigate the matter and see whether or not I have—that the principles they enunciate were adopted as the Black Republican platform [“white, white”], in the various counties and Congressional Districts throughout the north end of the State in 1854. This platform was adopted in nearly every county that gave a Black Republican majority for the Legislature in that year, and here is a man [pointing to Mr. Denio, who sat on the stand near Deacon Bross] who knows as well as any living man that it was the creed of the Black Republican party at that time. I would be willing to call Denio as a witness, or any other honest man belonging to that party. I will now read the resolutions adopted at the Rockford Convention on the 30th of August, 1854, which nominated Washburne for Congress. You elected him on the following platform: Resolved, That the continued and increasing aggressions of slavery in our country are destructive of the best rights of a free people, and that such aggressions cannot be successfully resisted without the united political action of all good men. Resolved, That the citizens of the Resolved, That we accept this issue forced upon us by the slave power, and, in defense of freedom, will co-operate and be known as Republicans, pledged to the accomplishment of the following purposes: To bring the Administration of the Government back to the control of 'first principles; to restore Kansas and Nebraska to the position of free Territories; to repeal and entirely abrogate the Fugitive Slave law; to restrict slavery to those States in which it exists; to prohibit the admission of any more slave States into the Union; to exclude slavery from all the Territories over which the General Government has exclusive jurisdiction, and to resist the acquisition of any more Territories unless the introduction of slavery therein forever shall have been prohibited. Resolved, That in furtherance of these principles we will use such constitutional and lawful means as shall seem best adapted to their accomplishment, and that we will support no man for office under the General or State Government who is not positively committed to the support of these principles, and whose personal character and conduct is not a guaranty that he is reliable and shall abjure all party allegiance and ties. Resolved, That we cordially invite persons of all former political parties whatever in favor of the object expressed in the above resolutions to unite with us in carrying them into effect. Well,

you think that is a very good platform, do you not? If

you do, if you approve it now, and think it is all right,

you will not join with those men who say that I libel you by

calling these your principles, will you? Now,

Mr. Lincoln complains; Mr. Lincoln charges that I did you

and him injustice by saying that this was the platform of

your party. I am told that

Washburne made a speech in But I am glad to find that you are more honest in your abolitionism than your leaders, by avowing that it is your platform, and right in your opinion. In

the adoption of that platform, you not only declared that

you would resist the admission of any more slave States, and

work for the repeal of the Fugitive Slave law, but you

pledged yourselves not to vote for any man for State or

Federal offices who was not committed to these principles. You were thus committed. Similar

resolutions to those were adopted in your county Convention

here, and now with your admissions that they are your

platform and embody your sentiments now as they did then,

what do you think of Mr. Lincoln, your candidate for the U.

S. Senate, who is attempting to dodge the responsibility of

this platform, because it was not adopted in the right spot.

I thought that it was adopted in

A voice—“Couldn't you modify and call it brown ?” Mr. Douglas—Not a bit. I thought that you were becoming a little brown when your members in Congress voted for the Crittenden-Montgomery bill, but since you have backed out from that position and gone back to Abolitionism, you are black and not brown. Gentlemen,

I have shown you what your platform was in 1854. You

still adhere to it. The same

platform was adopted by nearly all the counties where the

Black Republican party had a majority in 1854. I

wish now to call your attention to the action of your

representatives in the Legislature when they assembled

together at [Mr. Turner, who was one of the moderators, here interposed and said that he had drawn the resolutions which Senator Douglas had read.] Mr.

Douglas.—Yes,

and Turner says that he drew these resolutions.

[“Hurra for Turner,” “Hurra for Mr. Turner—“They are our creed exactly.” Mr.

Douglas—And yet When

the bargain between Lincoln and Trumbull was completed for

Abolitionizing the Whig and Democratic parties, they

“spread” over the State, Lincoln still pretending to be an

old line Whig, in order to “rope in” the Whigs, and Trumbull

pretending to be as good a Democrat as he ever was, in order

to coax the Democrats over into the Abolition ranks.

They played the part that “decoy ducks” play down

on the Mr. Turner—“I hope I was then and am now.” Mr.

Douglas—He swears that he hopes he was then and is now. He wrote that Black Republican

platform, and is satisfied with it now. I

admire and acknowledge Turner’s honesty. Every man of you

know that what he says about these resolutions being the

platform of the Black Republican party is true, and you also

know that each one of these men who are shuffling and trying

to deny it are only trying to cheat the people out of their

votes for the purpose of deceiving them still more after the

election. I propose to trace

this thing a little further, in order that you can see what

additional evidence there is to fasten this revolutionary

platform upon the Black Republican party. When

the Legislature assembled, there was an United States

Senator to elect in the place of Gen. Shields, and before

they proceeded to ballot, Lovejoy insisted on laying down

certain principles by which to govern the party. It

has been published to the world and satisfactorily proven

that there was, at the time the alliance was made between

Trumbull and Lincoln to Abolitionize the two parties, an

agreement that Lincoln should take Shields's place in the

United States Senate, and Trumbull should have mine so soon

as they could conveniently get rid of me. When

Lincoln was beaten for Shields's place, in a manner I will

refer to in a few minutes, he felt very sore and restive;

his friends grumbled, and some of them came out and charged

that the most infamous treachery had been practiced against

him; that the bargain was that Lincoln was to have had

Shields's place, and Trumbull was to have waited for mine,

but that Trumbull having the control of a few Abolitionized

Democrats, he prevented them from voting for Lincoln, thus

keeping him within a few votes of an election until he

succeeded in forcing the party to drop him and elect

Trumbull. Well, Now,

there are a great many Black Republicans of you who do not

know this thing was done. [“White,

white,” and great clamor.] I

wish to remind you that while Mr Lincoln was speaking there

was not a Democrat vulgar and blackguard enough to interrupt

him. But I know that the shoe

is pinching you. I am clinching

WHEREAS. Human slavery is a

violation of the principles of natural and revealed rights;

and whereas, the fathers of the Revolution, fully imbued

with the spirit of these principles, declared freedom to be

the inalienable birthright of all men; and whereas, the

preamble to the Constitution of the United States avers that

that instrument was ordained to establish justice, and

secure the blessings of liberty to ourselves and our

posterity; and whereas, in furtherance of the above

principles, slavery was forever prohibited in the old

North-west Territory, and more recently in all that

Territory lying west and north of the State of Missouri, by

the act of the Federal Government; and whereas, the repeal

of the prohibition last referred to, was contrary to the

wishes of the people of Illinois, a violation of an implied

compact, long deemed sacred by the citizens of the United

States, and a wide departure from the uniform action of the

General Government in relation to the extension of slavery;

therefore, Resolved, by the House of Representatives, the Senate concurring therein, That our Senators in Congress be instructed, and our Representatives requested to introduce, if not otherwise introduced, and to vote for a bill to restore such prohibition to the aforesaid Territories, and also to extend a similar prohibition to all territory which now belongs to the United States, or which may hereafter come under their jurisdiction. Resolved, That our Senators in Congress be

instructed, and our Representatives requested, to vote

against the admission of any State into the Union, the

Constitution of which does not prohibit slavery, whether the

territory out of which such State may have been formed shall

have been acquired by conquest, treaty, purchase, or from

original territory of the United States. Resolved, That our Senators in Congress be instructed, and our Representatives requested, to introduce and vote for a bill to repeal an act entitled “an act respecting fugitives from justice and persons escaping from the service of their masters;” and, failing in that, for such a modification of it as shall secure the right of habeas corpus and trial by jury before the regularly-constituted authorities of the State, to all persons claimed as owing service or labor. Those

resolutions

were introduced by Mr. Lovejoy immediately preceding the

election of Senator. They

declared first, that the Wilmot Proviso must be applied to

all territory north of 36 deg. 30 min. Secondly,

that it must be applied to all territory south of 36 deg. 30

min. Thirdly, that it must be

applied to all the territory now owned by the On

the next resolution the vote stood—yeas 33, nays 40, and on

the third resolution —yeas 35, nays 47. I

wish to impress it upon you, that every man who voted for

those resolutions, with but two exceptions, voted on the

next day for I

could go through the whole list of names here and show you

that all the Black Republicans in the Legislature, who voted

for Mr. Lincoln, had voted on the day previous for these

resolutions. For instance, here

are the names of Sargent and Little of Jo Daviess and

Carroll, Thomas J. Turner of Stephenson, Lawrence of Boone

and McHenry, Swan of Lake, Pinckney of Ogle county, and

Lyman of Winnebago. Thus you

see every member from your Congressional District voted for

Mr. Lincoln, and they were pledged not to vote for him

unless he was committed to the doctrine of no more slave

States, the prohibition of slavery in the Territories, and

the repeal of the Fugitive Slave law. Mr.

Lincoln tells you to-day that he is not pledged to any such

doctrine. Either Mr. Lincoln

was then committed to those propositions, or Mr. Turner

violated his pledges to you when he voted for him.

Either In regard to there being no more slave States, he is not pledged to that. He would not like, he says, to be put in a position where he would have to vote one way or another upon that question. I pray you, do not put him in a position that would embarrass him so much. Gentlemen, if he goes to the Senate, he may be put in that position, and then which way will he vote? [A Voice—“How will you vote?”] Mr.

Douglas—I will vote for the admission of just such a State

as by the form of their Constitution the people show they

want; if they want slavery, they shall have it; if they

prohibit slavery it shall be prohibited. They can form their

institutions to please themselves, subject only to the

Constitution; and I for one stand ready to receive them into

the I do not want to cheat any man out of his vote. No man is deceived in regard to my principles if I have the power to express myself in terms explicit enough to convey my ideas. Mr. Lincoln made a speech when he was nominated for the United States Senate which covers all these Abolition platforms. He there lays down a proposition so broad in its abolitionism as to cover the whole ground. “In my opinion it [the slavery agitation] will not cease until a crisis shall have been reached and passed. ‘A house divided against itself cannot stand.’ I believe this Government cannot endure permanently half slave and half free. I do not expect the house to fall—but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing or all the other. Either the opponents of Slavery will arrest the further spread of it, and place it where the public mind shall rest in the belief that it is in the course of ultimate extinction, or its advocates will push it forward till it shall become alike lawful in all the States—old as well as new, North as well as South.” There

you find that Mr. Lincoln lays down the doctrine that this He

tells you the Union cannot exist unless the States are all

free or all slave; he tells you that he is opposed to making

them all slave, and hence he is for making them all free, in

order that the Union may exist; and yet he will not say that

he will not vote against another slave State, knowing that

the Union must be dissolved if he votes for it. I

ask you if that is fair dealing? The

true intent and inevitable conclusion to be drawn from his

first Mr.

Lincoln says that he believes that this Mr.

Lincoln makes a charge of corruption against the Supreme

Court of the Mr.

Mr.

MR. LINCOLN'S REPLY. MY FRIENDS:

It will readily occur to you that I cannot, in half an hour,

notice all the things that so able a man as Judge Douglas

can say in an hour and a half; and I hope, therefore, if

there be any thing that he has said upon which you would

like to hear something from me, but which I omit to comment

upon, you will bear in mind that it would be expecting an

impossibility for me to go over his whole ground.

I can but take up some of the points that he has

dwelt upon, and employ my half-hour specially on them. The first thing I have to say to you is a word in regard to Judge Douglas's declaration about the “vulgarity and blackguardism” in the audience—that no such thing, as he says, was shown by any Democrat while I was speaking. Now, I only wish, by way of reply on this subject, to say that while I was speaking, I used no “vulgarity or blackguardism” toward any Democrat. Now,

my friends, I come to all this long portion of the Judge's

speech—perhaps half of it—which he has devoted to the

various resolutions and platforms that have been adopted in

the different counties in the different Congressional

Districts, and in the Illinois Legislature—which he supposes

are at variance with the positions I have assumed before you

to-day. It is true that many of

these resolutions are at variance with the positions I have

here assumed. All I have to ask

is that we talk reasonably and rationally about it. I

happen to know, the Judge's opinion to the contrary

notwithstanding, that I have never tried to conceal my

opinions, nor tried to deceive any one in reference to them.

He may go and examine all the

members who voted for me for United States Senator in 1855,

after the election of 1854. They

were pledged to certain things here at home, and were

determined to have pledges from me, and if he will find any

of these persons who will tell him any thing inconsistent

with what I say now, I will resign, or rather retire from

the race, and give him no more trouble. The

plain truth is this: At the introduction of the The

Judge has again addressed himself to the abolition

tendencies of a speech of mine, made at The

Judge complains that I did not fully answer his questions. If I have the sense to comprehend

and answer those questions, I have done so fairly. If

it

can be pointed out to me how I can more fully and fairly

answer him, I aver I have not the sense to see how it is to

be done. He says I do not

declare I would in any event vote for the admission of a

slave State into the He

says if I should vote for the admission of a slave State I

would be voting for a dissolution of the Union, because I

hold that the Judge

Douglas says he made a charge upon the editor of the Now,

gentlemen, you may take Judge Douglas's speech of March 22d,

1858, beginning about the middle of page 21, and reading to

the bottom of page 24, and you will find the evidence on

which I say that he did not make his charge against the

editor of the “Mr.

President, you here find several distinct propositions

advanced boldly by the “Remember

that this article was published in the Union

on the 17th of November, and on the 18th appeared the first

article giving the adhesion of the “

‘KANSAS AND

HER CONSTITUTION.—The

vexed question is settled. The problem is solved. The dead

point of danger is passed. All serious trouble to “And

a column, nearly, of the same sort. Then,

when you come to look into the Lecompton Constitution, you

find the same doctrine incorporated in it which was put

forth editorially in the “ ‘Article 7, Section 1. The right of property is before and higher than any constitutional sanction; and the right of the owner of a slave to such slave and its increase is the same and as invariable as the right of the owner of any property whatever.’ ” “Then in the schedule is a provision that the Constitution may be amended after 1864 by a two-thirds vote.” “ ‘But no alteration shall be made to affect the right of property in the ownership of slaves.’ “It

will be seen by these clauses in the Lecompton Constitution

that they are identical in spirit with this authoritative

article in the “When I saw that article in the Union of the 17th of November, followed by the glorification of the Lecompton Constitution on the 18th of November, and this clause in the Constitution asserting the doctrine that a State has no right to prohibit slavery within its limits, I saw that there was a fatal blow being struck at the sovereignty of the States of this Union.” Here

he says. “Mr. President, you here find several distinct

propositions advanced boldly, and apparently authoritatively.”

By whose authority, Judge

Douglas? Again, he says in

another place, “It will be seen by these clauses in the

Lecompton Constitution, that they are identical in spirit

with this authoritative article.” By whose authority? Who

do you mean to say authorized the publication of these

articles? He knows that the “When I saw that article in the Union of the 17th of November, followed by the glorification of the Lecompton Constitution on the 18th of November, and this clause in the Constitution asserting the doctrine that a State has no right to prohibit slavery within its limits, I saw that there was a fatal blow being struck at the sovereignty of the States of this Union.” I ask him if all this fuss was made over the editor of this newspaper. It would be a terribly “fatal blow” indeed which a single man could strike, when no President, no Cabinet officer, no member of Congress, was giving strength and efficiency to the moment. Out of respect to Judge Douglas's good sense I must believe he didn’t manufacture his idea of the “fatal” character of that blow out of such a miserable scapegrace as he represents that editor to be. But the Judge's eye is farther south now. Then, it was very peculiarly and decidedly north. His hope rested on the idea of visiting the great “Black Republican” party, and making it the tail of his new kite. He knows he was then expecting from day to day to turn Republican and place himself at the head of our organization. He has found that these despised “Black Republicans” estimate him by a standard which he has taught them none too well. Hence he is crawling back into his old camp, and you will find him eventually installed in full fellowship among those whom he was then battling, and with whom he now pretends to be at such fearful variance. [Loud applause and cries of “go on, go on.”] I cannot, gentlemen, my time has expired.

|