FOURTH JOINT DEBATE,

AT

September 18, 1858.

|

Charleston

was in a solidly Democratic district and not very friendly to

some of the more radical-seeming Republican proposals.

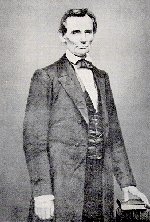

Thus, Lincoln began his presentation with a kind of disclaimer

that is often quoted as implying a degree of hypocrisy or

insincerity on his part. (Douglas certainly thought so,

as he would refer to this in later debates.) Historians

have wrestled with this passage for over 150 years, but I will

say naught about it. For his part, Douglas brought

up what would be a continuing theme, that Lincoln speaks one

way in northern Illinois, and another way in southern

Illinois. It does bear mentioning, that Lincoln's father

had died on his farm in Coles County (where Charleston is

located), and Lincoln's step-mother still lived there. In this debate, Lincoln made several references to a speech made by Lyman Trumbull and another one by Senator Douglas. Links to the appropriate extracts of those speeches are given in the appropriate places. |

|

|

MR. LINCOLN'S SPEECH.

LADIES AND GENTLEMEN: It will be very difficult for an audience so large as this to hear distinctly what a speaker says, and consequently it is important that as profound silence be preserved as possible. While I was at the hotel to-day, an elderly gentleman called upon me to know whether I was really in favor of producing a perfect equality between the negroes and white people. While I had not proposed to myself on this occasion to say much on that subject, yet as the question was asked me I thought I would occupy perhaps five minutes in saying something in regard to it. I will say then that I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races—that I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people; and I will say in addition to this that there is a physical difference between the white and black races which I believe will forever forbid the two races living together on terms of social and political equality. And inasmuch as they cannot so live, while they do remain together there must be the position of superior and inferior, and I as much as any other man am in favor of having the superior position assigned to the white race. I say upon this occasion I do not perceive that because the white man is to have the superior position the negro should be denied every thing. I do not understand that because I do not want a negro woman for a slave I must necessarily want her for a wife. My understanding is that I can just let her alone. I am now in my fiftieth year, and I certainly never have had a black woman for either a slave or a wife. So it seems to me quite possible for us to get along without making either slaves or wives of negroes. I will add to this that I have never seen, to my knowledge, a man, woman or child who was in favor of producing a perfect equality, social and political, between negroes and white men. I recollect of but one distinguished instance that I ever heard of so frequently as to be entirely satisfied of its correctness—and that is the case of Judge Douglas’s old friend Col. Richard M. Johnson. I will also add to the remarks I have made (for I am not going to enter at large upon this subject), that I have never had the least apprehension that I or my friends would marry negroes if there was no law to keep them from it; but as Judge Douglas and his friends seem to be in great apprehension that they might, if there were no law to keep them from it, I give him the most solemn pledge that I will to the very last stand by the law of this State, which forbids the marrying of white people with negroes. I will add one further word, which is this: that I do not understand that there is any place where an alteration of the social and political relations of the negro and the white man can be made except in the State Legislature—not in the Congress of the United States—and as I do not really apprehend the approach of any such thing myself, and as Judge Douglas seems to be in constant horror that some such danger is rapidly approaching, I propose as the best means to prevent it that the Judge be kept at home and placed in the State Legislature to fight the measure. I do not propose dwelling longer at this time on this subject. When

Judge Trumbull, our other Senator in Congress, returned to

Illinois in the month of August, he made a speech at

Chicago, in which he made what may be called a charge

against Judge Douglas, which I understand proved to be very

offensive to him. The Judge was

at that time out upon one of his speaking tours through the

country, and when the news of it reached him, as I am

informed, he denounced Judge Trumbull in rather harsh terms

for having said what he did in regard to that matter.

I was traveling at that time, and speaking at the

same places with Judge Douglas on subsequent days, and when

I heard of what Judge Trumbull had said of Douglas, and what

[*

See the extract of Douglas's speech at Jacksonville, here.] I

wish to say at the beginning that I will hand to the

reporters that portion of Judge Trumbull’s It will be perceived Judge Trumbull shows that Senator Bigler, upon the floor of the Senate, had declared there had been a conference among the Senators, in which conference it was determined to have an Enabling Act passed for the people of Kansas to form a Constitution under, and in this conference it was agreed among them that it was best not to have a provision for submitting the Constitution to a vote of the people after it should be formed. He then brings forward to show, and showing, as he deemed, that Judge Douglas reported the bill back to the Senate with that clause stricken out. He then shows that there was a new clause inserted into the bill, which would in its nature prevent a reference of the Constitution back for a vote of the people—if, indeed, upon a mere silence in the law, it could be assumed that they had the right to vote upon it. These are the general statements that he has made. [*

See I

propose to examine the points in Judge Douglas’s speech, in

which he attempts to answer that speech of Judge Trumbull’s. When you come to examine Judge

Douglas’s speech, you will find that the first point he

makes is: ‘‘Suppose it were true that there was such a

change in the bill, and that I struck it out—is that a proof

of a plot to force a Constitution upon them against their

will?” His striking out such a

provision, if there was such a one in the bill, he argues,

does not establish the proof that it was stricken out for

the purpose of robbing the people of that right.

I would say, in the first place, that that would be

a most manifest reason for it.

It is true, as Judge Douglas states, that many

Territorial bills have passed without having such a

provision in them. I believe it

is true, though I am not certain, that in some instances,

Constitutions framed under such bills have been submitted to

a vote of the people, with the law silent upon the subject,

but it does not appear that they once had their Enabling

Acts framed with an express provision for

submitting the Constitution to be framed to a vote of the

people, and then that they were stricken out when Congress

did not mean to alter the effect of the law.

That there have been bills which never had the

provision in, I do not question; but when was that provision

taken out of one that it was in? More

especially does this evidence tend to prove the proposition

that But

I must hurry on. The next

proposition that Judge Douglas puts is this: “But

upon examination it turns out that the Toombs bill never did

contain a clause requiring the Constitution to be

submitted.” This is a mere

question of fact, and can be determined by evidence.

I only want to ask this question—why did not Judge

Douglas say that these words were not stricken out of the

Toombs bill, or this bill from which it is alleged the

provision was stricken out—a bill which goes by the name of

Toombs, because he originally brought it forward? I

ask why, if the Judge wanted to make a direct issue with “That the following propositions be and the same are hereby offered to the said Convention of the people of Kansas when formed, for their free acceptance or rejection; which, if accepted by the Convention and ratified by the people at the election for the adoption of the Constitution, shall be obligatory upon the United States and the said State of Kansas.” Now,

Trumbull alleges that these last words were stricken out of

the bill when it came back, and he says this was a provision

for submitting the Constitution to a vote of the people, and

his argument is this: “Would it have been possible to ratify

the land propositions at the election for the adoption of

the Constitution, unless such an election was to be held?” That is Another

one of the points that Judge Douglas makes upon Trumbull,

and at very great length, is, that Trumbull, while the bill

was pending, said in a speech in the Senate that he supposed

the Constitution to be made would have to be submitted to

the people. He asks, if Another

one of the points Judge Douglas makes upon Judge Trumbull

is, that when he spoke in Chicago he made his charge to rest

upon the fact that the bill had the provision in it for

submitting the Constitution to a vote of the people, when it

went into his (Judge Douglas’s) hands, that it was missing

when he reported it to the Senate, and that in a public

speech he had subsequently said the alteration in the bill

was made while it was in committee, and that they were made

in consultation between him (Judge Douglas) and Toombs. And Judge Douglas goes on to

comment upon the fact of Trumbull’s adducing in his Alton

speech the proposition that the bill not only came back with

that proposition stricken out, but with another clause and

another provision in it, saying that “until the complete

execution of this act there shall be no election in said

Territory,”—which Trumbull argued was not only taking the

provision for submitting to a vote of the people out of the

bill, but was adding an affirmative one, in that it

prevented the people from exercising the right under a bill

that was merely silent on the question.

Now in regard to what he says, that Trumbull shifts

the issue—that he shifts his ground—and I believe he uses

the term, that “it being proven false, he has changed

ground”—I call upon all of you, when you come to examine

that portion of Trumbull’s speech (for it will make a part

of mine), to examine whether Trumbull has shifted his ground

or not. I say he did not shift

his ground, but that he brought forward his original charge

and the evidence to sustain it yet more fully, but precisely

as he originally made it. Then,

in addition thereto, he brought in a new piece of evidence. He shifted no ground.

He brought no new piece of evidence inconsistent

with his former testimony, but he brought a new piece,

tending, as he thought, and as I think, to prove his

proposition. To illustrate: A

man brings an accusation against another, and on trial the

man making the charge introduces A and B to prove the

accusation. At a second trial

he introduces the same witnesses, who tell the same story as

before, and a third witness, who tells the same thing and in

addition, gives further testimony corroborative of the

charge. So with But

Judge Douglas says that he himself moved to strike out that

last provision of the bill, and that on his motion it was

stricken out and a substitute inserted.

That I presume is the truth. I

presume it is true that that last proposition was stricken

out by Judge Douglas. In

the clause of Judge Douglas’s speech upon this subject he

uses this language toward Judge Trumbull.

He says: “He forges his evidence from beginning to

end, and by falsifying the record he endeavors to bolster up

his false charge.” Well, that

is a pretty serious statement. But

while I am dealing with this question, let us see what “I was present when that subject was discussed by Senators before the bill was introduced, and the question was raised and discussed, whether the Constitution, when formed, should be submitted to a vote of the people. It was held by those most intelligent on the subject, that in view of all the difficulties surrounding that Territory, the danger of any experiment at that time of a popular vote, it would be better there should be no such provision in the Toombs bill; and it was my understanding, in all the intercourse I had, that the Convention would make a Constitution, and send it here without submitting it to the popular vote.” Then

“

‘Nothing was further from my mind than to allude to any

social or confidential interview. The

meeting was not of that character. Indeed,

it was semi-official and called to promote the public good. My recollection was clear that I

left the conference under the impression that it had been

deemed best to adopt measures to admit “ ‘That the following propositions be, and the same are hereby offered to the said Convention of the people of Kansas, when formed, for their free acceptance or rejection; which, if accepted by the Convention and ratified by the people at the election for the adoption of the Constitution, shall be obligatory upon the United States and the said State of Kansas.’ “

‘The bill read in his place by the Senator from Now

these things “That

during the last session of Congress, I [Mr. Douglas]

reported a bill from the Committee on Territories, to

authorize the people of Now

A voice—“He will.” Mr.

“I

will ask the Senator to show me an intimation, from any one

member of the Senate, in the whole debate on the Toombs

bill, and in the Judge

Trumbull says “Judge Douglas, however, on the same day and in the same debate, probably recollecting or being reminded of the fact that I had objected to the Toombs bill when pending that it did not provide for a submission of the Constitution to the people, made another statement, which is to be found in the same volume of the Globe, page 22, in which he says:” “ ‘That the bill was silent on this subject was true, and my attention was called to that about the time it was passed; and I took the fair construction to be, that powers not delegated were reserved, and that of course the Constitution would be submitted to the people.’ “Whether this statement is consistent with the statement just before made, that had the point been made it would have been yielded to, or that it was a new discovery, you will determine.” So

I say. I do not know whether

Judge Douglas will dispute this, and yet maintain his

position that The

point upon Judge Douglas is this. The

bill that went into his hands had the provision in it for a

submission of the Constitution to the people; and I say its

language amounts to an express provision for a submission,

and that he took the provision out. He

says it was known that the bill was silent in this

particular; but I say, Judge Douglas, it was

not silent when you got it. It

was vocal with the declaration when you got it, for a

submission of the Constitution to the people.

And now, my direct question to Judge Douglas is, to

answer why, if he deemed the bill silent on this point, he

found it necessary to strike out those particular harmless

words. If he had found the bill

silent and without this provision, he might say what he does

now. If he supposes it was

implied that the Constitution would be submitted to a vote

of the people, how could these two lines so encumber the

statute as to make it necessary to strike them out?

How could he infer that a submission was still

implied, after its express provision had been stricken from

the bill? I find the bill vocal

with the provision, while he silenced it.

He took it out, and although he took out the other

provision preventing a submission to a vote of the people, I

ask, why did you first put it in? I

ask him whether he took the original provision out, which I was told, before my last paragraph, that my time was within three minutes of being out. I presume it is expired now. I therefore close.

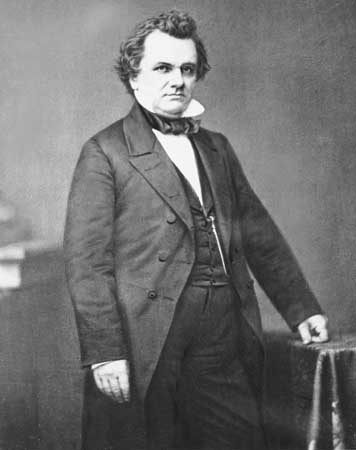

MR.

LADIES AND

GENTLEMEN: I

had supposed that we assembled here to-day for the purpose

of a joint discussion between Mr. Lincoln and myself, upon

the political questions that now agitate the whole country. The rule of such discussions is,

that the opening speaker shall touch upon all the points he

intends to discuss, in order that his opponent, in reply,

shall have the opportunity of answering them.

Let me ask you what questions of public policy,

relating to the welfare of this State or the I

will now call your attention to the question which Mr.

Lincoln has occupied his entire time in discussing.

He spent his whole hour in retailing a charge made

by Senator Trumbull against me. The

circumstances

out of which that charge was manufactured, occurred prior to

the last Presidential election, over two years ago.

If the charge was true, why did not “Now, fellow-citizens, I make the distinct charge, that there was a preconcerted arrangement and plot entered into by the very men who now claim credit for opposing a Constitution formed and put in force without giving the people any opportunity to pass upon it. This, my friends, is a serious charge, but I charge it to-night that the very men who traverse the country under banners proclaiming popular sovereignty, by design concocted a bill on purpose to force a Constitution upon that people.” In

answer to some one in the crowd, who asked him a question, “And you want to satisfy yourself that he was in the plot to force a Constitution upon that people? I will satisfy you. I will cram the truth down any honest man’s throat until he cannot deny it. And to the man who does deny it, I will cram the lie down his throat till he shall cry enough. “It is preposterous—it is the most damnable effrontery that man ever put on, to conceal a scheme to defraud and cheat the people out of their rights and then claim credit for it.” That

is the polite language Senator Trumbull applied to me, his

colleague, when I was two hundred miles off.

Why did he not speak out as boldly in the Senate of

the I am not going to allow them to waste much of my time with these personal matters. I have lived in this State twenty-five years, most of that time have been in public life, and my record is open to you all. If that record is not enough to vindicate me from these petty, malicious assaults, I despise ever to be elected to office by slandering my opponents and traducing other men. Mr. Lincoln asks you to elect him to the United States Senate to-day solely because he and Trumbull can slander me. Has he given any other reason? Has he avowed what he was desirous to do in Congress on any one question? He desires to ride into office, not upon his own merits, not upon the merits and soundness of his principles, but upon his success in fastening a stale old slander upon me. I

wish you to bear in mind that up to the time of the

introduction of the Toombs bill, and after its introduction,

there had never been an act of Congress for the admission of

a new State which contained a clause requiring its

Constitution to be submitted to the people.

The general rule made the law silent on the

subject, taking it for granted that the people would demand

and compel a popular vote on the ratification of their

Constitution. Such was the

general rule under Washington, Jefferson, Madison, Now, I will read from the report by me as Chairman of the Committee on Territories at the time I reported back the Toombs substitute to the Senate. It contained several things which I had voted against in committee, but had been overruled by a majority of the members, and it was my duty as chairman of the committee to report the bill back as it was agreed upon by them. The main point upon which I had been overruled was the question of population. In my report accompanying the Toombs bill, I said: “In the opinion of your Committee, whenever a Constitution shall be formed in any Territory, preparatory to its admission into the Union as a State, justice, the genius of our institutions, the whole theory of our republican system, imperatively demand that the voice of the people shall be fairly expressed, and their will embodied in that fundamental law, without fraud, or violence, or intimidation, or any other improper or unlawful influence, and subject to no other restrictions than those imposed by the Constitution of the United States.” There you find that we took it for granted that the Constitution was to be submitted to the people, whether the bill was silent on the subject or not. Suppose I had reported it so, following the example of Washington, Adams, Jefferson, Madison, Monroe, Adams, Jackson, Van Buren, Harrison, Tyler, Polk, Taylor, Fillmore, and Pierce, would that fact have been evidence of a conspiracy to force a Constitution upon the people of Kansas against their will? If the charge which Mr. Lincoln makes be true against me, it is true against Zachary Taylor, Millard Fillmore, and every Whig President, as well as every Democratic President, and against Henry Clay, who, in the Senate or House, for forty years advocated bills similar to the one I reported, no one of them containing a clause compelling the submission of the Constitution to the people. Are Mr. Lincoln and Mr. Trumbull prepared to charge upon all those eminent men from the beginning of the Government down to the present day, that the absence of a provision compelling submission, in the various bills passed by them, authorizing the people of Territories to form State Constitutions, is evidence of a corrupt design on their part to force a Constitution upon an unwilling people? I

ask you to reflect on these things, for I tell you that

there is a conspiracy to carry this election for the Black

Republicans by slander, and not by fair means.

Mr. Lincoln’s speech this day is conclusive

evidence of the fact. He has

devoted his entire time to an issue between Mr. Trumbull and

myself, and has not uttered a word about the politics of the

day. Are you going to elect Mr.

Trumbull’s colleague upon an issue between Mr. Trumbull and

me? I thought I was running

against Abraham Lincoln, that he claimed to be my opponent,

had challenged me to a discussion of the public questions of

the day with him, and was discussing these questions with

me; but it turns out that his only hope is to ride into

office on Trumbull’s back, who will carry him by falsehood. Permit

me to pursue this subject a little further. An

examination of the record proves that “And

until the complete execution of this act, no other election

shall be held in said Territory.” Now,

I will show you that when “There is nothing said in this bill, so far as I have discovered, about submitting the Constitution, which is to be formed, to the people for their sanction or rejection. Perhaps the Convention will have the right to submit it, if it should think proper, but it is certainly not compelled to do so according to the provisions of the bill.” Thus

you see that “Mr. Douglas—I have an amendment to offer from the Committee on Territories. On page 8, section 11, strike out the words ‘until the complete execution of this act, no other election shall be held in said Territory,’ and insert the amendment which I hold in my hand.” You

see from this that I moved to strike out the very words that

“Mr. Douglas—I have another amendment to offer from the Committee, to follow the amendment which has been adopted. The bill reads now: ‘And until the complete execution of this act, no other election shall be held in said Territory.’ It has been suggested that it should be modified in this way: ‘And to avoid conflict in the complete execution of this act, all other elections in said Territory are hereby postponed until such time as said Convention shall appoint,’ so that they can appoint the day in the event that there should be a failure to come into the Union.” The

amendment was unanimously agreed to—clearly

and distinctly recognizing the right of the Convention to

order just as many elections as they saw proper in the

execution of the act. Trumbull

concealed in his Alton speech the fact that the clause he

quoted had been stricken out in my motion, and the other

fact that this other clause was put in the bill on my

motion, and made the false charge that I incorporated into

the bill a clause preventing submission, in the face of the

fact, that, on my motion, the bill was so amended before it

passed as to recognize in express words the right and duty

of submission. On

this record that I have produced before you, I repeat my

charge that I

will show you another charge made by Mr. Lincoln against me,

as an offset to his determination of willingness to take

back any thing that is incorrect, and to correct any false

statement he may have made. He

has several times charged that the Supreme Court, President

Pierce, President Buchanan, and myself, at the time I

introduced the Fellow-citizens, I came here for the purpose of discussing the leading political topics which now agitate the country. I have no charges to make against Mr. Lincoln, none against Mr. Trumbull, and none against any man who is a candidate, except in repelling their assaults upon me. If Mr. Lincoln is a man of bad character, I leave you to find it out; if his votes in the past are not satisfactory, I leave others to ascertain the fact; if his course on the Mexican war was not in accordance with your notions of patriotism and fidelity to our own country as against a public enemy, I leave you to ascertain the fact. I have no assaults to make upon him, except to trace his course on the questions that now divide the country and engross so much of the people’s attention. You

know that prior to 1854 this country was divided into two

great political parties, one the Whig, the other the

Democratic. I, as a Democrat

for twenty years prior to that time, had been in public

discussions in this State as an advocate of Democratic

principles, and I can appeal with confidence to every old

line Whig within the hearing of my voice to bear testimony

that during all that period I fought you Whigs like a man on

every question that separated the two parties.

I had the highest respect for Henry Clay as a

gallant party leader, as an eminent statesman, and as one of

the bright ornaments of this country; but I conscientiously

believed that the Democratic party was right on the

questions which separated the Democrats from the Whigs. The man does not live who can say

that I ever personally assailed Henry Clay or Daniel

Webster, or any one of the leaders of that great party,

whilst I combated with all my energy the measures they

advocated. What did we differ

about in those days? Did Whigs

and Democrats differ about this slavery question?

On the contrary, did we not, in 1850, unite to a

man in favor of that system of Compromise measures which Mr.

Clay introduced, Webster defended, Cass supported, and

Fillmore approved and made the law of the land by his

signature? While we agreed on

those Compromise measures, we differed about a bank, the

tariff, distribution, the specie circular, the sub-treasury,

and other questions of that description.

Now, let me ask you, which one of those questions

on which Whigs and Democrats then differed now remains to

divide the two great parties? Every

one of those questions which divided Whigs and Democrats has

passed away, the country has outgrown them, they have passed

into history. Hence it is

immaterial whether you were right or I was right on the

bank, the sub-treasury, and other questions, because they no

longer continue living issues. What,

then, has taken the place of those questions about which we

once differed? The slavery

question has now become the leading and controlling issue;

that question on which you and I agreed, on which the Whigs

and Democrats united, has now become the leading issue

between the National Democracy on the one side, and the

Republican or Abolition party on the other. Just

recollect for a moment the memorable contest of 1850, when

this country was agitated from its center to its

circumference by the slavery agitation.

All eyes in this nation were then turned to the three

great lights that survived the days of the Revolution. They looked to Clay, then in

retirement at Now,

let me ask, how is it that since that time so many of you

Whigs have wandered from the true path marked out by Clay

and carried out broad and wide by the great Webster?

How is it that so many old line Democrats have

abandoned the old faith of their party, and joined with

Abolitionism and Freesoilism to overturn the platform of the

old Democrats, and the platform of the old Whigs?

You cannot deny that since 1854 there has been a

great revolution on this one question.

How has it been brought about? I

answer, that no sooner was the sod grown green over he grave

of the immortal Clay, no sooner was the rose planted on the

tomb of the god-like Webster, than many of the leaders of

the Whig party, such as Seward, of New York, and his

followers, led off and attempted to abolitionize the Whig

party, and transfer all your old Whigs, bound hand and foot,

into the Abolition camp. Seizing

hold

of the temporary excitement produced in this country by the

introduction of the Nebraska bill, the disappointed

politicians in the Democratic party united with the

disappointed politicians in the Whig party, and endeavored

to form a new party composed of all the Abolitionists, of

abolitionized Democrats and abolitionized Whigs, banded

together in an Abolition platform. And

who led that crusade against National principles in this

State? I answer, Abraham

Lincoln on behalf of the Whigs, and Lyman Trumbull on behalf

of the Democrats, formed a scheme by which they would

abolitionize the two great parties in this State on

condition that Lincoln should be sent to the United States

Senate in place of General Shields, and that Trumbull should

go to Congress from the Belleville District, until I would

be accommodating enough either to die or resign for his

benefit, and then he was to go to the Senate in my place. You all remember that during the

year 1854, these two worthy gentlemen, Mr. Lincoln and Mr.

Trumbull, one an old line Whig and the other an old line

Democrat, were hunting in partnership to elect a Legislature

against the Democratic party. I

canvassed the State that year from the time I returned home

until the election came off, and spoke in every county that

I could reach during that period. In

the northern part of the State I found Lincoln’s ally, in

the person of FRED DOUGLASS, the negro,

preaching Abolition doctrines, while Lincoln was discussing

the same principles down here, and Trumbull, a little

farther down, was advocating the election of members to the

Legislature who would act in concert with Lincoln’s and Fred

Douglass’s friends. I witnessed

an effort made at “The

Whigs, Abolitionists, Know Nothings, and renegade Democrats,

made a solemn compact for the purpose of carrying this State

against the Democracy on this plan: 1st.

That they would all combine and elect Mr. Trumbull

to Congress, and thereby carry his district for the

Legislature, in order to throw all the strength that could

be obtained into that body against the Democrats.

2d. That when the

Legislature should meet, the officers of that body, such as

speaker, clerks, door-keepers, etc., would be given to the

Abolitionists; and 3d. That the

Whigs were to have the United States Senator. That,

accordingly, in good faith And

now I will explain to you what has been a mystery all over

the State and Union, the reason why

A

meeting of the Free Democracy will take place at

September 9, 1858. THE FREE DEMOCRACY. Did

you ever before hear of this new party called the “Free

Democracy?” What object have these Black Republicans in changing their name in every county? They have one name in the north, another in the center, and another in the South. When I used to practice law before my distinguished judicial friend, whom I recognize in the crowd before me, if a man was charged with horse-stealing and the proof showed that he went by one name in Stephenson county, another in Sangamon, a third in Monroe, and a fourth in Randolph, we thought that the fact of his changing his name so often to avoid detection, was pretty strong evidence of his guilt. I would like to know why it is that this great Freesoil Abolition party is not willing to avow the same name in all parts of the State? If this party believes that its course is just, why does it not avow the same principles in the North, and in the South, in the East and in the West, wherever the American flag waves over American soil? Mr.

Douglas—Sir if you will get a copy of the paper published at

Waukegan, fifty miles from Chicago, which advocates the

election of Mr. Lincoln, and has his name flying at its

mast-head, you will find that it declares that “this paper

is devoted to the cause” of Black

Republicanism. I had a

copy of it and intended to bring it down here into Egypt to

let you see what name the party rallied under up in the

northern part of the State, and to convince you that their

principles are as different in the two sections of the State

as is their name. I am sorry

that I have mislaid it and have not got it here.

Their principles in the north are jet-black, in the

center they are in color a decent mulatto, and in lower

Egypt they are almost white. Why,

I

admired many of the white sentiments contained in I

am told that I have but eight minutes more.

I would like to talk to you an hour and a half

longer, but I will make the best use I can of the remaining

eight minutes. Mr. Lincoln said

in his first remarks that he was not in favor of the social

and political equality of the negro with the white man. Every where up north he has

declared that he was not in favor of the social and

political equality of the negro, but he would not say

whether or not he was opposed to negroes voting and negro

citizenship. I want to know

whether he is for or against negro citizenship?

He declared his utter opposition to the Dred Scott

decision, and advanced as a reason that the court had

decided that it was not possible for a negro to be a citizen

under the Constitution of the “I

should like to know if, taking this old Declaration of

Independence, which declares that all men are equal upon

principle, and making exceptions to it, where will it stop?

If one man says it does not mean

a negro, why may not another say it does not mean some other

man? If that declaration is not

the truth, let us get the statute book in which we find it

and bear it out.” Lincoln

maintains there that the Declaration of Independence asserts

that the negro is equal to the white man, and that under

Divine law, and if he believes so it was rational for him to

advocate negro citizenship, which, when allowed, puts the

negro on an equality under the law. I

say to you in all frankness, gentlemen, that in my opinion a

negro is not a citizen, cannot be, and ought not to be,

under the Constitution of the My

friends, I am sorry that I have not time to pursue this

argument further, as I might have done but for the fact that

Mr. Lincoln compelled me to occupy a portion of my time in

repelling those gross slanders and falsehoods that

MR. LINCOLN'S REPLY. FELLOW-CITIZENS: It follows as a matter of course that a half-hour answer to a speech of an hour and a half can be but a very hurried one. I shall only be able to touch upon a few of the points suggested by Judge Douglas, and give them a brief attention, while I shall have to totally omit others for the want of time. Judge

Douglas has said to you that he has not been able to get

from me an answer to the question whether I am in favor of

negro citizenship. So far as I

know, the Judge never asked me the question before.

He shall have no occasion to ever ask it again, for

I tell him very frankly that I am not in favor of negro

citizenship. This furnishes me

an occasion for saying a few words upon the subject.

I mentioned in a certain speech of mine which has

been printed, that the Supreme Court had decided that a

negro could not possibly be made a citizen, and without

saying what was my ground of complaint in regard to that, or

whether I had any ground of complaint, Judge Douglas has

from that thing manufactured nearly every thing that he ever

says about my disposition to produce an equality between the

negroes and the white people. If

any one will read my speech, he will find I mentioned that

as one of the points decided in the course of the Supreme

Court opinions, but I did not state what objection I had to

it. But Judge Douglas tells the

people what my objection was when I did not tell them

myself. Now my opinion is that

the different States have the power to make a negro a

citizen under the Constitution of the Judge

Douglas has told me that he heard my speeches north and my

speeches south—that he had heard me at Ottawa and at

Freeport in the north, and recently at Jonesboro in the

south, and there was a very different cast of sentiment in

the speeches made at the different points.

I will not charge upon Judge Douglas that he

willfully misrepresents me, but I call upon every

fair-minded man to take these speeches and read them, and

I dare him to point out any difference between my speeches

north and south. While I

am here perhaps I ought to say a word, if I have the time,

in regard to the latter portion of the Judge’s speech, which

was a sort of declamation in reference to my having said I

entertained the belief that this Government would not

endure, half slave and half free. I

have said so, and I did not say it without what seemed to me

to be good reasons. It perhaps

would require more time than I have now to set forth these

reasons in detail; but let me ask you a few questions. Have we ever had any peace on this

slavery question? When are we

to have peace upon it if it is kept in the position it now

occupies? How are we ever to

have peace upon it? That is an

important question. To be sure,

if we will all stop and allow Judge Douglas and his friends

to march on in their present career until they plant the

institution all over the nation, here and wherever else our

flag waves, and we acquiesce in it, there will be peace. But let me ask Judge Douglas how

he is going to get the people to do that?

They have been wrangling over this question for at

least forty years. This was the

cause of the agitation resulting in the Missouri

Compromise—this produced the troubles at the annexation of The other way is for us to surrender and let Judge Douglas and his friends have their way and plant slavery over all the States—cease speaking of it as in any way a wrong—regard slavery as one of the common matters of property, and speak of negroes as we do of our horses and cattle. But while it drives on in its state of progress as it is now driving, and as it has driven for the last five years, I have ventured the opinion, and I say to-day, that we will have no end to the slavery agitation until it takes one turn or the other. I do not mean that when it takes a turn toward ultimate extinction it will be in a day, nor in a year, nor in two years. I do not suppose that in the most peaceful way ultimate extinction would occur in less than a hundred years at least; but that it will occur in the best way for both races, in God’s own good time, I have no doubt. But, my friends, I have used up more of my time than I intended on this point. Now,

in regard to this matter about Trumbull and myself having

made a bargain to sell out the entire Whig and Democratic

parties in 1854—Judge Douglas brings forward no evidence to

sustain his charge, except the speech Matheny is said to

have made in 1856, in which he told a cock-and-bull story of

that sort, upon the same moral principles that Judge Douglas

tells it here to-day. This is

the simple truth. I do not care

greatly for the story, but this is the truth of it, and I

have twice told Judge Douglas to his face, that from

beginning to end there is not one word of truth in it. I have called upon him for the

proof, and he does not at all meet me as Mr. James Brown (Douglas Post Master)—“What does Ford’s History say about him?” Mr.

Judge Douglas complains, at considerable length, about a disposition on the part of Trumbull and myself to attack him personally. I want to attend to that suggestion a moment. I don’t want to be unjustly accused of dealing illiberally or unfairly with an adversary, either in court, or in a political canvass, or any where else. I would despise myself if I supposed myself ready to deal less liberally with an adversary than I was willing to be treated myself. Judge Douglas, in a general way, without putting it in a direct shape, revives the old charge, against me in reference to the Mexican war. He does not take the responsibility of putting it in a very definite form, but makes a general reference to it. That charge is more than ten years old. He complains of Trumbull and myself, because he says we bring charges against him one or two years old. He knows, too, that in regard to the Mexican war story, the more respectable papers of his own party throughout the State have been compelled to take it back and acknowledge that it was a lie. Here

Mr. I do not mean to do any thing with Mr. Ficklin, except to present his face and tell you that he personally knows it to be a lie! He was a member of Congress at the only time I was in Congress, and he [Ficklin] knows that whenever there was an attempt to procure a vote of mine which would indorse the origin and justice of the war, I refused to give such indorsement, and voted against it; but I never voted against the supplies for the army, and he knows, as well as Judge Douglas, that whenever a dollar was asked by way of compensation or otherwise, for the benefit of the soldiers, I gave all the votes that Ficklin or Douglas did, and perhaps more. Mr.

Ficklin—My friends, I wish to say this in reference to the

matter. Mr. Lincoln and myself

are just as good personal friends as Judge Douglas and

myself. In reference to this

Mexican war, my recollection is that when Ashmun’s

resolution [amendment] was offered by Mr. Ashmun of Mr.

The

Judge thinks it is altogether wrong that I should have dwelt

upon this charge of Having

done so, I ask the attention of this audience to the

question whether I have succeeded in sustaining the charge,

and whether Judge Douglas has at all succeeded in rebutting

it? You all heard me call upon

him to say which of these pieces of evidence

was a forgery? Does he

say that what I present here as a copy of the original

Toombs bill is a forgery? Does

he say that what I present as a copy of the bill reported by

himself is a forgery? Or what

is presented as a transcript from the Globe,

of the quotations from Bigler’s speech, is a forgery?

Does he say the quotations from his own speech are

forgeries? Does he say this

transcript from Now I would ask very special attention to the consideration of Judge Douglas’s speech at Jacksonville; and when you shall read his speech of to-day, I ask you to watch closely and see which of these pieces of testimony, every one of which he says is a forgery, he has shown to be such. Not one of them has he shown to be a forgery. Then I ask the original question, if each of the pieces of testimony is true, how is it possible that the whole is a falsehood? In

regard to Now,

I want to come back to my original question.

|